The Elegant Alternative

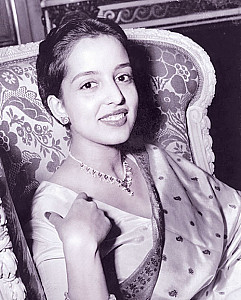

Style icon Leela Naidu consistently bucked trends and resisted easy judgements of her career, her fashion or her private life – and in doing so, created a whole new iconography of beauty, says Supriya Nair

It happens all too rarely, but sometimes, when you are reading a book on your daily commute in a packed Mumbai local, someone will detach themselves from the hive of bodies to ask you about it. The cause will generally be a book that has made you laugh out loud, or weep in public, or the latest Chetan Bhagat. The pleasures of Leela Naidu’s biography, Leela: A Patchwork Life, published earlier this year, are more refined; but all the same, it caused more than one lady to lean over, examine the cover, and then ask me how I had procured it, and how much it cost, and did I – visibly from a giddy generation of the post-Sush-and-Ash era – know who Leela Naidu had really been?

Who, indeed? Leela Naidu remained famous in India long after the siege engines of the PR machines and the dissolving limits of the news cycle turned celebrity culture into a panopticon. To the post-pageant public, she was always the Miss India (1954) who had made it to a definitive list of the ten most beautiful women in the world, back in an age when the Indian woman came somewhere above elephants and snake charmers, and perhaps ranked a little below bejewelled maharajahs and austere freedom fighters, as exotic representatives of their country to the West at large.

Her appeal to her compatriots was, in all likelihood, touched a little by the same ideas of foreignness, too. She was a biracial woman, as much at home in Europe (her mother was an Irish Indologist, with Franco-Swiss roots) as she was in India. Her career spanned a multitude of roles. From making documentary films for JRD Tata, to dubbing for Chinese martial arts films in Hong Kong and acting as unpaid secretary – her words – to husband Dom Moraes, to being the muse on whom Salvador Dali’s Madonna was modelled, to acting in the handful of films that established her legend as one of the loveliest women ever to grace the Indian screen.

For a woman less serenely honest and less elegant, the word ‘dilettante’ may have come to mind. How else to explain someone who had started out at more or less the same time as Madhubala and Waheeda Rahman, but whose body of work was a mere fraction of theirs: a woman who, according to her biography, was spotted by Raj Kapoor and lined up to be a marquee name for his RK banner – only to turn him down? It may be impossible today to imagine a beautiful woman becoming an icon for seeking less attention, rather than more. But Naidu was only being true to her sense of aesthetics, which found little common ground with commercial cinema.

She was a woman truly at home in the world, and her photographs from the time confirm it. In the simple drapes of her saris, free of make-up, she travelled through the country with poet-writer Moraes; whether she was taking dictation from Indira Gandhi or protesting on behalf of landless Dalits, she was the consummate face of an enlightened, independent India, still fired by the ideals of independence, impatient with consumerism and wary of social exhibitionism. The same appeal was evident in those films of hers, chosen judiciously across the decades – Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Anuradha, Merchant-Ivory’s The Householder, and Shyam Benegal’s 1985 classic, Trikal. Years later, Benegal would say that she ‘breathed innocence and tranquillity’ into her performance. It was a succinct description of what she represents in those black-and-white frames of her early life.

But she was equally at home in couture. The 1960s and ’70s, the decades of the birth of cool, were portended in the casual grace with which she carried herself in the fashions of Europe and the USA. There were compliments from Ingrid Bergman and salutes from Jean Renoir and David Lean. It wasn’t about switching cultural codes: in the girlish frocks and evening gowns of her modelling shots, she was as Indian as she was in saris, and that was the beauty of it. Writing after her death, Vikram Doctor said, “Naidu was one of a group of beautiful Indian women who, from the ’40s to the early ’60s, helped create an idea of a beautiful, elegant and accomplished new nation. This included Maharani Gayatri Devi of Jaipur, the other name that people remember from that ‘10 most beautiful women’ list and Nayantara Sahgal…. All these women shared a certain style. While unmistakably Indian and nearly always dressed in saris, there was also a Western air to them as well. They all had Western connections … and they presented themselves in a mix of Indian and European styles.” The mix, in Naidu’s case, was pitch-perfect. She rose beyond the traditional definitions of signature style as a single classic look or a set of influences. Her style was not about fashion; it was about feeling.

The very thought of a woman in rayon saris and flared skirts rising to the top of a list of classical beauties seems idiosyncratic today. We are used to seeing beautiful women who are not only icons of taste, but also of accomplishment. They are women who act in films and walk the ramp; they work as designers and news channel pundits and high-profile entrepreneurs; they head famous families and corporations; they are photographed at parties; they define the labels they wear. If Naidu did any of those things over the last decade, she managed to avoid all attention to it.

We don’t think of the starry radiance of Gayatri Devi or Audrey Hepburn when we think of her, nor yet the sun-drenched charm of Madhubala or Sophia Loren. Hers is a cool, chameleonic appeal: gracious, reserved and supremely unruffled. The cover photo of her biography, taken in her youth, is a shot overflowing with joie de vivre – gamine grin, jaunty bob, and all. Her legend had, in later years, taken on the air of melancholy that affects the image of so many people who guard the secrets of their private lives. But her parting shot, as she said, was not going to be ‘a narrative of feminine pain’. The narrative, packed with anecdotes and wry asides, lives up to its title: it is assembled like the dazzling patchwork of things and events that made up her life, career and style. It is an alternate iconography of beauty, and it is her legacy to Indian women and their modernity. The films, the labels and the corporations are there for us to define, but our identities can be independent of their existence, too. In Leela Naidu’s legend, as in the McLeish poem, beauty does not need to mean, but be.

Verve Trending

Sorry. No data so far.

us on Facebook to stay updated with the latest trends