Discover The Poetry In The Colourful Threadwork of Phulkari

Of Poetry and Punjab

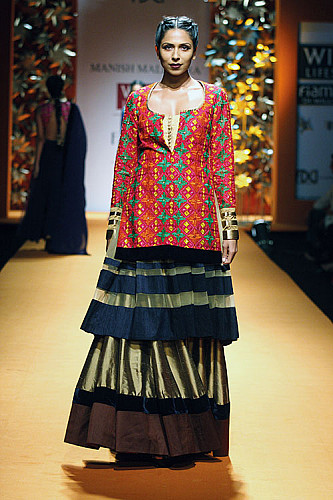

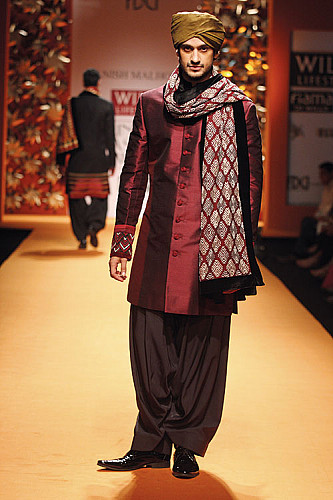

“There is an increasing impetus in fashion to revive the conversation about heritage. The Philadelphia Museum of Art has recently announced an exhibit on phulkari. It certainly brings a sense of gratification to see one of our crafts being recognised on a global platform,” says Manish Malhotra, who presented his Threads of Emotion phulkari collection at Wills Lifestyle India Fashion Week 2013 and whose apparel is currently on display at the Museum’s Phulkari: The Embroidered Textiles of Punjab from the Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection exhibit.

It was in the 18th century that the word first found mention in Waris Shah’s epic poem on tragic lovebirds Heer and Ranjha, as part of Heer’s trousseau. Literally translating to ‘flower work’, phulkari has since been intertwined with the customs of Punjab. In olden days, when a girl was born, her maternal grandmother would start stitching a chope odhini (a type of dupatta), which would be presented to her on her wedding day.

Routines and Rituals

The craft was undertaken by the women of the household, who got together in their leisure time to indulge in hours of undisturbed stitching. Because they embroidered as a hobby, the sainchi phulkaris depicted motifs of routine village life such as men ploughing the fields and women working the charkha. More elaborate baghs were produced as dowry during marriages while the darshan dwar phulkaris were presented as offerings at gurdwaras. The embroidery was often a medium of expression too, with themes of morality and superstition being explored.

Initially tied to religious traditions, phulkari began to deteriorate under the influence of the Raj, when British firms began procuring orders from Europe and America to supply embroidery on a commercial scale. With international markets dictating designs and colour schemes, garish iterations were produced.

Fine Eye and Steady Hand

Since the technique does not involve outlining the design beforehand (save for the chope), it was vital that the fabric used be coarse enough to facilitate an easy counting of the threads, which controlled the pattern. Original phulkari was done on hand-spun khaddar on the reverse side of the fabric. The cloth was then locally dyed in hues of rust red, madder, indigo and black, although elderly women and widows preferred plain white khaddars called thirma. Finally, soft, untwisted silk floss called pat in golden yellow, crimson, orange, brown, green, blue, violet and white was used to begin the process. The darning stitch was most commonly used vertically, horizontally and diagonally in short and long strokes to create the intricate geometric patterns.

Inspired by its colourful heritage, Malhotra couldn’t resist dedicating an entire collection to the embroidery, working it effortlessly into clothing for both men and women. “Besides offering a palette to work with, colours have always enamoured me with the deeper meaning that they hold in our culture. Phulkari gave me the chance to work with the entire spectrum in a single collection,” he says.

In its detailed process also lies its challenge. Explains Malhotra, who designed Kareena Kapoor Khan’s iconic Jab We Met salwar kameez, “This is an art form that requires meticulous attention to detail and a monastic sense of discipline. The manner in which the colours flow together through the thread-work is only achieved by a fine eye and steady hand.” What’s more, Malhotra says that it takes an average of three months to complete a garment because “each is created by a single artisan in order to retain uniformity in design”.

The Road Ahead

While Bollywood movies like Tanu Weds Manu and Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi have given the embroidery its share of attention, it is yet to be embraced in the same way as other heritage techniques. Malhotra says, “Our sartorial history offers a glimpse into how we evolved. So, it is a matter of great prestige that we preserve and nurture our textile and design legacy.” He remains optimistic about its appeal and asserts, “The details that define it make it versatile. From flowy dupattas to saris and modern silhouettes like cigarette pants and jackets, it can easily be transposed onto the modern wardrobe. There are few techniques that look as great on a Western silhouette as they do on a traditional one; phulkari is one of them,” he asserts.

Modern-day brands like Aiyana by Umeed Foundation, Bandhini Home, Craftsvilla and Jaypore do retail phulkari clutches, juttis and bed linens, but many rue this dilution. Malhotra however insists that accessibility is key to retaining relevance. “Saying that a craft must be consumed in the manner it was centuries ago is impractical. Presenting it in varied forms and silhouettes through a modern design lens is imperative to retain its magic,” he insists.

Care For Your Wear

“As with anything crafted with such fine detail, phulkari outfits require great care. Resham threads tend to break with exposure to strong elements; so, pack your garments in thin tissue to keep them safe.”

Related posts from Verve:

Verve Trending

Sorry. No data so far.

us on Facebook to stay updated with the latest trends