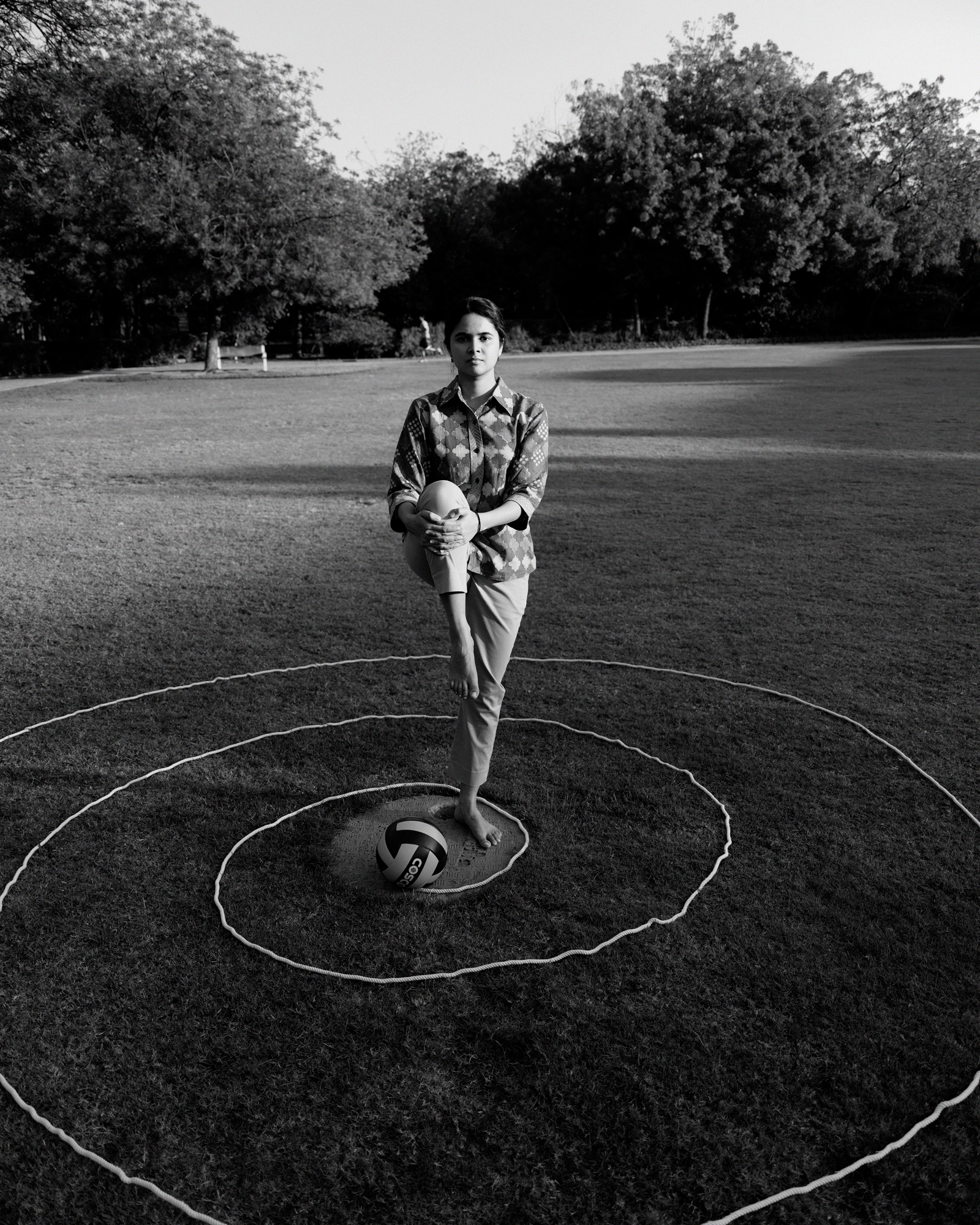

Radha Lath Gupta,

She Talks Ball, Founder

Ahmedabad

I discovered 24-year-old Ahmedabad-based Radha Lath Gupta’s platform She Talks Ball — a multiplatform initiative that focuses on women’s sports — during the first lockdown in 2020. Not because I happen to be passionate about sports but because of a personal connect — my cousin and she were teammates at the Ashoka University football team which was raising funds for vulnerable communities that were disproportionately affected by the ongoing pandemic, and I had signed up to be a sponsor.

Over the course of the next six weeks, I received timely updates on the number of kilometres they ran or cycled (4,319 kilometres in total) along with receipts of donations to various charitable organisations. In addition to the individual messages to each sponsor, it was their sisterhood that was inspiring to me and continued to be a theme during my interview with her.

Radha Lath Gupta is a girl’s girl. She found her footing within sports only after joining an all-girls team and she has discovered some of her closest friendships through it. Her coverage of women’s sports reflects this solidarity, marked as it is by how she cheers for and champions female athletes and sporting professionals.

Creating Spaces is a series where Verve spotlights women working on community-driven creative projects across realms — food, sports, healthcare, parenthood, art, design and fashion. Each one has created a unique space, be it virtual or physical, while also challenging institutions and changing mindsets.

Through exclusive interviews and shoots, we delve into the motives that drive these women, their reflections on the influence their work has on their communities, and how their practices address the larger challenges facing urban Indian society.

Excerpts from the interview with Radha Lath Gupta…

Tell us about your relationship with sports in your growing-up years.

When I was growing up in Mumbai, my parents prioritised living near a playground so playing outdoors was an integral part of my childhood. When I was eight years old, the school football coach suggested I attend practice. I declined initially, not wanting to commit to waking up at 6 a.m. but I was convinced when I learnt that it was an all-girls’ practice. I had only played with a mixed group until that point and since the majority of the team had been boys, they had always had their way when it came to selecting teams. Going for that 6-a.m. practice made me realise how much fun I had playing. I looked forward to it everyday, and it allowed me to find my footing within sport. Eventually, all of my girlfriends joined the school team. We’d play in the mornings and go to class late and tired. We won the under-12, under-14 and under-16 competitions for our school.

It is intrinsic to team sports that you become close to the people you play with because you have to bring out the best in and mutually support each other to ultimately win a game. At every institute I have been enrolled in — whether it was as an undergraduate at Ashoka University or even now at the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad (IIMA), where I am pursuing my MBA — I’ve found my closest friends through sport. A senior invited me to football practice in my first week at Ashoka University, and I invited a girl who in turn brought two more girls and we all became team members and friends. We practised for three hours every evening and then had dinner together. But then COVID-19 hit and broke our routine. To stay in touch and raise funds for communities affected by COVID-19, we cycled and ran many kilometres. Collectively, we raised about 10 lakh rupees in six weeks. Using our athletic side to help communities in need strengthened our bond. It remains a core memory for us.

When did you start to understand that your experience as a female athlete was different from that of your male counterparts’? How did that affect you?

There was always a lot of IPL (Indian Premier League) talk in school as well as a strong rivalry between the boys who followed football clubs. Many sports enthusiasts begin their journey by watching sports and fandom but for me playing acted as the gateway. I do reflect on this a lot because it’s not very often that you get involved in sports so deeply without having a background of watching it. I didn’t follow sports as a child because women’s sports were hardly televised or written about at that time.

When did you eventually develop an interest in watching sports?

I was 17 years old when I realised that there was an Indian women’s cricket team; the 2017 women’s cricket World Cup was the first time that I heard a women’s sporting tournament being spoken about. Watching that World Cup was a turning point for me. India reached the final, but England beat us by nine runs. That was a landmark event for the Women in Blue. When our team came back from England, the airport was packed with fans carrying garlands. They had never had this treatment. I remember feeling sad that I found out so late given that India hosted the 2016 ICC Women’s World Twenty20.

What led you to start She Talks Ball?

Once I started regularly watching women playing sports professionally, sometimes accessing matches via pirated sites, I got increasingly invested in learning more about the players. However, I found it difficult to find much information. Few writers were covering women’s sports. During lockdown, with little academic load, I decided to use my free time to write for lesser-known content platforms, even if the job meant using my Canva skills to create “Happy Birthday!” posts for different female athletes.

I got my first interviewing gig with Blue Pilgrims, a group of fans who support Indian men’s and women’s football. They usually organise watch parties or make banners to take to stadiums but during lockdown, they started hosting Instagram Live sessions with athletes. They asked me to host an hour-long Independence Day special with Aditi Chauhan, the goalkeeper of the Indian national football team. When I rewatch that first interview where I was thrown into the deep end with an athlete I idolise, I can see I’m a nervous wreck. But I enjoyed doing it and realised I had a decent presence on camera.

Zoom interviews for Women In Sports Inc., a community-run account on X, followed and helped me hone my video editing skills. One of the people I interviewed in September 2020 was Ananya Upendran, a former cricketer, who was the managing editor of Women’s CricZone at the time. A month later, she hired me as a freelancer. I was excited to work with a media outlet that was bringing international cricketers to the table. Soon, I found the need for a place to showcase the work I was doing for different platforms. She Talks Ball (STB) began in December 2020, halfway into my second year at college, as a portfolio of sorts. The name doesn’t just refer to women playing sports. It also refers to starting conversations around this topic through content and coverage, which by this point was my clear intent. I also didn’t want to restrict myself to interviewing athletes but also cover agents, sports photographers, journalists, even medical professionals. My thought was that it is worth hearing from any woman in the sports arena.

Why did it take so long for platforms like this to appear on the scene?

There is a women’s sports revolution brewing and, luckily, it’s happening as I am growing up. The pandemic spurred the world to reflect on how we watch sports — often, we watch sports played by men. The Ballon d’Or Féminin, also known as the Women’s Ballon d’Or, which is the highest honour that can be given in football, was established in 2018 — the men’s Ballon d’Or was established in 1956 — and anyone watching the ceremony was suddenly watching women win this award as well. The 2019 FIFA Women’s World Cup had a huge viewership. These things happened back to back and made people take notice.

Before I started STB, I connected with other content creators, some of whose platforms are quite big now — like the North American website Just Women’s Sports, the North American sports media brand The Gist, and women’s sports sponsorship consultancy Goals, whose founder Caroline Fitzgerald and I are now friends. Caroline’s podcast — The Business Case For Women’s Sports – breaks down the monetary benefits for athletes (which depends on the coverage of the tournament), how much female athletes are paid and how sponsors can support women’s sports. I think women like us are increasingly empowered to pick up a microphone and start a platform because there is more visibility for top-tier female athletes today.

You write, interview and report across social media platforms — Instagram, YoutTube, X — for STB.

It made sense to have my presence on multiple platforms because the goal was always to reach more people. I was fairly familiar with Instagram and YouTube. I joined X because publications started asking for my handle so that they could tag me in the content that I was creating for them. When I started STB, I simply changed my personal Insta handle so STB started with 300 to 400 followers, even though they were my friends. I think it was clever of me to not ask people to follow a new account of mine. I also chose to make a Google Workspace email because writing to radha@shetalksball.com sounds more professional than writing to shetalksball@gmail.com. When it came to populating the platforms with content, I quickly realised that the way to go about it was to first upload full videos on YouTube, and then share them as smaller clips via Instagram and X. My strategy for X was to tweet live to create a buzz. Instagram is a great informal tool, especially for sharing photos of myself watching a match, even if it is at home. It helps normalise the watching of women’s sports. Instagram was also where I connected with other creators and cross-promoted content. I got a lot of podcasting opportunities through that. Someone would see my clip of watching a match and ask me to share my perspective on an episode where they were going to break it down. I’ll admit these were often for a token episode. But even though I recognised the tokenistic nature of it, I was happy they were doing it. I did it in the hope that next time they’ll do more episodes featuring women and I’ve actually seen that happen.

How did you build credibility for your project?

Getting the first gig with an established platform like Women’s CricZone definitely helped. Viewers saw a new face interviewing famous athletes and asking meaningful questions, which led them to my YouTube channel.

Another milestone was when Chelsea FC Women reached out to me in 2021. I became a Chelsea fan in 2018 and a lot of my videos were centred around the Chelsea women’s team. The club’s social media is run by a media company called Engage Digital, who wanted me to help them expand their Indian fan base for the women’s team and asked if I could preview the UEFA Women’s Champions League final. Whenever I get opportunities like this I always leverage STB and they were happy for me to share it on my small platform. Months later, they reached out again to collaborate on a seven-episode series called She Talks Chelsea. This time, they gave me time with a different athlete on each episode. The episodes were eight minutes long, and included a build-up to the match, an interview, the results and match clippings which I was provided with.

Another milestone was the grant I received from the US-based Sports Innovation Lab around July 2021. When they wrote to me saying I was one of four women’s sports content creators in the world that they would like to sponsor, I first thought it was a scam. It felt unbelievable that my pet project in the field of women’s sports, which is already niche, was about to get funded by a party wanting nothing in return. I also felt that I hadn’t done enough to be worthy of being invested in. The co-founder is a former American women’s ice hockey player. I was proud to learn that my content had reached them. The grant gave me the financial boost to get media accreditations and attend events on my own. I was able to buy a recording mic and cover travel and stay to attend the AFC (Asian Football Confederation) Women’s Asian Cup in Pune and Navi Mumbai in early 2022. I was able to go to the stadium at a time when Indian and international media outlets were still not covering these matches and this enabled me to capture exclusive content, which was valued by publications and gave my name credibility in the world of women’s sports content.

Tell us a little more about the grant and attending a sports event as a freelance journalist.

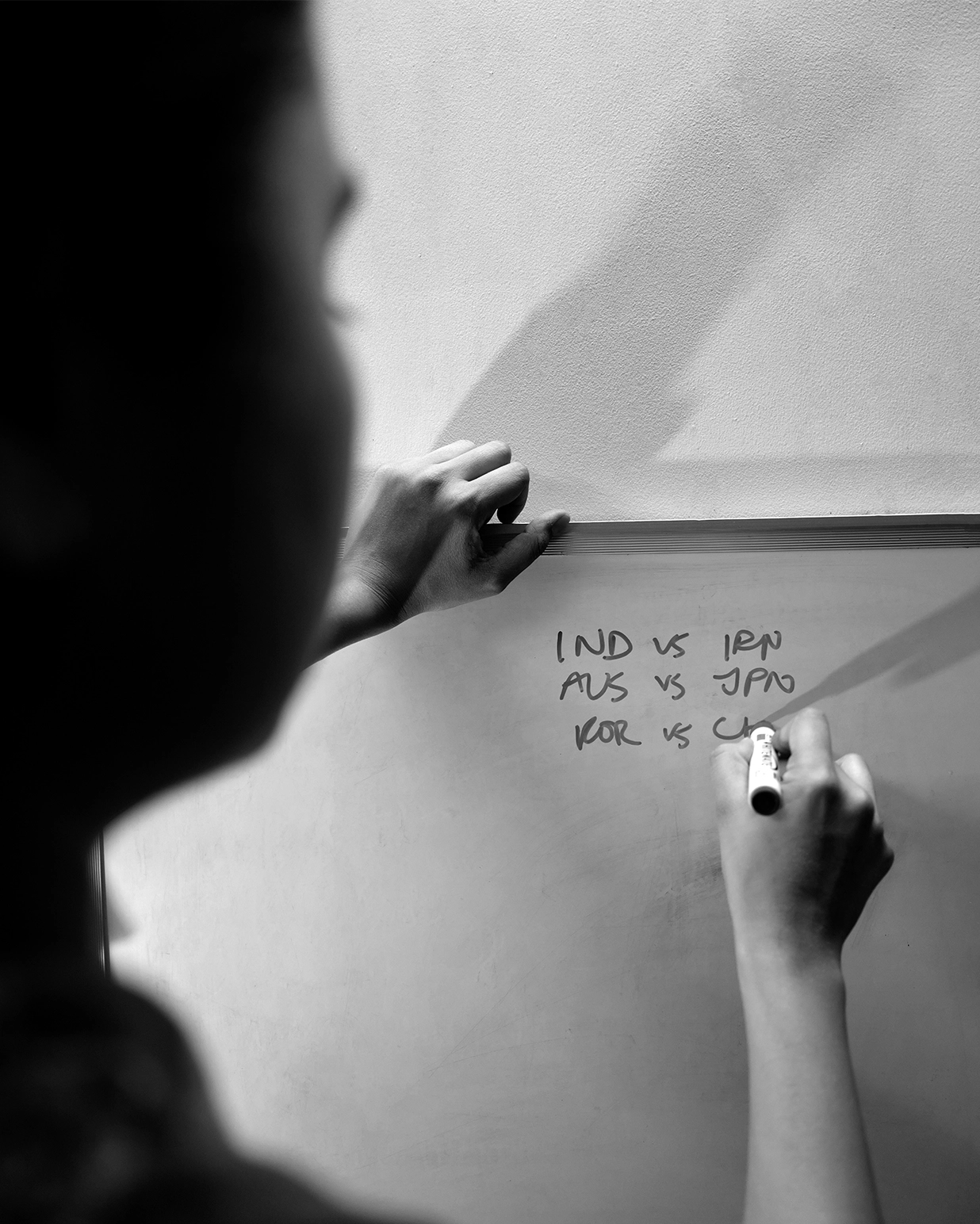

The grant came through smoothly but when the media accreditation applications opened up for the 2022 AFC Women’s Asian Cup, I learnt that prior media certificates or a signed letter from an editor of a publication is required. I started searching for a foreign publication that would like to cover the tournament but couldn’t send their media team to India. Australian publications seemed most suitable since they need coverage in English, as opposed to ones from Japan or China. I found Beyond 90, an Australian digital news platform, via the internet. They have a strong women’s sports’ presence on their website, which I liked. The editor-in-chief was very keen to use my content. I submitted the letter she sent along with my application and the accreditation came through a month later — while I was having breakfast during a winter trip to Ranthambore. Thrilled, I created a content coverage plan with Beyond 90. I missed attending the first few weeks in person, having contracted COVID-19 but, luckily, the press conferences were live-streamed. I would watch the games on television, attend press conferences online where I would ask questions and write my piece. By the quarter-final stage, I was cleared to attend.

It was my first time in the media box, which is so different from a ticketed experience because you are served food, have an unobstructed view and you get to walk back into an air-conditioned room to interview players. I also got to sit shoulder to shoulder with journalists I admire. I would observe their way of working while also trying to find my own style. Often, we’d go out together to grab dinner after the games.

You also attended the Women’s Premier League (WPL).

I attended the WPL in 2023. I spent the entirety of March in Mumbai, interning with the UP Warriorz’ media team. By that time, I was fairly credible. Even some of the players were familiar with my work for Women’s CricZone. My job as a content intern involved attending training sessions, assisting the producer on sponsored shoots and covering crowds at every match. When the team wasn’t playing, I got to attend matches played by other teams for free. But in the case of the latter, I found myself fighting at the gates with the ticketing partner. So I had a very interesting dual experience of being the average spectator on my days off and also having exclusive access with a new team finding their footing in women’s cricket.

It was my first time covering cricket in such depth and it led to several insights. The athletes, who are such superheroes, are very humble off the field. I remember Shabnim Ismail, a South African fast bowler — the fastest female bowler in the world — coming to a UP Warriorz training session straight from the airport. Although jet-lagged, she struck up a conversation and asked me where she could find a tailor. They’re just like the rest of us but they happen to have the ability to be formidable opponents during a game. You never see how funny they are at press conferences because they’re all trained to speak to the media in a particular way.

All the franchises treat their players well but I was a bit disappointed with the attitude of other stakeholders. For example, the organisers scheduled an anthem shoot for the team in the peak of afternoon heat on a dusty ground, which the men’s team would never have been subjected to. It may be a contractual obligation that the players need to get done but there’s a way of delivering it. Surely, anyone would think that’s a bad time for shooting or that refreshments would need to be provided, at the very least. Even at this point, they don’t take the women’s team as seriously as Rohit Sharma’s or Virat Kohli’s teams. So there is room for improvement.

What did you observe at international events?

Any tournament is defined by its host — not the country or city — but the federation. When I went to Nepal to cover the South Asian Football Federation (SAFF) Women’s Championship for STB and Scroll.in in 2022, I realised that it all comes down to the amount of money the organisers have and the viewership they get. Not many people watch the SAFF games so it was hosted in a stadium that would get waterlogged; the match would be cancelled if it happened to rain. I attended the FIFA U17 Women’s World Cup in Bhubaneswar, Goa and Navi Mumbai in the same year, and each location was a consistently pleasant experience. The local organising committees are trained and employed by FIFA and they operate at a very professional level. If you miss a press conference, it’s in your inbox the next day. It was of a higher standard than the WPL, which is hosted by the BCCI, even though both took place in India. FIFA had that mark of quality, according to me, and global journalists were in attendance. The journalists, however, disappointed me at times. I remember an incident that took place in the mixed zone — a tunnel through which the athletes walk right after a match, and where media persons are free to stop an athlete and ask them questions – during the FIFA U17 Women’s World Cup in 2022. A lot of the girls were happy to stop and talk to me because I had done my research and knew who they were. Whereas other journalists would stop players, shove the mic into their faces and ask them what their names were. A Brazilian athlete loudly asked, “Why should I stop for you?” and I agreed. We’re all holding a sheet with the teams’ line-up mentioned in it so there is no excuse to not know anybody’s name. I realised that it is also important to establish credibility with the athletes and not just your viewers or platforms.

You have often mentioned how aware you are of the space this project occupies in this current time in women’s sports history. What is at stake here?

Simply put, I’ve seen how the lack of coverage regarding women’s sports has affected a girl like me who wanted a role model and a career in sports but didn’t have access and wasn’t aware that the latter was an option. I have also seen how, now, with increasing support, the stadiums fill up with families who bring their girls and boys to show them that girls also play sports. I think that is what drives anyone covering women in sports. Not only do you need to show it to a girl but also normalise it for a boy and both of them will normalise it for five others tomorrow. You don’t have to change the world of women’s sports, you just have to expose a few minds to it. These athletes are exceptionally talented and entertaining, and my role is to make them visible. The athletes will take care of the rest.

Tell me about the community you have cultivated through this work.

It includes sports fans, those who don’t care much about sports but are interested in seeing something different and those who are seeking entertaining content pertaining to women’s sports. When I came to IIMA, a few of my batchmates told me they had seen my content. X, in particular, has that amplification effect. I have the privilege of access so I make good use of it. I take information that isn’t well broadcasted and disseminate it to those who aren’t able to access it via mainstream media and hope that they find a new source next time — they might even post live match updates instead of reposting mine or buy a ticket and take their family to a game. Social media is very powerful in that sense. I do believe that power comes from the masses. Recording my personal struggle may not amount to much but a thousand people tweeting and questioning why attending a women’s cricket match is such a cumbersome process might encourage organisers to invest to make it a better experience.

My Ashoka University women’s football teammates and I are now not only women who play together but also watch together — we support and argue about our favourite teams together. My parents know a lot more about female athletes now. They understand the value of covering women in sports and that it is actually a legitimate line of work.

At the links below read more from the Creating Spaces series:

Shruti Taneja, Nivaala, Founder

Anchal Notani, Two Extra Lives, Founder

Shweta Pai, Muuyee, Founder

Payal Shah, Kobo Fermentary, Founder