Keeper of Memories

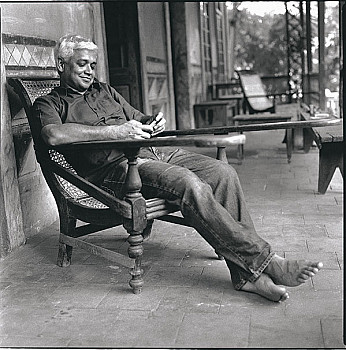

Sinking into the beige couch of his sea-facing room, I feel Amitav Ghosh’s Zen-like presence calm my nerves much as opium did Hukam Singh the afeemkhor’s in Ghosh’s latest work Sea of Poppies. So, I decided to take this moment to prod him about his equation with his new publisher. Penguin, contrary to expectations, wasn’t the big bad publishing giant of capitalistic fairy tales. Having previously published with the late Ravi Dayal, he tells me how pleasantly surprised he was by Penguin’s tight-knit community. “I think the one thing that has been missing in India has been a systematic attempt to grow a readership and that’s something you can’t do as a writer. You need an organisation to do that, and as a writer it’s your duty to cooperate!”

With a host of critically acclaimed works backing him, his readership has been secure for a while and Ghosh has no need to rue its rather nebulous state in India but the storyteller isn’t restricted by parochial notions of self-interest. He encourages me to read Mukul Kesava’s The Ugliness of the Indian Male a book he has just finished, and tells me about a work by a Burmese writer sent to him for a blurb – the way he gets most of his books these days – he admits, chuckling.

Having read Sea of Poppies cover to cover and returned often to passages like Deeti’s journey into the opium factory in search of her incapacitated husband or the zamindar, Raja Neel Ratan’s trial, I obviously had to know what set him off on this, the first part of his proposed trilogy. As it turns out, the seeds for the opium wars that consume this series had their genesis in the migrations we first encountered in The Glass Palace.

“I became interested in the migration out of India and wanted to write about the early years of it which go back to the 1830s.” His characters, often rootless and painfully aware of the fact, inhabit a world in which their lives and the possibility of social mobility are decided not by themselves or their social mores but an alien empire, which is never to say they lack agency. “I always think my characters are struggling against their destiny and in some way they’re remaking their destiny. That’s what excites me, the idea of people creating their own destiny and in some way, that is what migration is about.”

Having constantly moved around in his formative years and still dividing his time between Kolkata, Brooklyn and Goa one can understand where this preoccupation stems from. But while that sounds reductive and even a little obvious, he adds, “It’s really a process by which people seize control of their own lives. It’s a process through which people who are otherwise complete slaves to circumstance finally decide: ‘No I’m going to change my circumstance,’ and that process of refashioning and reinvention is what interests me.”

His social and anthropological bent clearly make his writing contextual but the bearing that these macrocosmic events have on the lives of his extremely resilient characters demand a lot of research which interests him as well. This process of reading and unearthing history also takes him travelling across the world. The Ibis trilogy has already taken him to Mauritius and China where he spent a lot of his time cooped up in libraries and museums and also fraternizing with locals.

From the recesses of Ghosh’s literary history I recall him having said, ‘the issue of how the past is to be remembered is at the heart of The Glass Palace,’ and it is evident that this belief holds true of his new work too. As he sits back, sipping his tea, he tells me about a ship depot in Mauritius which harboured ships that carried indentured labour that has been made into a national monument and which is now pushing to become a UNESCO monument. He wistfully shakes his head adding, “These things are treated with great attention, care and respect in some places but if you think of the majority of migrants who left from the depot in Kolkata, there’s no trace of it. It’s just vanished! And it’s vanished not because something important has been built there but because it has become a slum. If the city were to build a monument there to memorialise it, just from an economic standpoint, think of the number of people who would come visit. This was one of the world’s great migrations!”

His ruminations recall Baboo Nob Kissin, the laughable yet pathetic agent who arranges for indentured labourers but also sets up a camp as a temporary refuge for them in Sea of Poppies. Pondering on the characters and rhetoric of Sea of Poppies Ghosh insists that there’s some of the same callousness in each of us. He refers to the period of the opium wars alternately as a “grave question mark in India’s past”, “an erasing of our consciousness” and “a weird remembering of history”. And it’s this blank tabula rasa, this manufacturing of a consensually forgetful history that he tries to set right in his works.

Despite its rather intimidating dimensions Sea of Poppies needn’t be a stow away for a perfect cruise. It’s interesting then that his one dissatisfaction with his works is their brevity, shocking to anyone who has considered his opus. “I felt I could have lingered on or spread out more and doing a trilogy really gives me the space to do that.” It’s also why he finds writing so engaging. “It’s all improvised, there’s nothing in it that is not…. Every day when you sit down at your desk you have to put on a performance and the performance is just to yourself but it’s in the same way that an actor comes out and improvises. You’re really just making it all up every single day. You’re squeezing your brain like an orange, every day I feel like I’ve just squeezed my brain,” he chortles.

His passion for writing and for language seem at par with one another. As we start parleying on etymologies and the importance of the plurality of languages, cultures and ethnicity, he sits up – a little troubled for the first time during the interview. “The idea that people have, that your relationship with the language you write in has to be a comfortable one, is a misplaced idea. I don’t see why that should be. One’s relationship with every language should be difficult because it’s out of that tension that something creative emerges.”

Giving the conversation a sense of immediacy he relates it to the situation in Iraq. Launching into a diatribe on the way language is used to render political deeds benign he argues, “When you start rooting identity in language or in any one thing, you create a sense of identity that becomes very exclusionary. Not only is it morally wrong to create that sense of exclusion it’s also politically, culturally and economically suicidal.”

Economic concerns do bring me to the possibility of cinematic adaptations. Lyrically spun together it’s already got Bollywood big-wigs vying for exclusive rights. I personally think adaptations would be unfeasible, a thought given credence by the fact that directors and producers have often dropped the cinematic ball on these projects. But I also fear art directors will mess up the cinematography, characters will be cut for want of time and melodramatic thespians will cause sheer overkill. Ghosh though, is unperturbed by creative differences with moviemakers. His focus now is his sequel, surely lying somewhere beyond the sea….

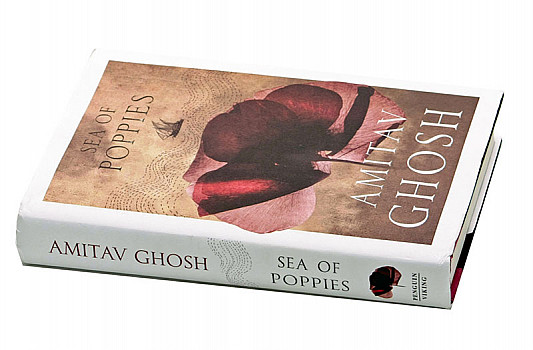

FLOATING HISTORY

Sea of Poppies

(Penguin/Viking)

In the tradition of Dickens’ serialised fiction comes Sea of Poppies which closely mires the lives of its characters across all strata of society. From the widowed Deeti and leviathan Kalua, to zamindars like Neel and colonialists like the Burnhams, from mulatto seafarers like Zachary Reid to libertines like Paulette and a whole host of lascars and girmityas (indentured labourers) who populate the first of the Ibis trilogy, Ghosh creates characters that promise to be sought out in sequels. Centring on the opium wars that have long been forgotten, Ghosh once again brings attention to issues that have been brushed under the metaphorical carpet. While he conjures from floating history, characters that struggle against or conspire with circumstances that invariably trickle down and have ramifications on the fringes of society, he also puts us at unease with our own history. Sea of Poppies forces us to confront our complicity in colonialism and questions the silence of consent that is pertinent to neo-colonial practices that continue today. While some of the writing seems a little incredulous, the appropriation of Indian languages by the English for instance or even a little melodramatic none manage to surmount the epic tale that’s only in its nascency. It isn’t in quest of novelty that one should reach for this tome, though it certainly can be found here. It is to discover what Ghosh does best – remember forgotten histories.

Related posts from Verve:

Verve Trending

Sorry. No data so far.

us on Facebook to stay updated with the latest trends