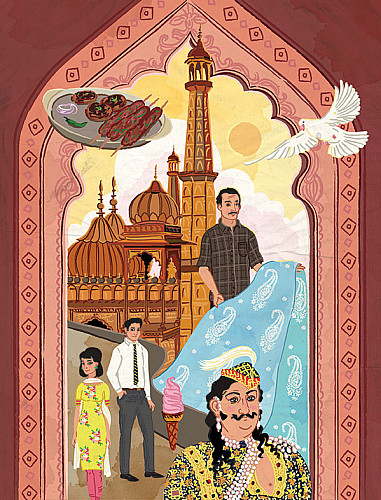

Lucknow: Ghazals and Galouti

Way back in the 1960s, I dodged huge, red-bottomed langurs on my way to school. My grandmother’s red-brick bungalow stood in a tree-lined lane that, apart from mischievous monkeys, had aristocratic families living in elegant homes. Young Romeos, nattily dressed, also on their way to school, would hum ditties from Hindi films as they cycled past. My principal, an Australian nun who could sing Rabindra Sangeet, held my hand and taught me to recite poetry, sauntering under the mango trees in our school compound. It was a different life altogether…sweet, romantic, laid-back…. We didn’t rush from one tuition class to another, and, yet, we didn’t fare too badly in our exams, or, later, in the larger world outside.

Lucknow, in fact, has much to boast of in the field of academics. Nawabi culture may have bequeathed its famed tehzeeb to the city but westerners set up schools and colleges that imparted a liberal education to generations of students. In my time, most of the boys were either from St Francis or La Martiniere, irrespective of whether they were Hindu, Muslim or Christian. La Martiniere sprawled over 650 acres and overlooked the Gomti river — what a campus to study and play in! Even today, you can recognise a 60-year-old as a La Martiniere product from his Anglo-Indian manner of speaking. And, oh yes, there were those from the elitist Colvin Talukdars’ Boys School set up in 1889 to cater to the sons of the landed. Filmmaker Muzaffar Ali is an alumnus of this school spread over a more modest 60 acres. Most of the girls went to Loreto Convent, started by an intrepid group of nuns from Darjeeling in 1873, or its branch, St Agnes Loreto, or La Martiniere Girls’ School, and for further studies they usually opted for Loreto College or Isabella Thoburn College. Actress Bina Rai and writer Quaratullain Hyder passed out from the magnificent portals of the latter. For those who couldn’t get admission to these schools and colleges there was a rash of other institutions.

Another centre of learning, Lucknow University, all of 200 acres, is in keeping with the oriental ambience of the city. Within the environs of its buttery-cream buildings, with glistening cupolas, symmetrical arches and high, wooden ceilings, a wide-ranging choice of subjects is available to enthusiastic students. A clean-scrubbed, bright-eyed youth, taking a walk after dinner in the moon-lit grounds, has opted for an unusual combination – Defence Studies and Hindi Literature. An ex-student I meet the next day has four MAs and a doctorate under her belt! Clearly, the university, established in 1921, inspires much academic activity. As it does romance. Love has happened to many a youngster here, even as they poured over books or fought one another in union battles.

The amalgamation of Nawabi and British cultures imparts a fascinating skyline to this city that was established in 1753, after canny nobles from the disintegrating Mughal court in Delhi migrated to Awadh. Impressive domes, majestic darwaazas, kothis of begums, maqbaras of royalty, church spires, European-style palaces and clock towers dot the cityscape. After the Mutiny of 1857, the British vindictively destroyed many a mosque and kothi, but, fortunately, quite a few of the grand structures of the Nawabi period survived the onslaught. Many of these historical buildings were renovated to accommodate British needs and, post-Independence, to house free India’s offices. In fact, even before the Mutiny, after the annexation of Awadh in 1856, the English had started usurping native property like the Hayat Baksh Kothi, which the Chief Commissioner moved into. Renovated several times over the years, this became the august Raj Bhavan after 1947. As a school student, I was quite unaware that the Central Drug Research Institute, where we were taken on a study visit, was once the delicately ornate Chhatar Manzil Palace, or that when I walked the streets of Lucknow I was taking a walk through history!

When I visit this exotic city almost half a century later, even though much has changed over the years, I am enthralled by its intrinsic charm, all over again. Yes, it takes strong nerves to get accustomed to its chaotic traffic, buffaloes and all; and it is heart-rending to see the garish, indescribably ugly buildings that have replaced many of the mansions on the street where I lived, A.P. Sen Road, that was named after a barrister who is said to have come from censorious Calcutta to this city of poetry and ghazals so he could marry his cousin. But, thankfully, some of A.P. Sen Road’s original inhabitants continue to live here, unaffected by their new-rich neighbours. As I stand, gazing, outside the gates of a bungalow where a friend lived, a gracious lady from within asks if I am looking for someone. Unhurriedly, she proceeds to tell me about my friend’s entire family whose members now live in different cities!

I encounter similar courtesy almost everywhere I go. Ram Advani, who has been running a bookshop, since 1951, on the stylish Hazratganj, spares me several hours on the history of the city where his parents set up home in the 1920s. At his shop, I meet another gentleman who exemplifies chivalrous, old-world manners. Mr Nasir, a true-blue Lucknowite, with generations of his family having lived here, offers to take me down Hazratganj and introduces me to several old-timers. “I have met you before,” say some of them, though they couldn’t possibly have! It is their way of making me feel significant and at home….

Hazratganj, in my school days, was the fashionable promenade of the city. Stylishly-dressed young men and ladies strolled here, stopping for chaat, popcorn or a Softie ice-cream, while eye-balling one another. This innocent pastime was called ‘Ganjing’. You caught the latest English film at Mayfair, an art-deco theatre in Ganj, or spent a leisurely Sunday morning, with cold coffee and almond biscuits, at Kwality’s. Brides-to-be shopped for saris at Modern Silk House while housewives bought kitchenware at Aazem Ali and Sons, one of the oldest shops, still going strong.

Sadly, many of these popular haunts are no more. The iconic Mayfair theatre and Kwality’s have closed down and only a shell of the theatre’s grand staircase stands in neglected darkness. Much to the chagrin of heritage lovers, the 100-year-old kotwali, that maintained law and order on this road, has been demolished and a multi-storey car-park built in its place.

Hazratganj was built a little over 200 years ago by Nawab Saadat Ali Khan who felt humiliated when he read reports about the wretchedness of his city’s roads. So he decided to build a grand road that would be on par with Calcutta’s Chowringee, connecting his Scottish-style country house, Dilkusha, to the British Residency. Ever since, this handsome street has been Lucknow’s jewel in the crown. In 2012, as part of its 200-year celebrations Ganj was given a face-lift and, to the credit of the town planners and the shopkeepers, it was done in a tasteful manner. Nineteenth-century-London-style wrought-iron lamps, smart benches, fountains, small gardens and uniform, black-and-white shop frontages were part of this up-gradation. A former Supreme Court judge drops by at Ram Advani’s to enquire if the gutter, flooding outside his bookstore, has been cleaned. It has, with the mayor, a former faculty member of the University, having personally got the job done. Clearly, Ganj is the pride of Lucknowites!

If only the same pride would manifest itself in the rest of this once-regal city…except in a few prestigious areas, an ubiquitous smell of urine accosts your senses. The approach road to the impressive red-brick Charbagh railway station is lined with men shamelessly relieving themselves. Had the previous chief minister built public toilets, instead of monuments of herself in stark, expansive parks, she might still have been occupying the CM’s chair. Now her statues stand in pitch darkness because her successor is saving on electricity and won’t allow lights to illuminate her vulgar wastage of taxpayers’ money. I wonder what the female security guard, protecting one of her handbag-clutching statues, does when she has to answer nature’s call.

Apart from Hazratganj, another street that is a shopper’s paradise is Khun Khunji Road in the old city area of Chowk. Shop after shop stocks exquisite saris, salwar kameezes, bedspreads, delicately embroidered with shadow stitch, known as chikan. Polite salesmen happily display their wares in shades of pastel-pink, sea-blue, pista-green, lemon-yellow and milky-white. They even offer you tea as you mull over the vast array spread before your fascinated eye. After you have had a field day feeling like the royal women of yore you can refresh yourself with a tall glass of thandai or creamy lassi at one of the numerous shops selling milk products, though old-timers are choosy and have their favourites.

Lucknow has sometimes been described as a city of decadent culture. Decadent or indulgent? If you use the gastronomical yardstick, it is truly a city of indulgence. From delicately-flavoured pulao (as opposed to over-spiced biryani), sold even at Charbagh railway station, to the light, fluffy shir mal and melting-in-the-mouth galouti kababs, Lucknow continues the tradition of its royal kitchens where cooking was a highly-developed art. I remember a classmate bringing saffron-flavoured shahi tukra to a school picnic! And even today, school children’s tiffins are more likely to have pulao than boring sandwiches. A friend recounts that her mother made soft raughani rotis (the flour was kneaded with milk and cream) for breakfast and that she now makes them for her son.

And so, traditions are passed down from one generation to the next…and the capital of Uttar Pradesh – a state symbolic of much that’s wrong with governance – preserves its royal repast, even as governments come and go.

Related posts from Verve:

Verve Trending

Sorry. No data so far.

us on Facebook to stay updated with the latest trends