My Mother’s Missiles

Ananti sat on two cushions in the half shade of the balcony and rolled a piece of cardboard into a tight cone. She folded its tip to keep it from unwinding. Then she filled it with a fistful of ash, which she collected from the clay stove in the kitchen and stored in small mounds around the stem of the potted curry leaf tree that stood next to her. She pushed the pot into the corner as far as it would go, but still the salty breeze from Juhu Beach would blow the fragile grey dunes away every few days. To Ananti, the air in Bombay smelled of petrol and cheap liquor these days. India had just celebrated the tenth anniversary of its independence.

“Aradhana!” Two fingers coated the inside surface of the cone with ash in quick strokes. Ananti propped it against the wall. “O, Aradhana!”

A girl of 12 or 13 scampered through the doorway and sat cross-legged on the mat in front of her mother.

“What took you so long? And why are you laughing like that? Better to show your bare arse than to laugh with no shame.”

Aradhana stopped trying to hide her giggles. “Bhautik says the English use paper – rolled over a tube! – to wipe…”

“Can’t you keep anything to yourself?” Bhautik had been listening to his mother and sister from inside the room.

Ananti stopped undoing her daughter’s plait. “Chup! I don’t want such dirty talk in this house. I told your father nothing good would come from sending you to an English school. But does anyone listen to me? No one listens to me. When I was a girl, nobody sent me to any school, but you people think not even Gujarati is good enough for you.” The tips of Ananti’s fingers moved swiftly over Aradhana’s scalp as she parted her hair into neat shafts, from which she plucked the lice, dropping them into the cone of ash. Once inside, they would be unable to escape.

Ananti’s husband, Suresh, had secured a job as a station master just as Aradhana had started school. They had moved out of their shared accommodation into the two-room flat in the Railway Colony. Their previous quarters at the chawl had been predominantly Gujarati and from the same caste as theirs. Here, with Railways being a transferrable post, their neighbours came from all over, even as far as Kerala. The colony was located in the neighbourhood of a gauthan, so it was largely Christian. Suresh had heard from his neighbours how their children were hired by the hotels and offices on Marine Drive and Cuffe Parade for salaries twice his own. That was when Suresh had started saying that the children should go to St. Joseph’s, which was just a five-minute walk further than Goklibai Elementary School.

“Look, it’s Ardonna’s brother,” Rosie and Mary would say whenever Bhautik walked past them on their way home from school. Bhautik liked how they pronounced his sister’s name, though the colony boys made fun of the Christian girls, who used every opportunity to anglicise words and manners. It was not until recently that it began to dawn on him that they barely knew more grammar than he now did since joining the English school. Bhautik bit his lip and smiled at the thought of the dialogue the older local boys would recite whenever gauthan girls walked past:

“Where go?”

“Church go!”

“Why go?”

“Prayer go!”

But when Rosie and Mary came to the flat in the late afternoons to pick up Aradhana, Bhautik would step out onto the balcony just as the three girls sauntered down the lane towards the beach, laughing and shoving each other playfully, their arms hooked into one another.

Ananti searched Aradhana’s head one more time with her frisking fingers before rubbing the smelly sharifa seed paste into her scalp and weaving her hair back into a braid. The girl returned inside. Ananti picked up the cone and walked up to the edge of the small balcony. The lice stepped over each other in a vain attempt to climb the slippery, ashen wall. She leaned forward to make sure no one was approaching. Then she threw the crawling cone into the adjacent balcony with one practised thrust so that the lice, unwanted but not to be deprived of a livelihood, might thrive on a neighbour’s scalp.

Aradhana filled the water tumbler and poured it over her mother’s plants that lined the balcony. Winter was slowly approaching, and water was always short. The girl took her time moistening the earth in each pot just enough so that nothing would seep out of the holes at their base. Then she dipped her hand into the tumbler and sprinkled water over the dusty leaves until the plants gleamed like seaweed washed ashore.

Her mother had been calling her. She would say she had not heard. Aradhana smiled to herself. For a few days, lies and excuses would come more or less for free in this house. Her mother was menstruating and was not allowed to touch anyone or enter the kitchen during that time. Though Aradhana had to cook for the whole family on those days, she much preferred that to her mother’s firm hand, ever-ready to slap, hit or pinch.

Aradhana had experienced her first menstruation just a few weeks before. She had awoken in the middle of the night from a stomach pain she did not recognise. She felt the wet stain at the base of her spine where the fabric clung to her skin as she turned from lying on her back to curling up on her side. The next evening her mother had pulled out the jute mattress from underneath the bed for Aradhana to sleep on that night. The coarse material had bitten the girl’s hand as she stroked its surface.

“At least you won’t need a mosquito net tonight because you’ll be stung from below,” Bhautik had teased.

Aradhana had shot her brother a furious glance. “I’m not sleeping here.”

There had been a scene – Aradhana had cried. Then her mother had cried. Voices were raised. Bhautik gathered his textbooks and took refuge at the neighbours’. Suresh, umpire of the family with his own set of rules, ordered his wife to shut her mouth.

Aradhana had used the quiet to press her point: “It’s not fair, Bapuji! Bhautik never has to sleep on it. You don’t have to sleep on it. Rosie and Mary sleep in their own beds every day of the year. Why shouldn’t I? If Mamma wants to sleep on the jute mattress she can do that, but I won’t. I refuse!”

Aradhana wasn’t done, but Suresh cut his daughter off.

“You’ve said a lot tonight and I have heard enough.”

“But Bapuji –”

“Sleep in your own bed for all I care, but spare me your speeches. Is that all they teach you at your English school?”

Aradhana thought about that night as she gazed from the freshly-watered plants down into their lane. Her mother’s calls were more insistent now. Aradhana left the balcony and stepped into her parents’ bedroom, where Ananti was squatting on the jute mattress beside the bed. Before Aradhana could say anything, a small tub of glue flew towards her and hit her on the shoulder.

“I won’t even let you open your mouth to make a liar of yourself! I know you heard me!”

“I must have got distracted.” Aradhana replaced the glue on her father’s desk.

“Why haven’t you started dinner yet?” her mother demanded.

“I was just about to when I heard you call.”

Sensing trouble, Bhautik helped with the cooking. Armed with a comb and box of hairpins from the bedroom, Ananti positioned herself by the threshold of the door – the kitchen was out of bounds for her.

Bhautik first cut the gourd into finger-thick slices and then into squares. Aradhana chopped a tomato. She heated up oil in a kadhai. Deciding it was hot enough, she gathered a heaping pinch of cumin seeds in her fingers and dropped them into the oil. They turned dark brown, but failed to swell up and dart around. The box of hairpins exploded against Aradhana’s spine.

“Ruined our dinner! How many times have I told you to wait till the oil is hot before throwing in the masala? Do you hear sputtering? No. There should be sputtering! But the oil is not hot, so how could the jeera sputter?”

The black pins lay strewn on the kitchen floor. One or two stuck to Aradhana’s heel as she shifted her weight. Without a word or glance at her mother, Aradhana poured the oil with the softened cumin seeds into the drain in the corner of the kitchen floor.

“Wasting, wasting, wasting! Why? Because nobody wants to listen to me. Because my English-speaking children think I’m a fool.”

While Aradhana prepared the vegetable, Bhautik started rolling out balls of dough into thin parathas. He was not as experienced as his sister in this task, and his parathas took on complicated geometrical shapes. He was expecting the comb to hit him from the beginning, but Ananti waited until she found him lost in thought rolling a paratha that she did not know reminded him of the map of their very own Mother India (he had just seen the eponymous picture at Radheshyam Talkies and was planning to see it again on the weekend), a slab of dough in the vague form of a diamond. He was lengthening the peninsula to accommodate the southern states when the comb struck his upper arm and bounced off, narrowly missing the kadhai and the fire underneath it in its path to the floor.

“You think this is some sort of school project? Playing with food! Problem of plenty. I wish I had grown up with that problem.” Ananti disappeared into the bedroom.

“Just pick up the comb and the pins,” Aradhana instructed her brother as she lifted the small steel thali covering the vegetables with a rag and stirred them, probing their toughness with a spoon.

“For what? She’s only gone to get more.”

“More what?” Aradhana was only half listening. She was thinking about whether she might see Rosie later that evening. She lived in the same building, and Aradhana wanted to show off the watercolour painting she had made of the balcony, featuring her mother combing through her hair in the sunshine, both their faces smiling at the onlooker beyond the frame as if posing for a photograph. At the very end Aradhana had painted her mother’s free hand holding an oversized cone of ash like a bouquet of flowers.

“More missiles, of course.”

The siblings looked at each other and smiled.

“Mamma’s missiles,” Aradhana said to her brother, deciding that that’s what she would name her painting: My Mother’s Missiles.

That evening Suresh returned home later than usual. While she reheated the food, Aradhana laid out three mats on the kitchen floor and placed a thali and katori at the centre of each one. She ladled the sabzi into the bowls. Suresh and Aradhana sat down in front of their food and ate. Bhautik, always in a hurry to go out, squatted before his thali.

“Why are you eating like an Uzbek?” Suresh said. “Sit properly.”

“Aren’t you going to complain about Bhautik’s parathas?” Ananti was standing in the doorframe. “You always do when I make them and mine at least are the right shape.”

Suresh looked at his son, sitting cross-legged on the floor now, the tomatoey juice from the gourd running down the fingers of his right hand onto the steel thali.

“I’m used to the food in this house,” he said and sighed.

Aradhana brought out the rice and spooned portions of it onto the thalis, now marked with traces of oil and slivers of vegetable. She scooped the yellow dal on top of the white mounds and sat down to finish her own dinner.

Ananti retreated into the bedroom. She spoke loud enough for the family to hear every word: “God forbid he should come home and tell his wife why he was late. But the wife is stupid, so she must not be treated with respect, because how dare she have a peaceful evening for once.”

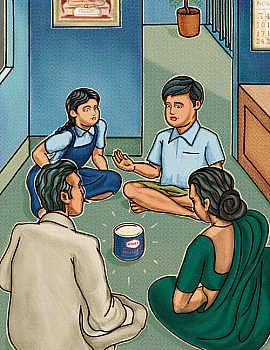

After Ananti had eaten from the thali placed in front of her by her daughter, Suresh gathered his family around him on the chattai covering the floor of the bedroom. He waited for a moment while his children stopped fidgeting and his wife’s gaze grew more intent.

“Today I saved a man’s livelihood. That was the reason I was late.” Suresh looked at his family. “To thank me, he gave me this.” He took out a squat, cylindrical tin from his satchel and placed it at the centre of their circle. Big red letters adorned the blue background.

“But tell us what happened first,” Ananti said, keeping her eyes on the tin that her children had already picked up for inspection.

Suresh recounted how he had found a thick notebook filled to the last page with English scribbles underneath one of the berths of the train when it had pulled into his station. Since he had no use for such a thing, he had taken it to the station supervisor where an agitated Englishman was slandering several of his cabin mates as thieves and rogues. On seeing the precious object in the station master’s hand, the Englishman’s tone changed.

“It’s a book in the making, you see, about this wonderful country of yours and the progress made by the nation in its first ten years of democratic government.” He spoke in accented Hindi and praised Suresh to the supervisor for his ‘Gandhian integrity’. The Englishman had opened his suitcase on the platform floor, grey with dirt hardened by spit and cheap disinfectant, searching through its contents. When he had stood up again, he was holding the blue tin.

“At least he didn’t give you back the used-up diary,” Aradhana said, remembering the pristine, forbiddingly expensive sketchbook she had held in her hand at the stationery shop some days before.

“Maybe it contains something valuable,” Bhautik said, taking control of the tin. He rapped his knuckles on the surfaces; it sounded solid.

Aradhana imitated her brother’s voice. “Maybe it’s an English seashell filled with pearls.” She laughed and ran her forefinger over the smooth metal, feeling the corrugations between the cobalt-blue background and the bright red of the writing. “It’s pretty like a seashell,” she admitted.

Ananti looked again at the tin, the contours of the letters sharp and perfect. There was nothing like it in her household and she felt the urge to touch it. She watched her children’s growing fascination. At last she turned to her husband, “But why would you bring it here? This is a Jain household! Anything could be inside.”

Suresh ignored his wife. “Bhautik, read us what the label says,” he instructed his son.

Bhautik’s voice assumed the air of one of the local politicians who combed the lanes and alleys of their district atop rickshaws during election time, delivering their speeches through hand-held megaphones, “Kraft! Processed! Cheddar! Cheese!”

Bhautik waited for his father to respond. Suresh, his brows drawn together, stared at his son. Then he said, “Now tell us what each of these words mean.”

Bhautik fixed his gaze on the red letters. He repeated the words to himself. Kraft. Processed. Cheddar. Cheese. Cheese, Cheddar, Processed, Kraft. Bhautik raised his eyes to meet his father’s.

“It’s soap, Bapuji,” Bhautik said. Then he smiled. It was possible, after all, that he was right. He turned to Aradhana, “Get me the tin-cutter and a knife from the kitchen.”

Aradhana obeyed. Ananti’s eyes left the tin and examined her son, suspecting that he was as clueless as they.

“I say we take it downstairs and throw out its contents, whatever it is,” Ananti announced.

Suresh looked at his wife and said, “Then why bother emptying it first? We might as well throw it away now.”

Ananti looked at the tin and fell silent. She felt her husband’s eyes on her.

Bhautik had cut an arc along the plate sheathing and was folding back a tin half-moon with the help of the knife to reveal a firm, ivory substance below. Bhautik and Aradhana struggled for nose space to sniff – while careful not to touch – the delicate fragrance of daffodils and lily of the valley that they had read about in their textbooks. They each took a deep breath.

“Chiii!” The siblings exclaimed in unison, recoiling from the tin.

“If this is their soap, no wonder they conquered all of India – this smell would make a Gurkha surrender without a fight!” Aradhana yelled through her pinched nose.

“It smells like damp sandals,” Bhautik added.

Silence returned. Bhautik opened more of the cover.

“I don’t think it’s soap, son,” Suresh concluded.

Bhautik probed the surface with the tip of the knife. “It’s soft,” he said.

“Maybe it’s chalk.” Suresh suggested. “The man told me he was a writer.”

“But it’s not powdery,” Aradhana observed.

Suddenly, Ananti slapped her palm on her forehead. “But what if it’s food! Non veg! You know those angrez will eat anything, even something that comes in a sealed box! I knew we shouldn’t have brought it into our house. I told you so.”

Bhautik poked the tip of the knife into the substance and ran it around in a small circle. He removed the conical piece onto the blade of his knife.

“Don’t you dare put it in your mouth, Bhautik!”

“I think you’re right, Mamma. It’s food.” He paused and looked at his mother. “We should taste it to see what it is.”

Ananti shrieked. Aradhana, too, cursed her brother and refused to eat one morsel of it herself.

Finally, Suresh spoke: “I will not taste it, but you have my permission to do so if you wish.”

“And who are you to give such permissions?” Ananti yelled. “We don’t know what this is! It could kill him! Are you giving permission to an Englishman to kill your son?”

The cone on the blade resembled a sweet, creamy barfi, but the smell still deterred Bhautik. He figured that whatever it was, the chance that he was sinning was big. Then a rhyme he had learned by heart for his English lesson entered his head:

Little Jack Horner sat in the corner,

Eating a Christmas pie:

He put in his thumb, and pulled out a plum,

And said, “What a good boy am I!

“I’m going to taste it, Mamma.” Bhautik raised the blade to his lips.

Before they could say anything, Ananti, Suresh and Aradhana saw the pasty lump disappear into his mouth.

“He’s choking! He’s choking! Get him water!” Ananti lunged towards her gagging son.

Bhautik spat the mush into his hand. He heaved and coughed while Ananti slapped his back over and over. She continued to slap him on the shoulder even when he had quietened down and stopped only to let him drink. Three pairs of eyes settled on the fourth, which were finally raised to meet them.

“It’s the most vile thing I have ever tasted,” Bhautik declared. He cleaned his mouth with tooth powder twice – and still he seemed to taste the foul, grainy paste between his teeth. He leaned over the small sink on the balcony that Suresh had installed after his first raise, furiously rubbing his forefinger over the ridges between his teeth until his finger burned.

Ananti had retreated to the jute mattress when it occurred to her that Bhautik would have to undergo another, different cleaning ritual. She had touched her son while menstruating. In Ananti’s childhood, purifying him of the effect of her touch would have required a thorough bath and washing of the clothes since he had been wearing cotton, not nylon or silk, which did not carry the same contaminating effect.

Ananti got up from the mattress. “Take a bowl of water from the kitchen and sprinkle it over your brother,” she said to Aradhana, who looked at her mother, expecting more instructions to follow.

“That’s it?” she asked as her eyes sought out her father’s for confirmation.

Suresh did not look up from his newspaper.

“For once, can you just do as I ask?” Her voice sounded tired.

Aradhana did as she was told, and then watched Bhautik clean his teeth for a third time. She hovered around the sink to see if her brother needed anything. His courage had impressed her. She would tell Rosie and Mary about it at school.

Suresh turned the last page of the paper and folded it into the gap between the bed and the wall. He stretched his upper body and yawned loudly. Then he picked up the open tin that was still lying on the floor where the family had sat around it.

“Don’t throw it,” Ananti said quietly so her children wouldn’t hear, expecting them to mock her for discouraging Bhautik to taste its contents while wanting to keep the tin. But Suresh did not hear her; Ananti watched him scoop his slippers up with his feet on his way to the door without interrupting his stride. She listened to his footsteps as he climbed down the stairs of their building. They grew fainter and disappeared. Ananti guessed that he was heading to the garbage heap at the end of the lane.

Aradhana entered and took out Suresh’s tiffin box from his satchel. Ananti heard her unclip and rinse it out in the kitchen with the dregs of water in the bucket. Tomorrow the buckets would be refilled and, as today, they would barely last until the night.

Soon Suresh returned. He walked up to the edge of the jute mattress and placed the empty shell at Ananti’s feet without a word. The jagged edges of the lid had been neatly bent flush with the inner wall of the tin. Ananti watched her husband climb back onto the bed to clip his toenails. She got up and stepped out onto the balcony, at this hour illuminated only by the room in her back. With her hands she moved the mounds of ash into the gleaming, empty tin.

Related posts from Verve:

Verve Trending

Sorry. No data so far.

us on Facebook to stay updated with the latest trends