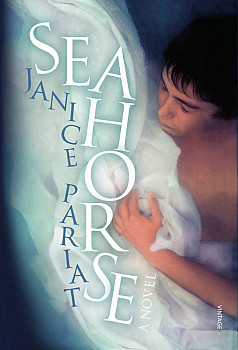

Preview and Review: Seahorse

The Read: Seahorse

Author: Janice Pariat

Publisher: Vintage Books, Random House India

Unravelling: A story about…well so many things. A coming-of-age tale about a literature student making his way through college, the journey towards finding a lost friend, new-age notions of love and romance, the overtones of homosexuality and bisexuality, and so much more. Inspired by the Greek myth of Poseidon and his male devotee Pelops, this book highlights the relationship between protagonist Nehemiah and art historian Nicholas; the latter almost playing Gatsby to Nem’s Carraway. Nicholas inspires wonderment and awe; it is so easy to get carried away by him. We are witness to Nem’s encounters with a variety of people (Myra playing a key role) through the story as also his journey from adolescence to being an adult.

She and Him: Nicholas, for obvious reasons. Mainly for exuding mystery and aura and being a man larger than life. We also loved Myra’s story. Her struggles, her passion, her desperation; we lapped it all up.

Quotable quote: There are so many moments across the narrative that stay with us. Our favourite, though:

‘What do you think it is?’ she asked. ‘The memory of happiness that has passed, is it happy or sad?’

The wine swirled full and viscous on my tongue.

Neither, I said. And both.

Memory only gives us back what we had on condition we know it has been lost.

To remake the world, we need first to understand it has ended.

What we loved: Seahorse comes with the baggage of being written by an excellent contemporary author, recipient of the Sahitya Akademi Award (Young Author) for her first book, Boats On Land. We loved how every aspect of it spoke of water. Be it the blue-green cover or the title font that flowed. Also, how the title flirts with the story. The seahorse, after all, is the only living organism whose reproductory functions are carried out by the male. The writing is impeccable and so poetic, which is not surprising considering Pariat describes herself as a poet first. Abstract in parts, it makes you tune out the world and focus on the story being told, which is told beautifully. The sexual deviances are written about with such simplicity and abandon that one wonders why they still baffle constitutions across the globe. There is an underlying theme of mysticism and enigma throughout the book. That’s probably why you’re left turning the pages to unravel all the whys and hows.

Maybe not: All the references to literature and art have to be researched by the reader, which can be enjoyable, but it can certainly not be classified as light reading. Needs thorough involvement.

Read it for: The poetry of the writing and the narration of a mythical tale in a contemporary setting. It will not disappoint.

An exclusive preview from Seahorse

Seahorses are strange creatures. Upright, they glide, rather than swim, moving with the current.

In lieu of scales, their skin stretches thinly over strong bony plates, intricately patterned in stripes, spots, swirls and speckles. Translucent yellow, electric green, liverish red, orange in love. They mate for long, if not for life.

Somewhere in China, they’re dried, and powered, dipped into soup, and whisky, believed to bestow everlasting virility and youth. They belong to that rarest of fish families marked by male pregnancy. And, most marvellous of all, they dance. A ritualistic courtship at dawn. They entwine their tails and float in unison, spinning gracefully through the water. They change colour. They dip, and rise, coordinated ballet partners in a routine long and exhaustive.

On several occasions, Nicholas and I tried to catch a glimpse of this—especially if we’d been drinking late into the night.

‘It’s four in the morning . . . shall we stay up for our piscine lovers?’

Although, maybe they were shy, or, as I offered, not really in love, for we never saw them dance.

‘It’s a myth.’ Perhaps they only danced in the sea. I’ve often wondered what happened to the pair in Nicholas’ aquarium. Whether he returned them to the resourceful shop owner in Chandni Chowk. If he gave them away to a fellow fish enthusiast in the city. And if he did, to whom? Whether they did or did not survive.

I could ask, I suppose, at the concert for which he’d sent me a ticket.

It was a fortnight away. And I still hadn’t decided whether I would attend.

Instead, I drifted. Around me, the London autumn slid into the beginning of winter.

The trees stood bare-branched and barren. Theatrical against the sky, all arms and fingers, reaching out in grief of epic proportion—Elektra mourning Agamemnon, Medea for Jason, Hecuba for Polydorus. And always the wind, the tragic wind.

I’d walk through Russell Square, marvelling at how different the park looked now, how the leaves had dropped overnight, extinguished, plastered wetly against the grass and paved paths. The lawns empty, the benches scattered with solitary figures, and, in the centre, the fountain bubbling in lonely regularity. My appointment as RLF Fellow kept me pleasantly occupied— although it was quite easy, really. For two days a week I was given a workspace, a small dusty room used by someone else on the other three, that also served as the site for the department’s abandoned file holders. Stashes of empty drawers lined the place, and I sat at the centre, behind a neat table, patient overseer of unused furniture.

‘It’s the best we could do,’ said Santanu apologetically, when he showed me the room.

‘But there’s this . . .’ I said, pointing to the window overlooking a small patch of garden, framed by a silver oak, leaves glistening in the rain. ‘Its perfect.’

In there, I met students, revised their assignments, and offered, for what it was worth, handbook advice on craft.

The ones who dropped by brimmed with questions, their faces marked by intent judiciousness. I marvelled at their devotion; I didn’t remember being as driven or committed as a student. Had things changed so much so quickly?

No. I stand corrected. It had been years since I left university.

On the weekends, I’d often meet up with Santanu or Eva, accompanied, sometimes, by Tamsin. They took me to places they thought I might enjoy—an open air play in Regent’s Park (rained out right after Olivia declared her unsought love for Cesario), a new tapas place in Islington (the prices as incendiary as the sangria), a walk through Highgate Cemetery (where, for the life of us, we couldn’t find Marx), and several art exhibitions. To the Tate, where we were utterly unmoved by Rothko, and the National Gallery, where we stood captured by Caravaggio. His Ragazzo morso da un ramarro. A painting of a youth—voluptuously androgynous—starting back in alarm as a lizard concealed in succulent cherries sank its teeth into his finger. His red, full lips pouting in pain, in pleasure.

One Saturday afternoon, Eva and I were strolling down Whitechapel Road after we’d been to see a show at the Whitechapel gallery—artwork by an immigrant British- Indian artist. Heralded, in the catalogue as an ‘extraordinary contemporary illusionist’, and we could see why. Smashed mirrors and perpetually spinning antique globes, a singing bowl, a rocking-horse unicorn, and tea cups in magically balanced towers.

‘Oh,’ said Eva, ‘Tamsin would like this.’ We were standing under a tree of faces. Made of fibreglass, with branches ending in waxy moulded heads of fantastical creatures. Manticores, winged bird-women harpies, crown-headed basilisks, a multitude of dragons, Japanese kappa, and seven-headed naga snakes.

‘And look,’ I pointed, ‘the Hindu bird-lion Sharabha . . . he looks ferocious . . .’

Eva giggled. ‘Also known as Santanu in a bad mood.’

Update: Transcriptions from the Twitter Chat with Janice

Q: Boats on Land and Seahorse are both closely knit to water. Why this connect with the aquatic life?

JP: Water is an element of transformation. My characters, both in BOL and Seahorse, undergo journeys that change them. Seahorse, as a retelling of the myth of Poseidon & Pelops, carries aquatic motifs echoing change & reflection.

Q: Nehemiah is quite an unusual name for a protagonist. Is there a story behind it?

JP: I trawl my friends’ friends lists on Facebook for unusual, interesting names! This sounded archaic & regal.

Q. Is any character inspired from real life? Till what extent?

JP: They tend to be concoctions, a feature stolen from here, a characteristic from there. Wrapped in fiction. There’s a Palestinian poet, Yara, who I based on a friend I adore…except she hopes to be a poet someday.

Q. What changed after a Sahitya Akademi award win to your name?

JP: It helped my writing career—but life hasn’t changed. Writing still frustrates & delights me. I’m still mostly broke!

Q. Which contemporary authors do you enjoy reading?

JP: Recently Donna Tartt, David Mitchell, Diriye Osman, Samanth Subramanian, Mira Jacob, Damon Galgut, among many.

Q. Do you have a writing ritual or a habit you have imbibed when penning down a story?

JP: I’m a terribly restless drifting writer. I pace & read my work out loud. But I mostly work in the mornings/afternoon. Also, I like to take a finished bit of writing with me to a cafe, and see if I can read it without being distracted.

Q. Both your books are riddled with mystery and mysticism. Which genre would you never take on?Which one are you waiting to try?

JP: I find that I first write something & then the ‘genre’ follows, so I don’t have any particular preclusions. Though I may possibly be rubbish at Science Fiction. I’d love to be commissioned a big fat travelogue. Doing something wild and wondrous. South America? This is obviously a hint.

Q. You describe yourself as a poet. Is there a book in the pipeline?

JP: My (small, slim) collection of poetry “A Memory of Place” should be out early next year…

Q. Do you have a characters story that stayed with you after the book?

JP: It would be Lenny’s. Because it’s the one that was most tragic & had most potential.

Q. Was it difficult writing the book from a male protagonist’s point of view?

JP: I found the sex scenes most difficult to write from Nem’s pov. Especially when he’s intimate with Nicholas.

Q. Any character you are partial to from Seahorse? Do you play favourites?

JP: I do play favourites. But my favourites keep changing. One day Eva. Another day it’s Nem. But mostly Myra.

Related posts from Verve:

Verve Trending

Sorry. No data so far.

us on Facebook to stay updated with the latest trends