Economies Of Style

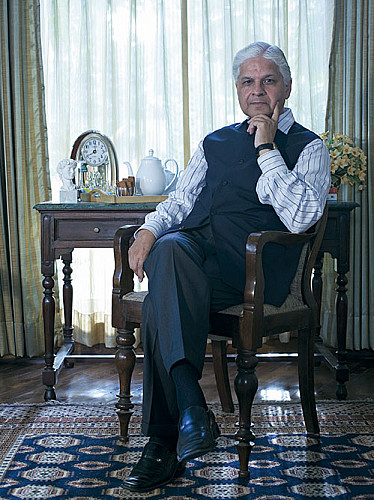

Well past midday, Dr Ashwani Kumar is immaculately dressed in a creaseless navy blue Nehru waistcoat, a silk scarf folded neatly into the breast pocket. If appearance, image and aura are anything to go by, then his emanates a polished cleanliness. Even the air about him seems to purify as he settles down on the neighbouring couch. “It is extremely important,” Kumar begins, “to be correctly and appropriately attired depending upon how others perceive you. Certainly, dress is a mode of communication and expression.” On his first trip to Paris, aged 28, he was made aware that he might possess a quality called ‘good taste’. “I had just finished some time in Oxford as a young lawyer. I was observing a parade on the Champs Élysées and commenting on the jewellery and clothes I saw, oblivious to the fact that a lady was sitting close to us and she was working for Christian Dior. After we got up, she said to my companion, ‘Your friend has good taste’. I don’t even know if she was joking.” On most days, you will find him wearing a Nehru jacket. During summer it’s strictly khadi, “stitched in the traditional style of a kurta pyjama from Punjab”, the state from which he is elected. Sometimes he wears a Pathani suit, which he says reminds him of the North West Frontier province in pre-partition days. And when abroad the bandhgala or a business suit. His wardrobe contains four consistent colour blocks: charcoal grey, navy blue, black and white.

Conversely, his professional roles are varied and req–uire frequent role swapping and hat changing. From a parliamentarian trying to understand and communicate the sensitivities of the people, to his duties as a Minister of State for Industry, helping to form and implement policy, working on intellectual property law and regime, in addition to being actively engaged in promoting industrial and investment potential in India, both domestically and abroad. To be in his position is “challenging as well as rewarding” he says, “in an era of globalisation, when India has emerged as the tenth trillion dollar economy of the world, with the possibility of becoming the third largest economy by 2035”. In September last year Kumar delivered a lecture at Harvard University entitled, Inclusivist Growth and Economic Reforms: The Challenges of India’s Pluralist Democracy. “From those exalted corridors of power I then had to go back to my constituency in Punjab to understand the pulse of the people. I needed to explain to the ordinary man what the nuclear deal would do for him, he had no idea. He is concerned about why his buffalo was stolen. I consider myself privileged to be able to speak in different languages and idioms because the essence of democratic politics is about this sort of fusion. The fusion of immediate local concerns with the larger concerns of the nation. In a sense my life is an unending journey between two extreme poles of activity that are at different ends of the political spectrum. Which is not always an easy experience. It is essentially a challenge of communication, a multi-dimensional endeavour.”

Making the inaugural address at the launch of the FICCI Lifestyle Forum, Kumar highlighted the fact that India has a competitive advantage where culture and craft, design and creativity, textiles and gems have been our traditional heritage. Adding that there is significant employment generation potential and a huge market globally and domestically. “What we need to do is build globally acceptable Indian brands. And that requires the urgent addressing of skill upgradation. We have vastly talented people who just require intense training in fine-tuning to be competitive in price, quality and logistics,” he feels. “The government will assist to achieve standards of excellence and competitiveness, which alone will guarantee the sustainability of a business model.” The FICCI forum will also encourage proposals for craft centres, SEZs in jewellery and institutes in high-end fashion. All the while, “needing growth to be inclusivist, making sure that GDP increase makes sense for the have-nots”.

If the success of a politician’s job depends on how effectively he can create communication channels across the political spectrum here and also represent us abroad, then the luxury industry is fortunate to have two of the Congress party’s most articulate men. The Minister of Commerce and Industry Shri Kamal Nath and Dr Ashwani Kumar, whose active political association with the party dates back to 1977. These two men can always be called upon to distill, summarise and elucidate knotty laws and complex economics. “That is what people say is my strongest point. I think a minister’s job on the political side is essentially one of communication.” Take the ubiquitous words ‘lifestyle’ and ‘luxury’, both currently overused and over exposed to the point of hollowness. “Lifestyle,” Dr Kumar explains poetically, “has to be understood within the frame work of culture as an endless journey of civilisation. The brocade work of Benares, the texture of a Kashmiri Jamavar and pashmina, the hand-embroidered Phulkari of Punjab, these weaves are the weaves of culture which have been handed down through the artisans and become a part of life. The richness of colour and weave of cloth and texture in a way represent a fusion of generations of art. These are luxuries. Woven into the culture of India. It’s simultaneously a pleasure, an occupation and a money making enterprise. So, the real art and culture is a dialectal relationship between man’s daily existence, the art he produces and gets defined by. Corporatisation means we take our art and culture global and the first requirement of a successful designer here is his ability to envision something that people can appreciate, as opposed to images that only appeal to him. That is why Manish Arora is successful. He’s found a rhythmic fusion of colour, cut and culture.”

When asked to define luxury, especially in a country with a huge disparity between rich and poor he says, “On one level luxury is about feeling good about yourself, what you eat, what you wear and your state of physical and mental fitness. On another level, luxury is about comfort. To enable one to perform to one’s optimal capacity what one must do. But, the most enduring luxury is that of a spirited existence. It has unfortunately become a luxury in a world where fleeting thoughts and immediate actions for survival have become the order of the day. I would pray that I have the luxury of enough opportunity and time to reflect and to meditate and to enjoy the smaller pleasures of life. Which are all free.”

This mix of lyricism and legal eagle lucidity is characteristic of the 56-year-old son of a freedom fighter who reads eight newspapers every morning and can drop Urdu shairies in mid speech (a hobby he gleaned from his grandfather, an untutored scholar of the language). The framed academic achievements that adorn his walls are many. This politician holds a doctorate in law and masters in philosophy in international law, after studying at St Stephen’s College, the University of Delhi and Jawaharlal Nehru University. Because of his considerable intellectual powers as a lawyer he was appointed Additional Solicitor General of India in 1990 at the proud age of 37 and subsequently elected to the Rajya Sabha in 2002. The following year he published a book, Law, Ideas and Ideology in Politics: Perspectives of an Activist; he served as Chairman of the Vichar Vibhag (the Congress party’s intellectual cell) and on several committees related to energy, finance, information technologies and commerce; did a turn as party spokesperson and finally became a minister of state in February 2006.

It’s almost too perfect. The laurels, the career graph, the perfectly precise political sound bytes, the wrinkle-free suit and neatly combed hair. A lawyer, politician, minister and culture aficionado – he’s practically made an art of public service and has an image to match. “The only art is never say what you don’t want to say.” So we ask him if he ever feels unnatural and constrained, working a job where constantly censoring a lot of his more fleeting thoughts is a requisite? “I’m at heart a rebel so yes one of the most difficult jobs is to weigh every word that is spoken, to err on the side of caution. But it’s an inherent requirement of the job along with the invasion of your private sphere. Sometimes I feel like I am essentially a very private person in a very public job.”

Related posts from Verve:

Verve Trending

Sorry. No data so far.

us on Facebook to stay updated with the latest trends