Creating Spaces: Shweta Pai

The entrepreneur reflects on the personal experiences that pushed her to shape her niche passion project which is centred more around creating awareness than profit

Shweta Pai,

Muuyee, Founder

Bengaluru

I have always found it funny that when another adult finds out that I still buy children’s toys for myself they correct me and say, “Oh! You collect toys.” The suggestion is clear. If I’m an adult who isn’t buying toys for my own children, then I must have a niche intellectual or aesthetic interest in collecting them instead of simply being a grown-up who still likes to play. Shweta Pai is also one of those grown-ups. I bought my first Muuyee toy or ‘playmate’ in a concept store in Goa in 2018, the year Pai launched the brand. It is a beautifully crafted patchwork dung beetle naturally dyed in hues of indigo, yellow and earthy greens that now sits on the window seat of my bedroom overlooking the canopy of a mango tree. I clearly remember being drawn to it amongst the many products on display, particularly delighted by the fact that someone had thought to create a toy representing an insect most people would overlook, or worse, crush under their foot without a second thought. A dung beetle, of all things! It felt like a stranger had just validated my love for the Earth and its creatures through their design, in the last place I would imagine to seek it.

I immediately reached out to her and we have been in touch on-and-off over the last six years, connecting as fellow designers and resonating with each other’s work. Whether it is marvelling at the pom-pom shaped flowers of a powder puff tree over emoji-filled text messages, animatedly describing the potential of a large box of textile scraps over drinks at The Bombay Canteen, or telling me about all the “purely naughty stuff” from her childhood that she hopes to write about in her next storybook project in our interview, her deep commitment to play has been evident in every interaction we have had so far. Not many parents are excited about stories that get kids out of bed instead of into bed!

But when it comes to considering the making and end-of-life of every product she launches, Pai is very serious about the materials she uses, the processes she adopts, and the way she treats and compensates every artisan that brings her designs to life, and that comes at a fairly high price. Each Muuyee product is an invitation to invest in a more sustainable future for children. It sparks joy not only because of how it looks or the story it tells, but also how it is made. Pai regularly gets requests from customers to make clothes for “not so small humans” or host more art and craft workshops in parks, and it comes as no surprise that in the face of a climate crisis there is a growing community of people who are looking to connect with their inner childhood in the hope for a deeper connection to the natural world.

Creating Spaces is a series where Verve spotlights women working on community-driven creative projects across realms — food, sports, healthcare, parenthood, art, design and fashion. Each one has created a unique space, be it virtual or physical, while also challenging institutions and changing mindsets.

Through exclusive interviews and shoots, we delve into the motives that drive these women, their reflections on the influence their work has on their communities, and how their practices address the larger challenges facing urban Indian society.

Excerpts from the interview with Shweta Pai…

How did you discover your interest in art and design?

Till I was about eight to ten years of age, I would mimic my elder brother and spend my time playing outdoors, climbing trees and cycling. But the one thing that I recall being unique to me is that I was very attached to my stationary box. I loved sketching. My grandfather would indulge me and I even remember a very small steel scissor that he gave me from his shaving kit because I enjoyed cutting paper; I used to love trying new forms of arts and crafts as a child.

As I grew up, I was drawn to upcycling thanks to my mother. There is one cushion I fondly remember. It had mirrors and beautiful embroideries from Gujarat. And one day, I suddenly saw that she had turned this cushion into a sleeve for her sari blouse. She had happily cut it up and given it a new life. In fact, she would always be atypical with her blouses. Usually, saris came with a piece of cloth to match it but my mother would always wear them with a contrasting blouse. And for me, that seemed unique. I was always fascinated by her ability to make things her own. She was a banker but I think she should have been a curator — because she had a wonderful eye for arts and crafts. She would often befriend local artists. I remember she fell in love with the work of this one muralist from Kerala, and collaborated with him on a collection of 12 terracotta tiles for our house.

Take us through your journey of building a career in design.

I opted to study business management after high school — because as a teenager, I was influenced by my elder brother — and my first job was at a bank. Six months into it, I realised that it was not what I wanted to do. But I was on a very conventionally structured path and I did not know how to pivot. In the meantime, to keep myself occupied, I decided to redo my closet. I would visit local markets or the Khadi Bhandar in Bengaluru to look for textiles, take fabrics and patterns to the tailor, and ask him to stitch them for me. It soon became a full-time project. In fact, shortly after, I started consulting with Khadi Bhandar to help them merchandise their clothes and set up the space.

They invited me to attend a month-long all-India exhibition of khadi weavers organised by the Khadi and Village Industries Commission. On the first day, I saw that the products were showcased very plainly and did not do justice to how supple and wonderful these textiles were. The design language didn’t have much of an appeal. The exhibit was lacking when it came to offering innovative silhouettes or pairings. I had a bit of money at my disposal so I asked if I could produce a collection from the textiles that I liked out of the entire exhibit and display them. I made 12 garments and all the pieces sold out within half a day of that event. That gave me a lot of courage. That 12 became 25 garments, 25 became 50, and by the end of the month we ended up selling close to 500 pieces.

I applied for the Interest Subsidy Eligibility Certificate that enabled me to get an interest subsidy on a loan, employ a few people under me, and set up a small-scale business called Indiyarn. But I was still learning new skills — from tailoring and ironing to embroideries, I was fully immersed in the process. I ended up supplying khadi apparel to large retail players like Fabindia and Khadi Bhandar for a couple of years. Then came a point when I felt that the essence of what I had set up was getting diluted. It became all about solving quantitative problems rather than qualitative ones which began to feel like a race towards producing more and more. I realised that I wanted to study further. And I wanted to interact with like-minded people. I landed up at Srishti Manipal Institute of Art, Design and Technology in Bengaluru, and that is where my real education began. I realised that I am very multidisciplinary in my approach to design. I had tasted complete creative freedom there and could no longer be married to a single material or discipline. I graduated with a bachelor’s degree in textile design.

How did you find your niche in designing for children?

There was a series of experiences that not only sparked but also developed my interest in this field. While I was at Srishti, I discovered that I was drawn to how a child would perceive a concept or a story that I am trying to tell. How would they react to a particular visual outcome? I worked on an illustration project with Pratham Books. After that, I attended a workshop with a facilitator from Scandinavia; it was called Toy Lab and we had absolutely no restrictions on the kind of materials we could use or the concepts we could come up with. It was a perfect space for me to really bring my ideas to life. I also interned with a Bengaluru-based slow fashion brand called Smallshop for my graduation project. They were setting up a label called Small Story for children and I worked on their debut collection of toys and clothes. An exchange programme at The School of Design and Crafts at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden exposed me to sustainable textiles and natural dyes, and I became very interested in how they intersect with design for children. After I graduated, I worked with Khamir – a not-for-profit platform championing the traditional crafts of the Kutch region of Gujarat — to develop toys for their in-house brand.

How did motherhood shape the lens through which you look at childhood and play?

I became a mother soon after I graduated. In fact, I was pregnant with my first baby during my graduation. Her birth influenced many work-related ideas that were brewing in my head. As a mother, there were choices that I had to make and questions that I had to answer for myself and for this new life that I had created. How do I want to clothe this baby? What kinds of toys should I be introducing to my baby? What materials do I want her to touch?

The exchange programme in Sweden gave me a new perspective on how things were made. I was awestruck by the fact that I could create such gorgeous colours from my kitchen scraps. The peels of my onion, which are usually tossed without a second thought, produce such a vibrant yellow. The avocado seeds, which I collected over many days, gave me shades of mauve and pink. This knowledge influenced me at a very deep level and came back to me when I entered motherhood. I wanted to be very mindful about how I’m raising my child.

I was disappointed with the industrially-made products that were available for children in the market and recognised the potential for designing products that are produced more mindfully. Filling that gap was the intention with which Muuyee was born. When I walked into the big toy stores, I remember seeing toys made out of plastic. Most of the store displays perpetuated very clear gender stereotypes. The section for boys would be blue while the section for girls would be pink. It seemed like these stores were already deciding so much for the children even before they could make up their minds about who they want to be. It didn’t sit well with me. It pushed me to create a meaningful project, not just with the goal of creating for children, but to bring artisanal craft to this space.

In a market saturated with Western icons like teddy bears or Barbie dolls and toys that are made out of plastic, you look towards the natural world to inspire your production processes, both in terms of materials and iconography. What are the underlying values you hope to share with children through these choices?

“Muuyee” means “ant” in Konkani. An ant is such a tiny warrior. But when a colony of ants come together, their power is phenomenal. That idea of a community is so powerful to me. We need to cultivate a collective mindset that appreciates every living creature and values its health in the ecosystem. It is more meaningful when more people think alike…when parents, for example, choose something that is thoughtfully created, rather than pick a typical teddy bear made of synthetic fur or possibly carcinogenic materials that your child is liable to put into their mouth. And it’s also about being sensitive to the fact that once the child is done with the toy, it is not going to biodegrade. It is going to be around forever.

Compared to the more minimal kind of a childhood that I experienced — where everything was repurposed and we played for a longer time with very few things — relatively privileged children of this generation are born into excessiveness. We’re living in a cluttered world. And, often, we are so caught up in this consumerist culture that children don’t learn about the value of spending real time with loved ones. Through Muuyee, I just wanted to reinforce the importance of a less materialistic childhood for children.

You host a variety of hands-on workshops for parents and children in public spaces like parks. Tell us about the community you have cultivated through such events.

The workshops allowed me to bring people together and share the excitement that I felt about natural colours and well-made toys with them. I wanted to show them how our waste can have a meaningful afterlife. Why can’t a simple form lead to a toy? Why can’t children come together and make their own toys? That can be a form of play in itself. So we conducted a toy-making workshop and another one that was focused on natural dyes. Next, we organised an art workshop where we conveyed the importance of appreciating children’s not-so-straight lines and splatters.

The workshops created opportunities for interested parties to spend time in nature and talk about shared beliefs, and also for people to discover Muuyee because it’s a very niche brand. Mainstream global toy brands have flooded the markets although they manufacture their products in India, Bangladesh or China. But I don’t see them adding any value to children’s play spaces. Brands like Muuyee have to work very hard to educate buyers about why we exist and what we offer. It’s very easy for a brand like ours to perish because other brands operate at such a large scale. Their volume and presence are so flamboyant that brands like ours cannot compete in a numbers-led business model because they have the funds to aggressively market their products to children.

We just shot our latest collection, and except for two of the children, the others had never worn Muuyee. One child was wearing a pair of undyed embroidered pants from our new collection and he was so comfortable in them that he didn’t want to take them off even after the photo shoot was over. I handed down a pair of shorts and a crop top that my daughter wore for three years to a friend whose child now calls it her favourite. It is reassuring to me that children are enjoying natural colours and undyed fabrics because it lets their skin breathe. These are all handloom textiles that absorb sweat, and because children are always moving around, it suits the purpose. They prefer wearing these over synthetic clothes, which may trap heat and stick to their skin.

Tell us about the slow and sustainable practices and techniques that you ended up adopting….

Indian markets are still very price-sensitive. We also still value European and American brands more than local brands. It is one of the reasons why I have been intentional about Muuyee products not giving an ethnic vibe. I don’t want the customer to just associate the clothes with festivals, for instance. The brand has adopted Japanese concepts of sewing and we wanted to be as gender-neutral as possible. These practices have lent the brand a global feel. This is not to say that all our clothes are made in unisex silhouettes; we make dresses along with unisex clothing like shirts and rompers. We produce in small batches, and therefore the artisans charge a higher price. Actually, even if it’s a bigger batch, artisans have to be paid fairly. But the economics of small-batch production is very different. We can’t take huge leaps because we are self-funded — our decisions to grow have to be thought through.

In terms of production, we start from scratch, and that’s with handloom or khadi fabric. The yarn is spun by hand and we ensure that our textiles come from handlooms. We only use natural dyes which are slow and sustainable because they are processed by hand and use zero-waste principles. Once the dyeing is complete, all the water used can be repurposed. It goes into farmlands or the nearby tea gardens for irrigation. We work with Srishti Trust in Munnar, Kerala, all the water gets repurposed for their tea plantations. This is particularly true in the case of indigo — the water actually helps the plants grow better. We also use dyes like myrobalan or madder. What we use comes from the earth, and we are able to send it back to earth, without any guilt. Then we make use of techniques of hand-embroidery. Although it’s more time-consuming, labour-intensive and expensive, these are crafts we need to uphold; otherwise, they will all fade away. There’s a lot of emphasis on quality, neatness of finish, and this is why all of our collections are still in production and relevant today.

Tell us about finding inspiration in India’s diversity of flora and fauna.

My interest in fauna developed during a trip to Periyar National Park and Wildlife Sanctuary in Kerala. We spent every morning walking in the jungle on beautiful guided tours and early morning birding trails. That’s when I came across a lot of interesting creatures that inhabit Indian forests but I hadn’t grown up learning about. I had played with a kangaroo in my childhood but never a lion-tailed macaque. Why is this animal not as celebrated? The Malabar whistling thrush, which has such an interesting behaviour of whistling like a human being, is a bird I had never heard of. Where were the references of monsoon purple frogs and the draco lizards that fly? Seven of these lesser-known — some of which are endangered creatures — inspired the My Darling Earth line of clothes or “wearables”, toys or “playmates”, and shibori textile artworks. Another collection of clothes called Noon Light came from a day spent at the park. We had spread our mats and were lying under the soft shadows that all the tree canopies had created. I wanted to celebrate this time of the day and that rested feeling you get from a peaceful afternoon slumber, and we managed to translate it beautifully using silk. Similarly, the colour white inspired Milky Way, and Blues & Beetles was inspired by the fascinating details of the insect world which I designed using indigo.

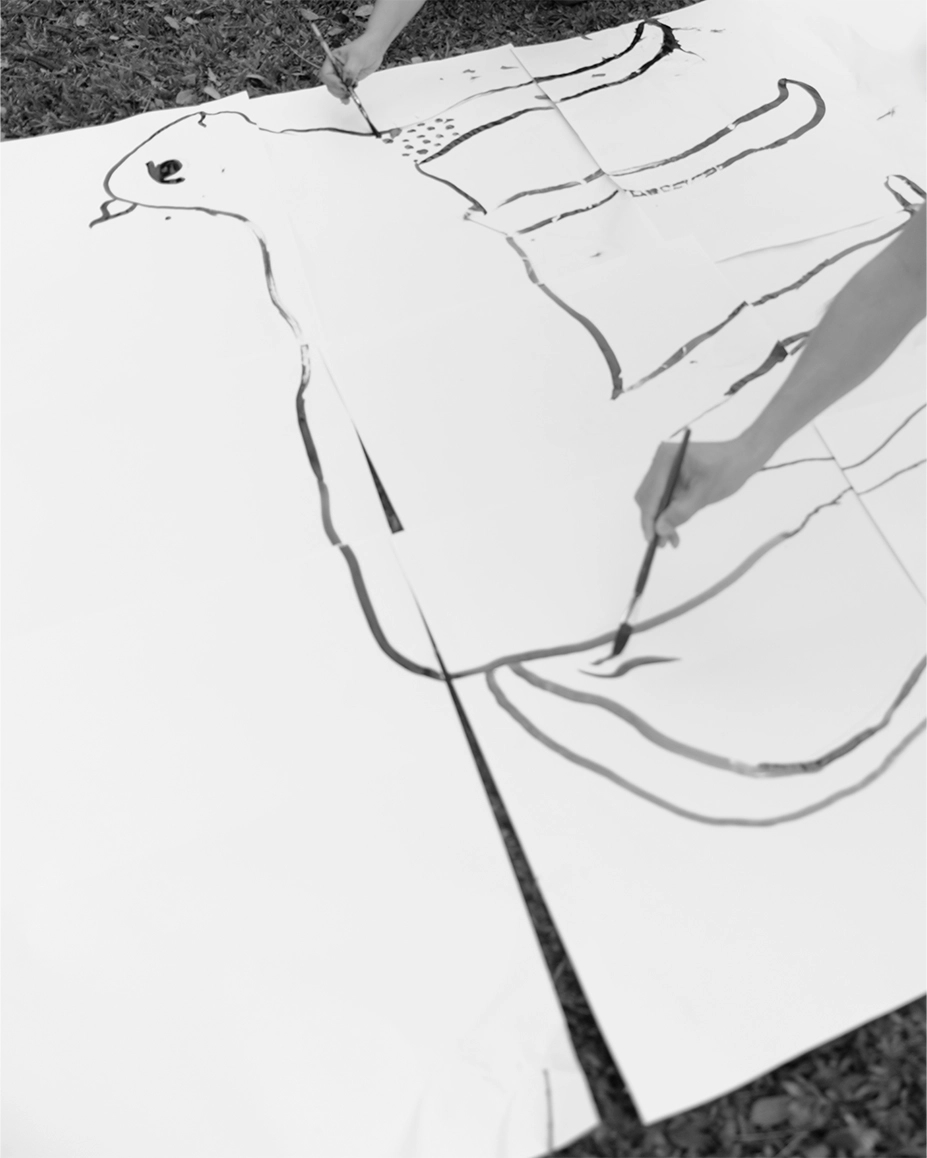

Even the designs of our upcoming collection Monkeying Around comes from my own encounter with a monkey during my design school days. When I would go out to sketch, I would see monkeys swinging from the trees. It struck me how childlike those monkeys were — from their body language to their naughty spirit! For the What Flew By? (Panchchi) range, I revisited my childhood desire to befriend birds — an association that is nostalgic to me even today. I specifically remember how I would approach them but every time I would move one step closer, they would move away. And I never thought that this childhood memory would resurface after so many years and get translated into vivid illustrations made out of pastels. I created a lot of artworks for the collection by layering strokes of pastel colours on paper, and then scratching and scraping back the layers in certain places, and these were beautifully interpreted by the artisans.

What is the process of creating a Muuyee product?

The process begins with the birth of an idea which is very organic and personal for me. Every idea is followed by a lot of sketching. Then we move into 3D prototyping either with clay or paper. Then it goes to the artisans and is reinterpreted by them. All our toy artisans are based in Kolkata, the dyers are in Kerala, and our tailors are in Bengaluru. The artisans look at the sketch and the prototypes and we discuss the creative process over phone calls. It’s a very collaborative process because they are the ones with an expert sense of the final possibilities. It isn’t just me telling them what to do, I like to get their inputs. They work on a second set of prototypes which are sometimes amazing at the get-go. At other times, they go through multiple iterations. But the artisans have also understood that this is how I work and I think they see value in it because once the design is sealed and we are convinced that it is a good design, we produce it for a very long time. And they get paid for any number of trials they are doing so they know that their work is going to be honoured and compensated for.

I’m currently working on a collection of clothing staples and experimenting with how collaborative I can be by playing with whatever the artisan is making or has surplus of at the time. This also means that I can sell these staples at a lower price than our special collections. We recently picked up some appliqué patches of animals from an artisan cluster in Barmer, Rajasthan, which are traditionally known as hathi-ghoda appliqués and I’m going to use them on khadi fabrics from Karnataka. Not creating textiles from scratch and instead using what is there and playing with it is adding to our sustainable practices. Sometimes, there are lots of scraps left over from different projects. We sort them into cool colours, neutrals and warm colours, and then create new textiles or explore surface treatments with them. That’s also something we have always enjoyed doing — playing with whatever is left. Monkeying Around and Round And Round use scraps as well.

Tell me about illustrating the handbound book Jungle Tails, with which Muuyee forayed into children’s publishing in 2021….

That book also came from my walks in the Periyar forest which are home to so many diverse creatures. Seeing them live freely in the wild gave me the idea for a book that talks about preserving their rights. We communicate how important it is that we give them space to enjoy their habitat peacefully. I imagined the characteristics of many of these creatures, along with their unique quirks and the vivid niches they occupy in the ecosystem. Printed on recycled paper, the book celebrates them and their right to live a full life in the forest. I collaborated with illustrator-writer Malvika Tewari, who designed the layout and wrote the poetry verses for it and through it we introduce readers to 10 endangered species, what they eat, which parts of the forests they occupy, and more — all with the hope of making children fall in love with our natural environment.

How does your 10-year-old daughter interact with your work? You often involve her in the design process and use her drawings and doodles.

She has a lot of love for what I create, because she’s been part of every bit of the journey — from my visits to artisans in their villages to making the designs with me. But I am observing a shift in her perception of what’s valuable now. Eight or nine is the age when children begin to want to belong. They cannot not know a popular character — say, Harry Potter. There is a lot of pressure that they feel when they go to school because they are entering a world where mainstream popular culture is celebrated. You might find two or three children in an average class who might have watched Studio Ghibli movies or developed a deep and vocal appreciation for nature. And I personally feel it’s okay for them to show a little bit of interest in trying to fit in with the others. As parents, it is important to lay a strong foundation of values and beliefs when children are young. One has to trust that these will stay with the child.

My child is going to stand out in Muuyee clothes while the others might be wearing popular brands, and she may not want that always. As a parent, it is important to not feel dejected when you put in the effort to encourage an alternative lifestyle and your children are not interested. At some point, my child will remember the difference between a handwoven textile and a synthetic material, for example. And, sometimes, they have to make wrong choices before they make the right ones, and we have to give them the room to go through that. On my part, I will always offer her the option of an alternative choice, and I do see my daughter choosing that at times.

How do you stay connected to your inner child?

Firstly, I think, innately, I am open to being vulnerable. If I feel like crying, I cry. If there's something that really moves me, I get as excited as a kid would. So, in some ways, I haven’t really perhaps grown up to become a conventional adult in terms of always reining in my emotions. It is very easy for me to think a little bit like a child. That helps me in connecting with kids very easily. I would happily choose to hang out with children over some adults. I connect with their lack of judgement, and enjoy being silly.

Secondly, after becoming a mother, the best thing that has happened is that I am able to recall my childhood memories by way of being a part of this child’s life. I have pulled out every story from my childhood and I tell them as bedtime stories. Bachoo — the collection we launched in October to celebrate the brand’s sixth anniversary — comes from imagining the world of a six-year-old girl who draws without boundaries — whether it is on her body, the walls and floors, or with the sand at the beach. And when she draws, there are no limits to what these drawings could be of — a cat with face paint, a bird flying with one wing, or a girl with twisted knees and twisted hands. I let my imagination go wild, made doodles and then used them to build a story.

For my next project, I really want to work on a bunch of stories from my childhood — the naughty stuff. These stories should be able to make a child want to get out of bed! If you’re designing for children, you need to really connect to your own childhood at a deep level. And that means being silly, intuitive and very forgiving. Children cry and get angry easily but they’re also fine very easily. They reconcile so fast. They just make up and they’re friends again. But, I think, as adults, we sometimes do not have that ability to move on. I think it’s why we keep fighting so many wars. So, that conscious decision to stay simple keeps me connected to my inner child.

At the links below read more from the Creating Spaces series:

Radha Lath Gupta, She Talks Ball, Founder

Shruti Taneja, Nivaala, Founder

Anchal Notani, Two Extra Lives, Founder

Payal Shah, Kobo Fermentary, Founder