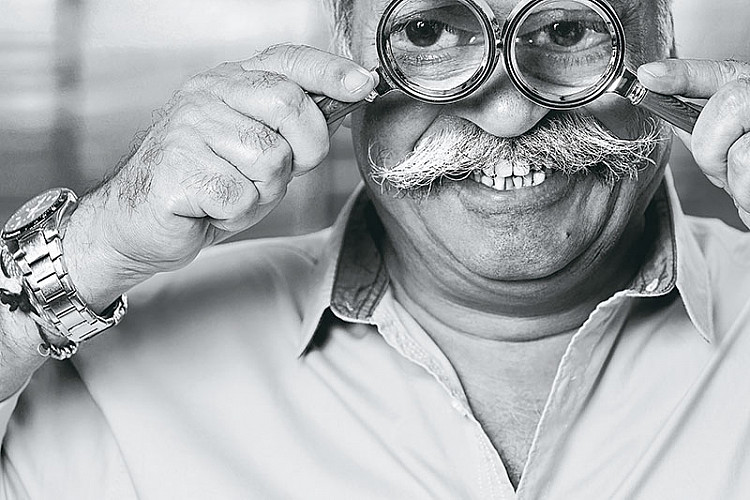

Piyush Pandey: The Man Behind the Mooch

I’m going to meet that moustache. It’s famous enough to be a visual shorthand for Piyush Pandey in the advertising world — an acknowledgement as much of its renown as of his legendary status in ad land. It lives up to its reputation — it is magnificent, luxuriant, outrageously masculine and fully worthy of its owner’s iconic status. I’m meeting the ad guru for the first time so, if I’m permitted a Pandeyism, I expect the man to be much like his mooch.

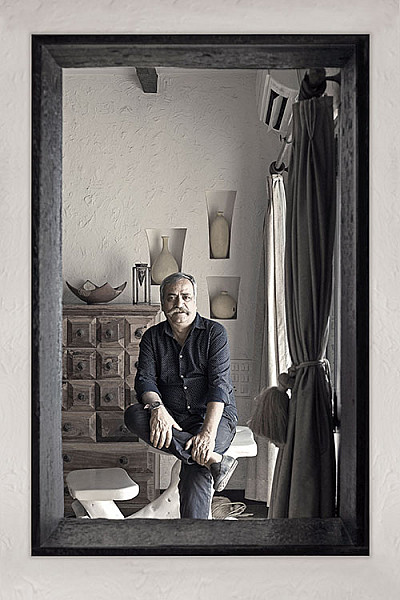

That he is — and isn’t. The gravelly voice, the high-octane rumble that reverberates through our conversation, the true-to-my-roots talk, the happily functional dress style — they’re all spot on. So is his home in Mumbai’s genteel, distinctly non-flashy, mid-town Shivaji Park; it is an airy seaside apartment with a magnificent view of the sea and the city’s latest landmark, the Bandra-Worli Sea Link. Its most formal area, the drawing room, has a comfortably lived-in feel that says much about Pandey and his wife, Nita, who designed it.

But, as we chat, the moustache fades from my visual focus and I see Pandey’s face in its entirety — it is a face that has lived life on its own terms. I hear the rhythms of India in his voice. I sense a humility that shares space comfortably with a throwaway arrogance. There is courtesy and compassion and, above all, respect

for his colleagues, compatriots and other cultures.

It could be no other way with this adman who stood Indian advertising on its head in the 1980s when he brought in an everyday Indian sensibility into an industry that was then influenced largely by Western ideas and aesthetics. That seamless intermingling of two worlds and cultures has propelled him to win “over 800 awards” and to the very heights of the ad world as executive chairman and national creative director, Ogilvy & Mather India.

Indeed, an entire chapter in his recently released memoir, Pandeymonium, is devoted to multiculturalism, a theme that is not only close to his heart, but integral to his work. I tell him I was particularly struck by one line in the chapter: ‘Multiculturalism is a statement of humility.’

The adman declares, “Look at India — it’s not a country, it’s a continent and it is so multicultural that if we do not learn to have some humility we will not exist. If I have to live in today’s world and if I have to communicate in it, I have to respect other cultures — it is as simple as that.”

Pandey learnt early, growing up in a family of 11, with his parents, brother and seven sisters. “If there are 10 other people in your family who like 10 different things, the idea of multiculturalism is already taking root, despite the fact that you come from the same culture,” he explains. “My sister Ila (Arun, the singer) would be singing folk songs and playing tabla beats on the door. My brother (Prasoon, also an immensely successful adman) would be practising debating. Somebody else would be painting. Each one of us brought something to the party that was unique. It was magic out there. I didn’t realise it then because I was too busy playing cricket. But it was in the air and today I’m making a living out of it.”

It must have been a happily noisy house. “A very noisy house,” he emphasises. “And it was a very small house, too. There was no way you could escape all those sounds and thank god for that, because those sounds are paying for my home today!”

Among those childhood sounds were those of Hindi poems and songs, courtesy his parents, memories of whom dot our conversation. One of Pandey’s great strengths has been that, unlike many of India’s urban elite, he thinks in his mother tongue. “Hindi was what we spoke at home; Hindi was what we emoted in. So Hindi comes most naturally to me, just as I’m sure Bengali comes naturally to Bengalis and so on. It’s just that some people choose to leave their own language behind, and that is the biggest mistake they make,” he says.

It was with a combination of his Hindi skills and an education at St. Xavier’s School, Jaipur and St. Stephen’s College, Delhi that Pandey stepped into the advertising industry in 1982. It was a time when the ad world was full of ‘suits’. But he lucked out with Ogilvy, as the agency is popularly called. “My bosses told me on day one: ‘We wear half-sleeved bush shirts because we think we are a Boy Scout agency and not a suited-booted one.’ So I was very comfortable there,” he chortles.

But there was a disconcerting discovery, too. “Everyone was reading English books, everyone was following the Black Book — a Bible of sorts in advertising, which shows the best ads in the world — and everyone was busy copying those ads. If I showed four of them to my mother, who was the buyer at that point of time, it would have taken her three days to understand them.”

He adds, laconically, “That has changed for the better now.” He doesn’t point out that much of that change happened because of him. Instead, he is quick to note that Ogilvy had already done ads like the Gale mein khich khich one for Vicks Cough Drops, which wove in Hindi lines and lyrics. “It wasn’t that Hindi was not used before I came in. But it was not used on the scale that it was in the mid ’80s, after I did Chal meri Luna.”

That was the campaign for Luna mopeds that catapulted Pandey to success. The line came, like so many of his memorable ones, from everyday life and language. “Chal meri Luna came from Chal mere ghode (Let’s step on it), a phrase which all of us have used as children,” he says.

But that wasn’t the first Hindi tag line he wrote. Pandey had joined the industry as a client servicing executive and was moved to the creative department only six years later. In those years, he confesses, he wrote some tag lines on the sly. “The first one was for Sunlight Detergent Powder. I remember it had Supriya Pathak saying Sunlight ki daam bas itni aur chamak…chamak dhoop si (Sunlight costs so little but gives you whiteness as bright as sunlight).”

After Chal meri Luna came the next blockbuster Dum lagake haisha, which he wrote for Fevicol, then an unglamorous ad account. Once more, it was a common phrase that struck gold. “All my lines have been taken from life,” he says. “Dum lagake haisha is what people say when they’re hauling something heavy or pulling a rope together, a collective effort has to be made and somebody gives that call so that everyone pulls at the same time. Is that a line I wrote? No. I took it from the people of India.”

Ditto for the election campaign he did for the BJP in 2014. “The slogan Janata maaf nahin karegi is the same as my telling a friend or a colleague, ‘Yaar, yeh mat karna, bhagwan maaf nahin karega’ (Buddy, don’t do this, god will never forgive you). Similarly, Acche din aane wale hain (Good days are round the corner) is a common phrase we use to cheer someone up. So I didn’t invent anything new for the BJP campaign.” (Of course, Acche din aane wale hain has boomeranged on the BJP government, but that’s a political story, saved for another time).

Back to Pandey who states, “Everything I’ve done by and large comes from people-speak. I’ve just changed the context and used it for something else.” Amazing how the simplest of lines can create such magic. But then, simplicity is often awfully hard to achieve, I remark. The adman has a different view. “Simplicity is magic. And sometimes magic is so close to you but you’re not willing to grab it; you think you have to try harder. Advertising is not rocket science; it’s a people’s business and easy-flowing copy is the best. Sometimes, one shouldn’t try too hard,” he argues.

This was a strategy that was clearly in action with the ad for Ponds Cold Cream which went ‘Woogli Woogli Woosh!’ The line came from a romantic moment when his wife Nita said it as she played with his cheeks; he just switched genders in the ads with the man doing the ‘Woogli’.

The result of this simplicity, he says, is that people will often tell him, “Oh, that’s so simple, I could have written it! Why didn’t I think of it?” He grins, “When they say that, I love it, I simply love it. That’s my victory! To think that only you can write a particular line is arrogance.”

The key question is, he believes, “Are you trying to impress or delight your audience? The choice is yours.”

It is an approach that has served him well across our borders, too. But how does he work with the everyday life and language of another country, another culture? He explains with a recent instance: “When I was called in to consult with the current Prime Minister of Sri Lanka, Ranil Wickremesinghe, earlier this year, the first thing I did was call in my Sri Lankan colleagues. Because I don’t understand their culture and I’d be an arrogant bastard if I went there and told them what to do. In all such cases, I keep telling those from the other country: ‘This line works in my culture; will it work in yours?’ I need their help. I have to practise humility.”

He’s had plenty of practice in India. It is, after all, what he has to do every time he works with a colleague who’s translating his Hindi line into another Indian language. How does one translate cultural and linguistic nuances within India? The answer winds back time a bit. “The starting point for me in any communication has always been the consumer. It can’t be me, it can’t be my product — it has to be the consumer and his need. So I try and speak his language. If it is Hindi, it happens to be my language too. But if I’m briefing a colleague who’s writing in, say, Tamil, I will spend a lot of time with him and always ask, ‘Is this the way you write or is this the way you speak — because there’s a huge difference. What are the phrases your mother used? What is the phrase that your doodhwala (milkman) uses? I’ve tried to do this all my life in advertising.”

The award-winning ad guru feels that the most satisfying campaign he has done has been for India’s Polio Eradication programme. Rewinding to the memorable achievement, Pandey says, “Last year on February 12, when India got its polio-free certification, Mr (Amitabh) Bachchan and I spoke at length and we said to each other that this was our greatest achievement. We played only one small part; many others, like the doctors, people in the field, the government and so many more people and agencies had much greater roles. But we were part of that team that helped free India of this disease that afflicts thousands of children. Nothing has made a bigger impact on me or meant more to me.”

Pandey believes that Indians are now more sensitive to the country’s linguistic and cultural diversity. He says, “Gone are the days when you could call anyone from South India a Madrasi. We’ve definitely made progress there.”

But what of the many religious and cultural clashes clouding the atmosphere today? Pandey takes a pragmatic view: “One, our country has thousands of years of history and that comes with baggage. Secondly, we are 1.2 billion people. We have people living in villages who hold certain beliefs and who have never been to a city in their lives. And there are people living in cities who haven’t bothered to visit a village in their lives. So, to imagine that everyone will live with an open mind is living in Utopia.”

But shouldn’t we strive for Utopia? “Of course, we should. But will it ever happen to the fullest, will it ever be, 100 per cent? I doubt it. What we can do is to be as open as we can, to open as many doors as we can.”

As good a point as any to end on, I think. I’ve forgotten all about that moustache as I take a good last look at the morning sea and its Sea Link.

Related posts from Verve:

Verve Trending

Sorry. No data so far.

us on Facebook to stay updated with the latest trends