Spaces That Travel

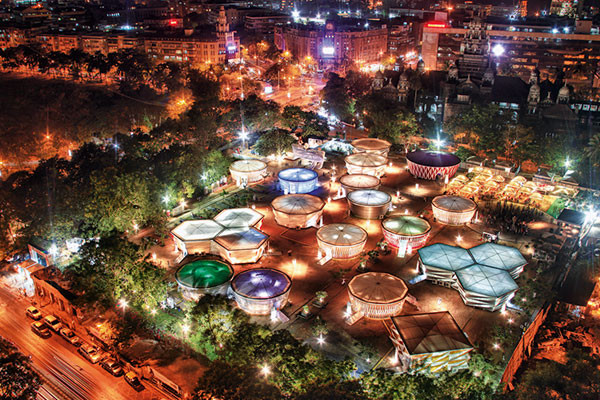

In the street adjacent to the Cross Maidan grounds in downtown Mumbai, the majestic crimson and white structures formed a backdrop to Churchgate Station and the almost-setting sun. Two hours later, the structures were lit up in a striking array of colours. Yellow. Purple. Blue. These pavillions were a part of the Indo-German Mela conceptualised by renowned international artist Markus Heinsdorff. I knew that name. I had seen the images of his bamboo structures at the Expo 2010 on an email sent by a friend from Shanghai.

Some days later, awaiting me and a photographer at a downtown hotel’s lobby was this over six-feet-tall, powerfully-built man who apparently could barely stand the city’s humidity. He was sweating profusely. He apologised, “I am sorry, I am not used to your weather. But don’t go by this shirt, I have a spare one for your shoot!

Heinsdorff got working on the mela project a year ago when German officials invited him to design the pavillions. “After Expo 2010 in China, India was a natural progression. They didn’t give me much time but I am glad I was given the opportunity. Before starting work, I went to the Indian library in Germany to study Indian fashion, design and history. Exquisite. India is so colourful. It’s a pleasure to do something like this here for my country.”

During his research, Heinsdorff stumbled upon an image of an elephant with an extremely ornate caparison. “I was fascinated by the sheer sight of it. Even more when I learnt that the elements used to decorate the saddle of an elephant can actually fill an entire cricket ground. I was spellbound. Ceremonies and processions I had known of but this was something else. I decided to use caparison as the leitmotif of the theme.”

The idea was to create a mobile space that could travel throughout India with the mela. “The thought behind mobile space is that we can go from A to B and while the concept of animal, nature, design and display already exists, the idea was to make it relevant to our time.” Heinsdorff decided to make modern and hi-tech gemstone-shaped structures taking their hues from rubies and corals. They were manufactured in India. “Call them tents if you want. Anyway tents are a big part of your tradition – the tents in the deserts or marriage tents – they are lovely. I love to use new ideas to shock people a little bit and make them say…oh boy…what happened here! In a good way, of course.”

Heinsdorff constantly thinks of ways to save energy so that we can handle the future better. “Most urban cities are a replica of one another. But when I look outside the window of my hotel room in Mumbai, I am glad I am not looking at a city that’s too metropolitan. I am able to recognise it. It’s the same with Delhi and Kolkata – I see glimpses of Asia in them. Besides the style of architecture, the air, the clouds, the birds are all so unique to the city. They tell me that I am not in Shanghai.”

Conducting workshops in several Asian cities, Heinsdorff feels that pollution is the ugliest part of these towns and that several old buildings are losing their faces. “Find your own style, out of your own culture. Don’t copy. If you look at modern cities in China, they build high-rise buildings overnight. It’s scary. It’s important to do things slowly. India is starting now. Things are getting better. The way for the future is being made now. It’s the best time to introspect on how we need to design the future in a way that’s human and environment-friendly. No one likes to stay in slums in sub-human conditions. No one wants to open their windows to find a thousand cars increasing noise and air pollution.”

For him, Mumbai is like a living body with a mix of good and ugly structures and some great public spaces but ask him what he thinks of the city’s public art and he replies with a straight face, “Public art? In Mumbai? Where’s that?” There’s silence. Then he quickly responds, “Public art is used for decoration but I don’t miss it in this city. Your public art is your people. One day I have a taxi driver who is a Muslim, the other day there is someone from another part of the country, someday there is a local – it’s so colourful and ethnic.”

Heinsdorff rues that most architects worry about projects being cost-efficient without thinking about how environment-efficient they are. “It’s a pity but it’s a worldwide problem and we have to work on this.” When he designs a space he designs it for two phases – one for the day time, one for the night. “In the day, you feel there is an extremely modern structure that’s adding drama to the skyline of the city. By night, the lights make these structures look like scenery from a countryside. Like a movie.”

As we step out of the hotel to cross the street over to the maidan for the shoot, Heinsdorff is fearless of the oncoming traffic. He is not claustrophobic about crowds. He daringly crosses over the street, not using the zebra crossing, just like us. In the last one year, he has travelled several times in and out of the country and has fallen in love with Mumbai and the Indian naan. “It is one of the few countries worldwide that has such a wide variety of architecture. I would love to do a portrait of the city.”

As the photographer prepares for the shot, Heinsdorff presents a favourite idea of his, that we should be able to change the structure of our homes as we change our wardrobes! “Why can’t we take our home with us? Fabrics give us the possibility to do something like this.”

His affinity for textiles comes from his grandmother who was a weaving master. “It was a huge part of my upbringing. I truly feel there is so much more that we can do with fabric and space. Think lightweight homes or moving holiday homes, like in the desert. It’s such a sustainable way of doing it. It’s a nice bridge between fashion and space. Maybe it’s the form for architecture in the future. And maybe it’s a long experiment…but then, I’m in a good mood right now, so let’s get going on this,” he says, striking a confident pose against the crimson-striped pavilion that he has so artfully created.

Related posts from Verve:

Verve Trending

Sorry. No data so far.

us on Facebook to stay updated with the latest trends