Shruti Taneja,

Nivaala, Founder

Delhi

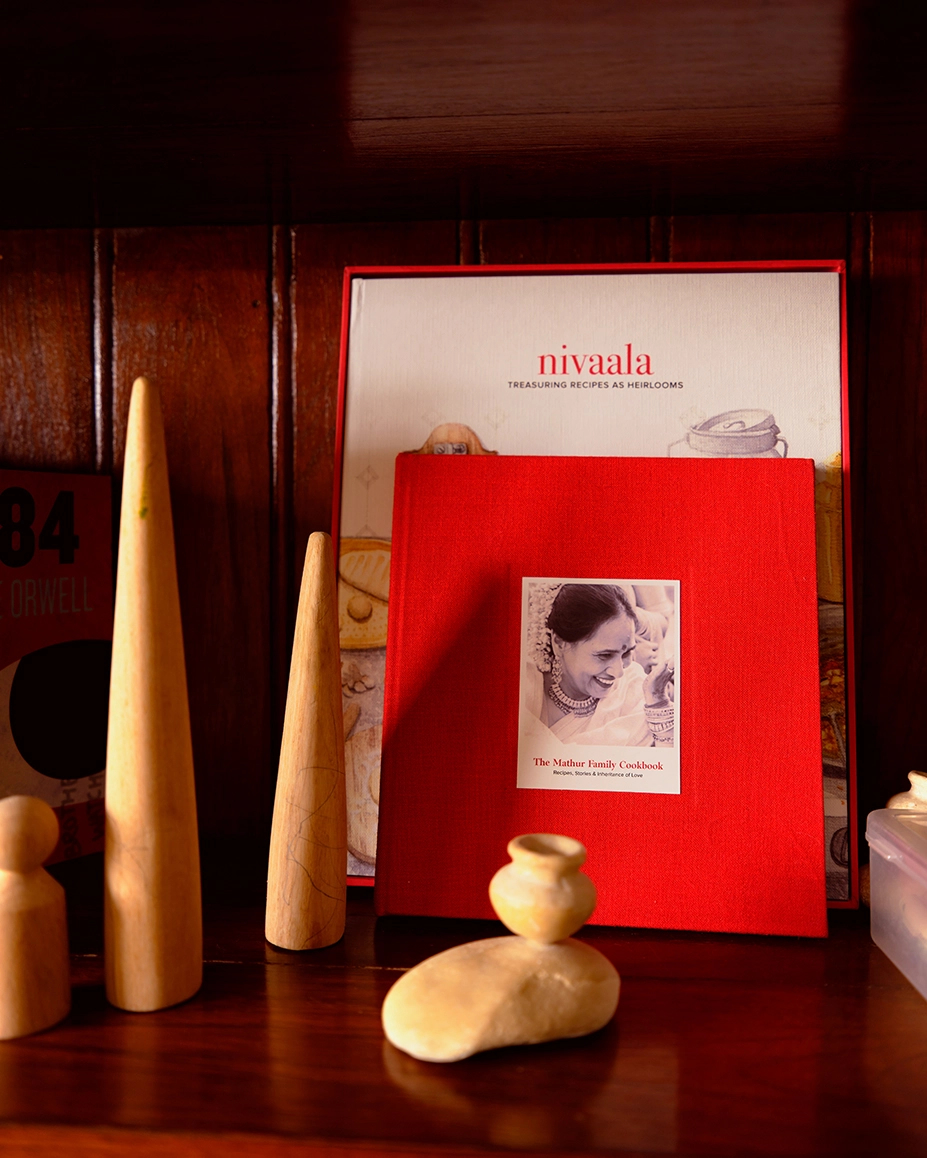

To interact with Shruti Taneja is to be struck by how consistently she embodies her message that “recipes are heirloom treasures”. Whether it is through her platform Nivaala — that serves up recipe journals, personalised cookbooks for families and ingredient-driven zines — or simply teaching her nephew to cook, she underscores the importance of preserving one’s family recipes.

Early on in our conversation, the 36-year-old reveals that she comes from a family of feeders and tells me about her family’s belief that cooking is passed down through our DNA. True to her genes, while I was coordinating logistics of the photo shoot with her, she was preoccupied with what she could arrange for the crew to eat, and whether they had any dietary restrictions or allergies, rather than picking out outfits. Thanks to her, I learnt that one of our team members is allergic to mustard.

The act of feeding people, and allowing loved ones to feed you in return, is a deeply personal matter to Taneja, and one that I can relate to — we have both lost mothers whose cooking we miss every day. But while I simply tucked away the few of my mother’s scribbled recipes that I could find — profiteroles being my most prized one — in a drawer, Taneja made it her life’s work to remind the rest of us to document family recipes before it is too late, with or without availing of Nivaala’s services.

Creating Spaces is a series where Verve spotlights women working on community-driven creative projects across the realms of food, sports, healthcare, parenthood, art, design and fashion. Each one has created a unique space, be it virtual or physical, while also challenging institutions and changing mindsets.

Through exclusive interviews and shoots, we delve into the motives that drive these women, their reflections on the influence their work has on their communities, and how their practices address the larger challenges facing urban Indian society.

Excerpts from the interview with Shruti Taneja…

Tell us about your relationship with food in your growing-up years. How has it evolved over time?

I grew up in Delhi and spent a fair bit of time in my nani’s house. Her door was always open to everyone and she could whip something up in the kitchen last-minute. She would regularly invite guests over for lunches and dinners, and talk about what to cook next. I was intrigued by the seasonal foods, pickles and aam panna she would prepare during summers as well as the fermented drink we call kanji [a North Indian probiotic drink traditionally made with spices, water, and either carrot or beetroot] during winters. This was a hobby I saw my mother take on as well. So I grew up around a strong passion for food, feeding and hosting. But I never really cooked. In my family we believe that cooking is passed down through genes. That if you come from a lineage of good cooks, you are likely to excel at it whenever you take it up. So she encouraged me to use my younger years to learn other skills — playing the violin and tennis, skating, swimming, to name a few.

My mother would find innovative ways to feed vegetables to me. Stuffing them inside parathas was her go-to solution. For example, she would mash peas with spices, or grind spinach and beetroot and combine it with the dough. In fact, any kind of stuffed paratha that you could imagine would be made at home — parathas would be made with black gram, potatoes, raw papaya even. The accompanying condiments were my favourite part. I still love a diversity of chutneys and achaar. It is my comfort food.

My elder brother started cooking before I did — when he went to Canada at the age of 18 for college. In 2002, in his second year, he’d email my mother for recipes. He used to cook for sustenance and survival so these were easy-to-cook dishes. I moved out for college early too. Western food held more appeal for me at the time, so I wanted to learn how to cook Italian and Mexican food with the help of easily available sauces. Indian food was something I ate only when I came back home during my breaks.

What was the motivation behind starting Nivaala?

In 2015, when my mother passed away, I found myself craving her dishes. All of us have those favourites that are specially made for us by a loved one — and when I couldn’t recreate them, I was struck by how we talk about inheriting material objects like jewellery and saris but don’t think of recipes and the art of cooking as an inheritance.

The idea for Nivaala came to me in the time between my mother’s demise and my nephew’s birth in 2019. I saw my brother’s son eating the food that his maternal grandmother was cooking and I felt sad that he would never get to eat the food that we grew up eating. I wanted to pass on some of my mother’s recipes and have him taste those, especially the laddoos she used to make. Food is an important marker of one’s identity and I wanted to share our food history with him.

Since I have started living alone, I have chosen to not hire a cook because I want to be able to make the food that I grew up eating. When I spend those two hours in the kitchen on Sundays to prep my meals for the week ahead, I try to figure out how to adapt our family recipes in a way that I know will comfort me.

What prompted you to shape Nivaala as a larger community project?

The more I spoke to my friends, whether married or single, the more I saw them going through similar dilemmas. And whether they are based abroad or here in India, most of them do not cook as well as their mothers did. They didn’t realise it until the pandemic years when I started the conversation about our parents’ mortality and how these recipes may get lost. People grow old, lose their memory…. More importantly, food can be a source of comfort during times of loss. With this thought in mind, I decided to do something on a larger scale and not just document my own family’s recipes.

When I was in New York in 2019, I came across recipe journals in shops but they were designed for Western ways of cooking. The field for “prep time”, for example. There would be a place for cocktails and starters. I would have liked something that allowed me to document memories and emotions attached to recipes instead of just the set courses. I saw a gap for a recipe journal that would mention elements like which generation a particular recipe came from, in addition to ingredients and instructions. So when I started Nivaala in 2020, as a passion project — I was a marketing professional at the time — my aim was to create a recipe journal that is more suited to a South Asian context. I taught myself the basics of graphic design and commissioned an illustrator. I went through many versions. It took me six months to create the final prototype.

What fuelled Nivaala after you created that first recipe journal?

All of my past work in marketing, whether it was in the beauty industry or the renewable energy space, involved collaborations with or facilitating collaborations between stakeholders. I’ve always believed it to be a powerful tool and I grew Nivaala in a similar way. I got lucky early on to be able to partner with Goya Journal — an open access, peer-reviewed, international journal focusing on heirloom recipes and culinary traditions from the Subcontinent — with whom I put together a digital cookbook with family recipes from eight reputed Indian chefs such as Manu Chandra, Thomas Zacharias, Pooja Dhingra and Kainaz Messman. We raised Rupees 12.3 lakhs through the sales within a span of two weeks and used the proceeds to provide meal kits to Mumbai slum residents affected by COVID-19. Simultaneously, I partnered with The Alipore Post, a weekly art and poetry newsletter, to facilitate recipe exchanges during lockdown, to usher in a sense of community during the difficult times we were collectively facing. I also met Chinmayee Manjunath, a books editor and publisher, and we bonded over the importance of documenting family recipes. Together, we started Andaaz Publishing, a publishing service aimed at helping families preserve their heirloom recipes and culinary histories, in 2023.

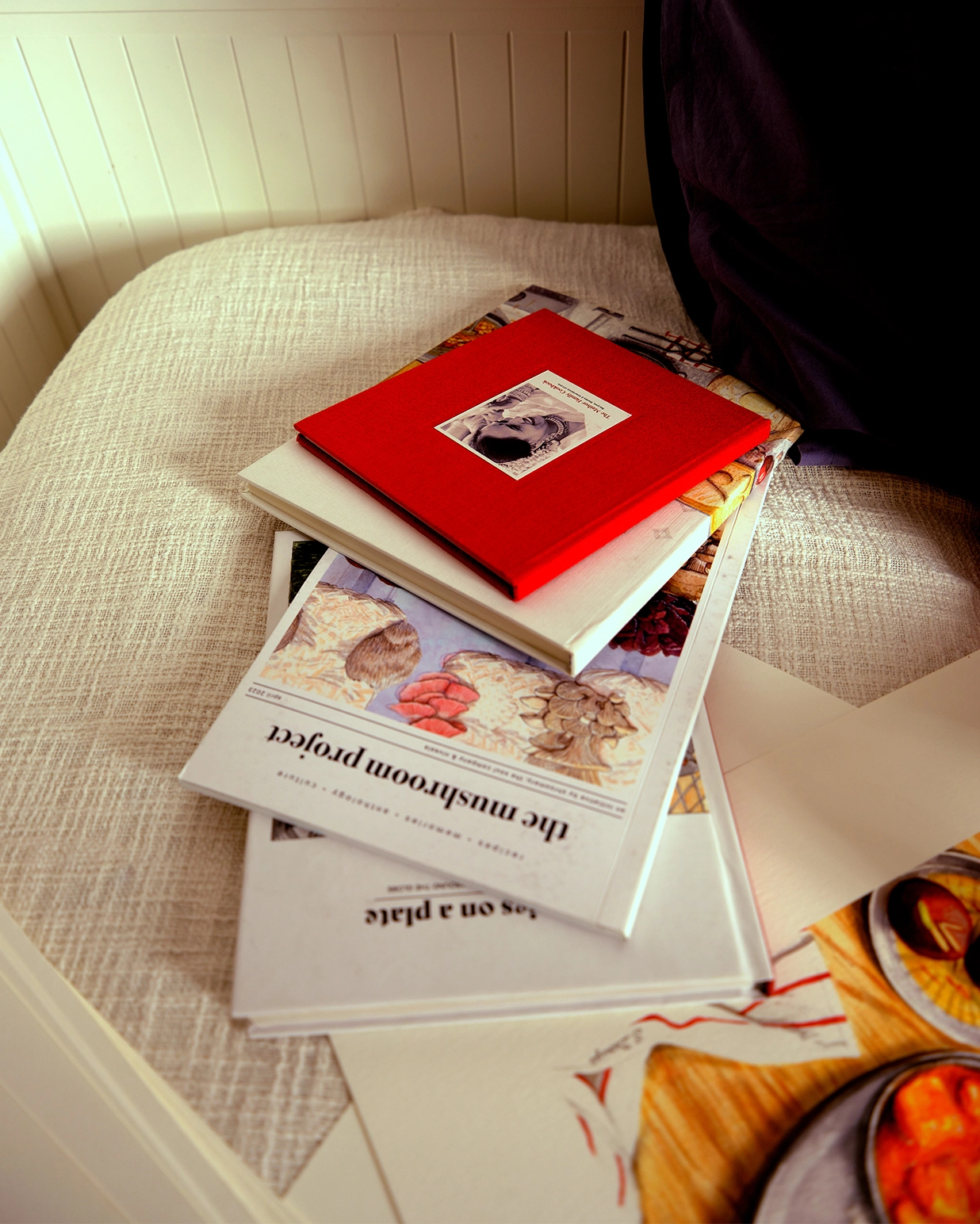

While working on the very first recipe journal, what struck me was the diversity of Indian food and ingredients, and how underrepresented it is, especially at an international level where dal makhani and butter chicken are still stand-ins. The reality is that our cuisine changes every hundred kilometres. Something as simple as a souring agent isn’t singular. Tamarind was the only souring agent I knew of but I realised that other regional communities use vinegars, anaar dana [a spice made from dried pomegranate seeds] and kokum, and the ingredient influences the flavour profile. So, I started working on a series of zines, each based on a single ingredient. We’d send each ingredient across to chefs and home cooks from around the country and ask them to share recipes to showcase how versatile Indian cooking is. We called the first zine The Legume Project and for this we sourced rajma from Tons Valley Shop in Uttarakhand. Then came The Mushroom Project in collaboration with Shroomery, a gourmet mushroom shop, and The Jackfruit Project with Eat With Better, a business that was shuttered in 2023. There’s much that needs to be documented. Eventually, I could see Nivaala take on multiple forms, be it recipe journals, cookbooks, zines or experiences, and I decided to work on it full-time.

What is the thread that ties all these different verticals together?

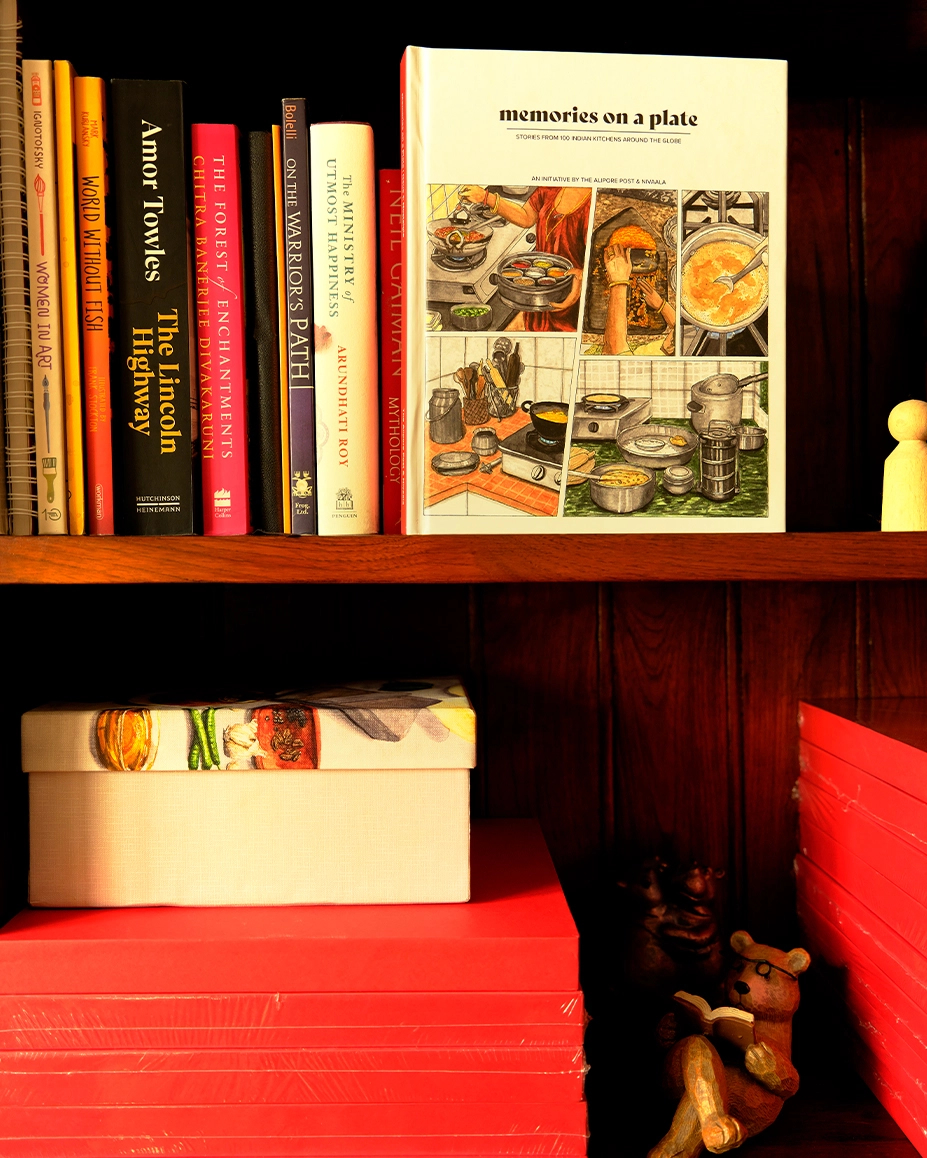

The belief that recipes are heirlooms and that we need to treat them as such. They’re meant to be passed down. One project has led to another. The ingredient-based zines led to another collaboration with Goya Journal called Kitchen of One’s Own, which was part-community cookbook containing over 40 recipes and part-recipe journal for customers to pen down their own recipes. The self-publishing vertical caters to the requests we were getting from families to create cookbooks as gifts. Through it, we try to make the process of documentation seamless and approachable and provide an end-to-end service that includes documenting, editing, designing and publishing. That gave way to Memories On A Plate, a crowdsourced multi-format anthology of stories of Indian kitchens that included poems, photo essays, long-form essays, comics and recipes. This was our second collaboration with The Alipore Post. Next, I am planning on publishing for children, having realised from reading to my nephew that there are very few children’s books referencing Indian food and cooking.

What made you identify print as your medium of choice?

When I was grieving my mother, I looked toward tangible objects to hold on to for comfort. The online experience is very different. I held onto letters and notes she had scribbled. In her last months, my mother was on a ventilator with a pipe through her throat and she couldn’t talk. She would write notes to communicate with us and I still have those. Written words by someone you love is of high emotional value and we often realise it after they’re gone which is why I chose to create the recipe journal as my first project.

We got into custom-printed cookbooks because our clients were looking to create a tangible document of their family recipes that they could share with relatives. When you’re cooking, it’s just nicer to have a book open, despite the stains, versus having your device open nearby. And at some point the stains become precious markers of a past time. Besides, owning something belonging to a lost loved one makes you feel closer to them. That being said, we are building a digital map of India where each region will have its heirloom recipes documented by local home cooks.

Tell us about the community that you have cultivated through this work.

Through our community, we’ve had the opportunity to document recipes belonging to a diversity of food cultures, from Kannadiga to Goan to Mumbai Christian families. Indian recipes are based on andaaz or estimation. And many struggle with figuring out how to provide measurements. We have encouraged our clients to switch on their voice recorders when asking elders to share recipes. We include these voice notes in the family cookbooks via QR codes.

The first customer who ordered my recipe journal — she is from Puducherry — emailed me two months after the purchase, asking to buy two more. She said she had finished filling the book with 40 recipes and now wanted her aunts to fill up the new books with their recipes and give them back to her. A lot of the sales have also come from customers living abroad. In my experience, diasporic communities are looking to stay rooted and they take their cuisine far less for granted.

In 2023, I launched a raw mango mustard or aam kasundi in collaboration with Chef Anuroopa Banerjee, who was working with Jaipur Modern: Store & Kitchen at the time. As part of the promotion, we went to her ancestral house in the Shekhawati region in Rajasthan and documented how it has been prepared by her family and captured some of the emotions attached to this condiment. It was very well received. Ironically, that condiment vertical had to be shut down because the demand was too high and we couldn’t keep up with production. But curating experiences and allowing my community to taste these recipes is definitely something I hope to revisit in the future because it is a very enjoyable process for me, personally.

Why are we rapidly losing these diverse ways of preparing food in a Subcontinent that has had great success in passing traditions down orally for so many generations?

The oral tradition is lost because our generation isn’t entering the kitchen as much. Women, who are part of the workforce, have time constraints. Men should participate as well.

And I do think that the shift will happen. A lot of our customers are men. They are buying the journals and partaking in the important effort to document their family’s food and culture. Boys are being raised differently. We’re teaching my nephew how to cook. We make ladoos and parathas together. It’s up to both the men and women of our generation to preserve the recipes. If we don’t, it won’t be long before we forget our heritage.

Recipes evolve with each generation and also the place you might be in or ingredients you have access to. It is not just about being nostalgic about the past but also carrying it with you into the present.

At the links below read more from the Creating Spaces series:

Radha Lath Gupta, She Talks Ball, Founder

Anchal Notani, Two Extra Lives, Founder

Shweta Pai, Muuyee, Founder

Payal Shah, Kobo Fermentary, Founder