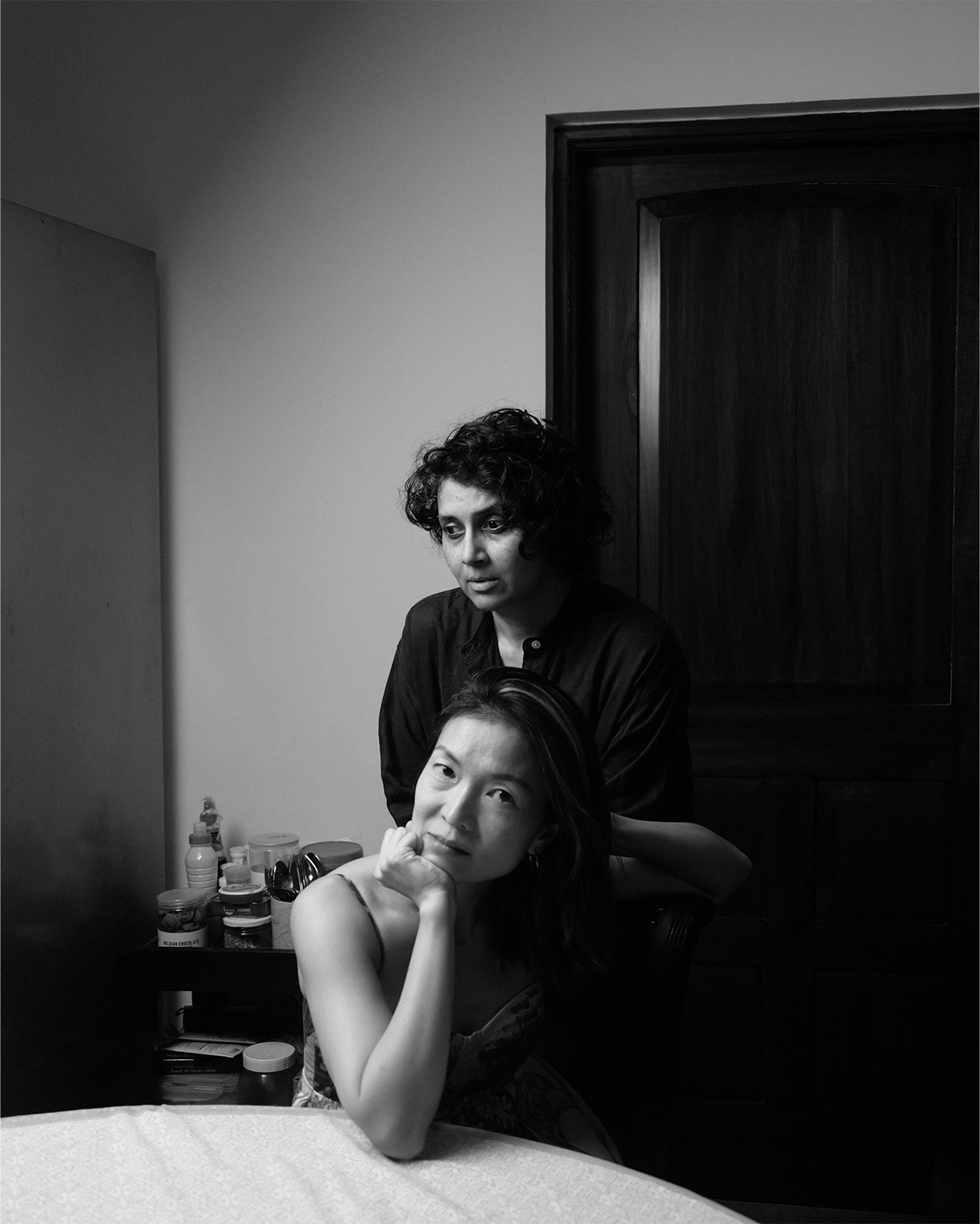

Payal Shah

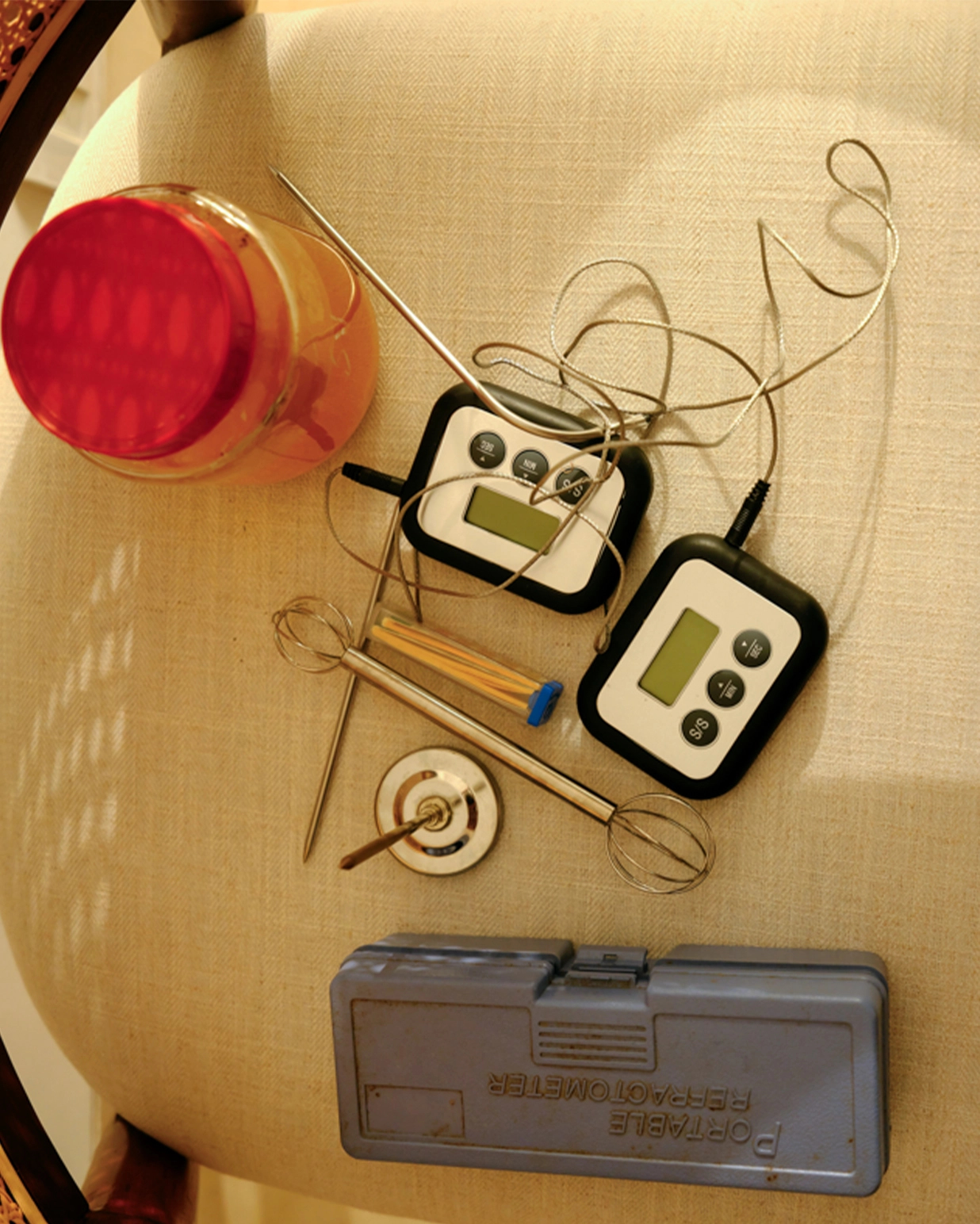

Kobo Fermentary, Founder

Location: Bengaluru

You would be hard-pressed to find a hobbyist or professional fermenter in urban India today who has not heard of Kobo Fermentary’s Payal Shah, the self-proclaimed “shepherd of microbes”. Shah features on panels, festivals and workshops on fermentation organised online and offline across the country. A lot has been said about our collective interest in reclaiming the act of home cooking and acquiring a taste, both figuratively and literally, for speciality foods since the lockdown, and many of these are products of fermentation. So her relevance in the food community is obvious.

In his foreword for The Art of Fermentation by Sandor Katz, Michael Pollan writes, ‘To delve into the world of fermented foods is to enter the community of fermentos, who happen to be a most interesting, eccentric, and generous bunch.’ In fact, those who follow Shah on Instagram range from architects and others featured in this series to professional chefs and bakers, fellow farmers and fashion designers. Yet, one wouldn’t guess she wields this kind of influence on a first meeting; she is soft-spoken, bespectacled and comes across as a certifiable nerd in the best way possible, which becomes evident quite quickly with the way she finds connections between diverse topics that intrigue her. When describing significant events, she follows tangential threads and tells interconnected stories that don’t always follow a linear timeline — a tendency explained by her neurodivergence.

What is most compelling is that her community of followers didn’t just stick around during the sourdough wave only to lose interest after. Shah’s weekly AMA (Ask Me Anything) on Instagram, which was started as an informal knowledge resource for anyone who might be interested in fermentation, is in its fifth year. Often, she is asked troubleshooting questions. Whether it is by reminding her community to frequently burp or release the pressure of beverages that are in the process of getting fermented or by helping them loosely calculate how much salt or sugar they need for the microbes to kick-start the fermentation, Shah is the one who shepherds her community through their fermentation experiments.

Creating Spaces is a series where Verve spotlights women working on community-driven creative projects across realms — food, sports, healthcare, parenthood, art, design and fashion. Each one has created a unique space, be it virtual or physical, while also challenging institutions and changing mindsets.

Through exclusive interviews and shoots, we delve into the motives that drive these women, their reflections on the influence their work has on their communities, and how their practices address the larger challenges facing urban Indian society.

Tell us about your relationship with food during your growing-up years. What did you like to eat?

My family is obsessed with food so there was always a lot of conversation about it. We have strong opinions on where to eat, what to eat and how to eat it. My mother and grandmother are fantastic cooks. Both my sister and I ended up becoming decent cooks. And even though I’m super slow, I do understand flavour really well and that comes down to physically being around food so much — it’s also a skill that has been passed down through generations.

Both sets of my grandparents, who are Gujarati, spent most of their adulthood in Calcutta (now Kolkata), so my parents grew up in this mix of different cultures. They ate a variety of food, and all of it was home-cooked. My parents moved to Bengaluru when they were in their early twenties and that is where my sister and I grew up. The mix of influences meant that in a day you’d have the Gujarati rotli-dal-shaak but then you’d also have a bisi bele bath, which is a dish from Karnataka. My favourite thing to eat growing up was my mother’s puran poli, which she made every year for my birthday.

How did you come to enjoy fermented foods?

My grandmother, who was very driven by the idea of zero waste, always had some fermentation project or the other going on an annual and weekly basis. Often, she would transform kitchen waste into delicious condiments and dishes and challenge us to guess what the ingredients were. She also generally made a lot of pickles because my grandfather was a fan — all of us are in my family. We always made fun of the fact that he would eat almost as much pickle as the vegetable dishes on his plate. There were always at least five different types on the table. My love for pickles led to my interest in how they are made. The year’s pickling project lasted four to seven days. They had to be sunned on the roof and brought back each day, and this was usually my job during the summer holidays. I have fond memories of stealing a few pieces at every stage. But it wasn’t until I was an adult that I really got into making it myself.

How did your fermentation journey begin?

My own fermentation journey began with ginger beer, not with pickles. I kept making ginger beer for many months. It was an obsession and it blew my mind each time I made it. Eventually, I found Sandor Katz’ book Wild Fermentation in a second-hand store and that set me off in another direction. That was in my mid to late twenties.

I was far away from the food industry at the time. I had a master’s degree in organisational psychology and I had been setting up the Indian arm of a US-based IT company for seven years. At that point, I was actually studying to give the GMAT (Graduate Management Admission Test) because I was considering going back to university. Because I’ve always done fermentation for fun, I had a few things in the works. A friend came over and tried one of my fermented drinks and said he’d pay 500 rupees for it. I started a small focus group. It wasn’t anything formal, I was just running ideas by my friends and gathering data.

How did you start Kobo Fermentary?

I started Kobo in July 2018 with a lot of encouragement from my friend and business partner Candice Lock Mirchandani. She’s a chef who runs a sandwich shop called Candice’s Gourmet Sandwiches as well as a Mexican restaurant called Chinita in Bengaluru, and has been involved part-time since the beginning. She doesn’t ferment but understands flavour really well so she’s been one of my guinea pigs. She’s really good at taking all the data that’s in my brain and making it accessible and getting it out to other people whether it’s through the playbooks or the videos we create on YouTube. She was the one who encouraged me to start Kobo and also create a digital space for it — I was actually quite apprehensive in the beginning. I had very successfully stayed off social media for eight years before I created the Instagram account but she insisted that to remain relevant, one has to put oneself out there.

How did being diagnosed as neurodivergent intersect with it?

If I rewind, there were a few things that happened parallelly in my life. My neurodivergence journey is a long story and a different one from my fermentation journey. One is born neurodivergent –-- it is not something you acquire or can catch. I was aware that I was neurodivergent but I was only officially diagnosed about three years ago after pursuing a diagnosis for about four to five years. That was a bit of a struggle.

In 2020, I was running a fermentary and supplying products to a few restaurants, cafes and subscribers, and also stocking in different speciality food stores. When the pandemic happened, I closed it down and it was one of the best things that I did because I was going through a neurodivergent burnout. I’ve experienced these since I was 12 but this time my symptoms were much more intense. This was before I had my official diagnosis which revealed that I’m autistic and have ADHD. I have also been diagnosed with dyslexia and dyscalculia but their influence on my life is less. Looking back, I value the experience of running it from my home and then a commercial space but I am even more grateful for realising that it was not a sustainable way of working for me in the long-term.

How is fermentation compatible with your neurodivergence?

Just to be clear: understanding my brain and how it works was a different process from getting a diagnosis. The latter required me to navigate through the Indian mental health system which is quite broken. I’m not implying that it is a lot better in other parts of the world. The former was through my own research, which also happens to be how most people figure out that they are neurodivergent whether they pursue a diagnosis or not. That realisation helped me make better decisions compared to the internal voice that would self-flagellate. It is interesting because my sister also has the same type of neurodivergence — we are both AuDHD, we have autism and ADHD which often occur together — and yet the way her brain works is so different from mine. Every neurodivergent person is unique and their brains are wired differently, so I always find it interesting to meet a neurodivergent person and ask about their work projects or how they might approach a solution to a problem.

The reason that fermentation works for me is because it helps me live my everyday life a lot more conveniently. My combination of neurodivergence makes me process vast amounts of information in milliseconds but my hands can’t keep up. So, making a simple dinner of soup and salad, for example, can take me over three hours but the end product will be amazing. It is the actual execution where I’m slow. That is also why running the fermentary didn’t make sense for me because my strengths lie in researching and processing knowledge or information versus making products by hand, which takes me too much time for it to be a viable business.

Fermentation provides me with a pantry of instant ingredients that help me to add flavour to food easily because a lot of the work has been done in the jar by the microbes. For example, I make this rasam miso (rasam is the flavour and miso is the product), an idea I got from a friend who makes pre-seasoned balls of miso where all you do is drop that in a cup of hot water and it becomes miso soup. Whenever I’m sick I crave rasam, so I make the rasam miso; all I have to do is boil water in a kettle and I have instant rasam. I love that I don’t have to go through a whole process each time. I can condense the flavour in a jar, let microbes do their thing and the rasam is ready when I want it.

Another reason why fermentation is sustainable for me is that every project has a different timeline to achieve the final result. My ADHD brain can hyperfocus on things for a short amount of time and then it gets bored. This is compatible with the fact that fermentation requires me to do half an hour of work now and then 10 minutes tomorrow and then 15 minutes next week. I also like that there is no fixed recipe I need to follow. A lot of variables keep changing and these little bits of time are easy on my brain and I am able to sustain interest. I can use this knowledge to my advantage. The autistic side of my brain loves the research — going deep into something and then following the offshoots. My brain makes connections in a way that is interesting and I’m able to show a different perspective that someone else may not have thought about. You may think of fermentation as a slow process but I see it as convenient.

How did the weekly AMA (Ask Me Anything) on Instagram start? And what urged you to continue it as a free resource rather than monetising it?

The weekly AMA started after the pandemic hit. I closed the fermentary when the lockdown was announced. Like everyone, I was paralysed for the next three months. It was a shock to everyone and I wondered what I could do to help. Some of us also had more free time to pick up a new hobby and that is what propelled the decision to post more about how one can ferment and to share ideas for projects that others could take up. I got many requests from those looking to brew wines, beers and the like and I was answering so many questions via DMs. A friend of mine made a good point that all of this knowledge was staying within closed chats and I also noticed that the same questions kept cropping up. I still get questions every single week from people from all over the world. It has been such a good resource for people to learn about fermentation — I still learn something new from it every week.

I kept the model free because when I was learning about fermentation, I didn’t have a resource like this and I would have been much further ahead in my journey if I had had that. I just happened to be really good at research. It’s as if my brain has its own internet so I can easily link information and retrieve it from an increasingly complex network. I was also answering questions via DMs anyway. I don’t charge anything for it but I also do it on my terms. I’m okay with skipping a weekend or being late or missing some questions. I would have worried about that earlier but I don’t anymore. In the past, I have also let people buy me a cup of coffee sometimes which I should bring back. It’s nice to let someone give me a treat as a way to thank me. In a spiritual way, it’s also about putting out that good karma. Ultimately, I do it because I love it.

Tell me about the Kobo community.

The Kobo community is formed of those who are genuinely interested in food and making foods from scratch or using alternative methods of cooking. It is actually the fermentation community and I don’t call it my community because it is a space I belong to as well. I learn from different people who are fermenting stuff around the world, who are all doing unique work. Everyone is on their own journey. I’m conscious about what information I’m putting out and how that encourages someone to find their own way with this interest. Sometimes, I meet people who tell me someone is trying to be like Kobo or wants to be “a second Kobo”, or they’ll tell me, “I love your work so much, I want to do what you are doing” and I encourage them to go make it their own. There’s so much value in finding that different path.

Is this why the fermentation guides you sell have “non-recipes”?

Firstly, I think I’m generally a nonconformist. Secondly, I have a fraught relationship with precision — it’s so hard to explain this because my autistic brain and ADHD brain are constantly battling this out every day and every minute because there’s a part of me that loves precision but also a part that hates it, feels trapped by it and rebels against it. And I’m trying to find that compromise. The idea of non-recipes comes from the fact that there are so many variables in not just cooking but understanding how fermentation works because there’s physics, chemistry, microbiology, botany, etc. at play. There are so many scientific processes taking place at once, and yet it’s not precise. It changes, like the music on a DJ’s console, because if you change one aspect, it affects all the other aspects — if you leave something out, that changes everything. So there’s a lot of room to play but to play, you have to understand how the fermentation happens and then it becomes interesting and fun. Fermenting is not like baking where it has to be precise or it doesn’t work. I find that it’s the middle road that works for me — it’s not precise but it’s not up to chance either. I like to take the imprecise route and avoid sharing recipes or processes that have too many steps because fewer steps work better for my brain. I also play with elements like flavour which gives me enough dopamine for my ADHD brain while also keeping my autistic brain engaged. My approach also helps me demonstrate how the results in fermentation are not always consistent and they really depend on one’s skill level as well as the ingredients. One person’s mango water kefir might not taste like somebody else’s because there are so many variables.

What insights has running the AMA sessions given you into the psyche of those who are curious about fermentation?

It has helped me recognise that fermentation is not for everybody. You have to want to go on this journey — otherwise, feel free to buy your kombucha. The AMA sessions have a big part to play in communicating that. When you’re fermenting you have to be okay with things not turning out the way you had planned and with starting over. The AMA is also a space where I speak from my experience rather than give instruction. People can take what they want from it and that encourages them to at least try. In any case, I enjoy what I do, and would have documented it anyway. It’s just that I’m doing it on a public platform where people can take comfort in seeing that I also deal with failure or restart ferments, and that helps them to navigate the unknown.

Can you tell us about some of the ways in which running Kobo influences your work, that we may not be seeing online? What have been some of the unexpected outcomes for you?

My line at parties has often been that I help people cook better and that always gets those I’m socialising with interested. A lot of my work is going into research right now. Often, I get asked a question that I don’t know the answer to, so before I respond on Instagram Stories, I dive into research or speak to experts. We produced five playbooks last year, and there are more in the works. Of course, the diverse work I have done through Kobo has become a testimonial for my consultation work, which actually pays the bills.

I also started a newsletter in January. What you see on Instagram is often so surface-level and I’m quite sick of being at the mercy of the algorithm. So I am leaning more towards Substack now — the format allows me to be flexible and also offers more agency in terms of the content and how it is presented, which works well for my ADHD brain. I do plan to talk a lot more about my neurodivergence on it because a lot of people have expressed a strong interest in reading about that. I have already recorded three podcast episodes with different guests.

The newsletter might also become a place where I share more about my travels. I’m currently researching flavour matrices, coffee and cacao. Next, I’m travelling to a bunch of farms across Wayanad, Nashik, Chennai, Auroville, rural Telangana and Ooty. I was in Chennai last March for an event hosted by Desi Dairy Dialogue (DDD) — an Indian cheesemaking collective co-founded by my friend, Washington-based writer Trevor Warmedahl who spent four months travelling and living with shepherds in Gujarat and studying camels in Rajasthan. I had met him first in Georgia in 2022. We had connected online a long time before that and it just so happened that we had one day overlapping during our travels in the Caucasus. It was so interesting to go to these remote places in Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia, and taste ferments that originated there because these are such ancient practices. Back home, at the DDD gathering, there were four buffet tables laden with quality Indian cheese, from makers like The Farm and Namrata Sundaresan’s brand Kase Cheese.

Since you started Kobo, what observations have you made about the changing tastes of people in India when it comes to fermented foods?

None of this is new. Most of our grandmothers made pickles or used fermentation to make curd or dosa batter. Fermentation is not just something Danish restaurants are doing; our ancestors have been doing it for so long. But I have observed that over the years, people are travelling a lot and the exposure is more. Korean food, for instance, has really hit it off in India and it is cool to see acceptance of cuisines that are not Indian. Kombucha is available in so many stores and on restaurant menus and it’s definitely a legitimate non-alcoholic beverage option now, which is great to see. There’s more awareness about fermentation and flavour, and also its contribution to gut health, so it’s been most interesting to see the evolution of taste in that direction.

At the links below read more from the Creating Spaces series:

Radha Lath Gupta, She Talks Ball, Founder

Shruti Taneja, Nivaala, Founder

Anchal Notani, Two Extra Lives, Founder

Shweta Pai, Muuyee, Founder