One By Two

From the moment that Avni had shouted at her grandmother and then burst into tears, she had officially turned into a bridezilla. It was over the 20 gold-yarn batuwas that Nani was to crochet for the bridesmaids’ outfits. At the rate that she was going, they were not going to be ready by the day of the full dress rehearsal, four days from now and ten days before the shaadi.

Avni had yelled, wailed, actually: “At least from you I didn’t expect this tailor-master behaviour, Nanimi; and remember it was you who wanted to make them and not have us buy them.” And the tear storm after that outburst was not because of Nanimi looking stricken and trying to say “But…but definitely in time for the big day”; it was because ‘how can even family conspire to give me so much stress?’

There are crocodile tears and there are bridezilla tears. The former are fake and slappable, the latter are real, but slapworthy too. Slappable and slapworthy were her friend Trishala’s favourite words. Much human behaviour was categorised by her as slappable – for smaller misdeeds; and slapworthy – for larger misdemeanours. She would have definitely labelled yelling at grandmom as slapworthy. Bridezilla tears are sweetly explained away by near and dear ones as bridal ‘nerves’ and ‘jitters’, but quite a few people around do feel a one-tight-slap tingling in their palms when they encounter the bridezilla in full cry.

She hadn’t started out that way, Avni. She was not usually the princess of her own fairytale. She had earned her degree with a scholarship, the old-fashioned way, and not via the all-expenses parent-paid stint at a random US university that the NIPs – New Indian Princesses – around her were traipsing off to. Avni and Trishala were très disparaging when an NIP returned with a dubious degree, a prize catch husband, and had a many-day multi-location wedding for which papa paid up. She didn’t like girls who bled their daddies and she didn’t like daddies who leveraged weddings to overwhelm and outdo everyone around them. But things had kind of spun out of control with her own wedding and she hadn’t been quite able to recognise it and there was no one to say ‘Mad-or-what?’ with Trishala away till just four days before the wedding day itself.

It had started, the ballooning out of her wedding into something way larger than planned, not suddenly, but in that delicate way in which dissatisfaction begins? It’s something like when you move house; all your stuff is finally packed into the tempo-van. And then, what you thought was plenty of lovingly acquired furniture and other quirky and wonderfully precious possessions now look like a clump of derelicts huddled shabbily in the corner of the cavernous interior of the vehicle. And the thoughts begin to half-form: I have so little, I need more; my stuff looks so…pathetic…how could I have thought this is enough?

It was the wedding venue that first came under the scanner. Mohini Aunty said it would not look good in the wedding CD, because however much it was decorated it was finally just a ‘hall’. At first Avni and her parents laughed her off privately, since much of Mohini Aunty’s son’s wedding had been presided over mainly by a video company (a team with an actual director-of-photography in charge, who made them do retakes even of the pheras). But yes, the suburban hall did seem a bit ‘saddy-waddy, no?’ her mother had then wondered aloud. And the fact that it had been available so easily meant it was definitely not tony; it could not even be called a ‘venue’ actually; it was just a jazzed-up badminton hall, truth be told. There were still eight weeks for the wedding and the cards had not gone out, so a venue change was okay.

From there on, it had been a slippery slope. A larger and more upscale place with its own lawn and patio was booked (first they were waitlisted and then there was a lucky cancellation). But now it looked like their guests would not fill this place up enough, and why risk being labelled ‘poorly-attended’…so the guest list was fattened slightly. Then it seemed like the flowers that they had ordered would probably get lost in the large space…so why not opt for some of the extras, like that mogra-net canopy under which the ceremony could be performed?

And now, in this setting, Joshi-guruji, the old priest who had officiated for births and deaths for years, would seem a trifle tacky, sweetheart though he was. His tatty brown socks which refused to stay up on his skinny calves but which he wore throughout any ceremony because they covered the corns and bunions on his feet, now seemed a tad embarrassing. His eagerness to translate the Sanskrit shlokas into English for the benefit of ‘esteemed foreign guests’ now appeared a bit of a hazard, given his thick accent. An upgrade would have to be arranged. Photogenic priests with a touch of urbanity were not easy to book. They were on high rotation during the wedding season and came in pairs. They had to be chased, enticed and secured with an advance deposit. And a back-up would have to be kept ready. They also cost heftily more than Joshiji and a car would have to be detailed just for them.

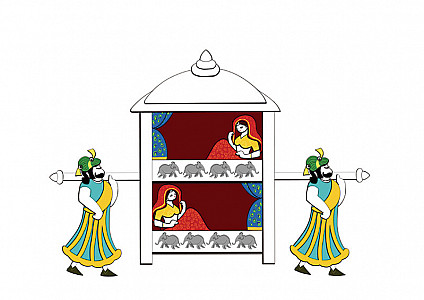

The video people wanted to know what the theme was – colour and content? She was shown options briskly on an iPad by the video man’s second assistant. Avni chose ‘Indian miniature paintings’ as her theme. There had to be colour co-ordinated bridesmaids’ outfits and there would be a need for male counterparts dressed to look the part. There was a strong suggestion that a few striking looking young men and women be hired and mixed in with the real friends; plus a few young white people always added that global patina. Only two of Avni’s white friends from the USA were attending…but, of course, more could be arranged, the video girl assured her – sometimes almost for free, if you planned in advance and got a bunch of budget tourists to do it.

So the western-style nosegays and wreaths and bouquets that the venue chap was throwing in as part of the package, would not do at all. It would need to be a thick green foliage-type background, just like in Indian miniature paintings – mango branches, preferably with fruit hanging on them, banana plants, flowering parijatakas and basins of lotuses and water lilies.

When the backdrop people (brought in by the video people) said that peacocks could be arranged, real live ones, and a pair of very realistic fibre-glass deer, that’s when Avni’s parents said no and Avni said why not? She had not yet shouted, but here she placed a firm foot towards bridezilladom. “Why not?” she had asked sulkily about the peacocks. “It’s not like we’re ordering elephants.” And her parents had hastily said okay to the peacocks (so that the word elephant did not remain in the air, in the realm of possibility, for too long). The peacocks are kept on an invisible nylon string, they were assured, so that they stand around but don’t flap about or take to the air or go for anyone’s food or anything. No guarantee that they would fan out their tails, though. And, they needed a supply of green dhania, so that they didn’t peck at the foliage and dhania had soared to Rs 40 a bunch currently, so that would cost a little extra.

“Bring on the dhania,” her dad had intoned loudly and then in an aside to her mom had added, “As long as these peacocks don’t need to eat crushed gemstones, in keeping with myth and legend.” He had been shushed.

Now not just planners but art-researchers had got involved. A story-board was made, where every ceremony (which had grown from three to seven) was painted on a large piece of ply, with the placing of people, priests, peacocks and other paraphernalia pinpointed precisely.

About 20 days before the wedding, Bipin the groom’s bewildered reaction to the new spin on their wedding plans was causing its own aggravation. Avni listened tensely as he told her over the phone how he had ‘sat on’ all the women in his family, to have them accept that the wedding was going to be simple and a one-day thing. Now he felt foolish, with the whole thing growing so many bells and whistles, effing hell, he said. “Stop swearing and this isn’t about you,” Avni said coolly.

“Not about me? This wedding is not about me? I see. Do you even hear what you’re saying Avni?” he had asked even more icily.

“Well you know what I mean,” she had said.

And he had replied: “I don’t believe I do.”

“Bipin is being very polite, precise and pissy,” she emailed Trisha.

Tensions mounted, as the caterers, the make-up woman and the live music people were reviewed, rejected, recalled or ranted about.

Trishala arrived from New York four days before the wedding day. Avni and Trisha were known in their college years as the ‘one-by-two girls’. Both small eaters, they ordered just about everything in the college canteen or in the Udipi restaurant across the road, or even in fancy restaurants when they were older, in a one-by-two arrangement – one portion, and an extra plate for the other person, so that they could go halvsies. “Ek chai, please, one-by-two; ek sweet corn chicken soup please, one-by-two; ek masala dosa please, one-by-two” some of the boys would chorus whenever the two entered the canteen.

The evening of the day that Trisha landed, they caught up over a plate of hakka noodles and momos (divided one-by-two) at their favourite place. When she had heard it all, Trisha darkly declared much of Avni’s expanded wedding plans and behaviour slappable and slapworthy. And she hadn’t yet heard about the shouting-at-Nanimi part.

“Where were you when I was letting this whole thing run away with itself?” Avni wailed. “I now have a big fat flabby wedding.”

But, Trisha, ever the efficient thinker, now cautioned her, “It will be even more bratbridezillaish to indulge in pangs of conscience, suddenly scale down this wedding and have your dad lose deposits and advances, ya? So now let’s think this through…which of all this dumb stuff you can reduce easily.”

Just before they went to bed, deciding that at this stage it would be best to leave all the wedding arrangements as they were, Trisha said quietly, “My big news is that Raghav and I got married in New York three days ago. It was just the two of us and five friends. We will tell our parents, but only 60 days from now, when all the paperwork is sewn up.”

Trisha’s Raghav came from a political family who would have most definitely not approved of her. Dark, diminutive, and with the disposition of a firecracker, she was the adopted daughter of left-leaning academics. Her lithe athletic little body (she was a sprinter and gymnast for her university), she and her parents sometimes jokingly, and without any self-consciousness, attributed to the possibility that she was the child of a Mumbai’s dombari, the street acrobat. Not quite the lineage Raghav’s family would like to acknowledge or associate with.

Avni let out a yelp of shocked delight: “But your parents? They like Raghav. Tell them about it, Trish, at my wedding.”

“Ya, but they do think his family is high-flyin’ trash…and can you imagine anyone coming to any kind of agreement about what kind of wedding it should be? His lot would have insisted on a wedding that involved helicopters, security, and the cordoning off of roads in their home town and in the city. My parents would possibly have opted to not attend or attend in a state of deep embarrassment!”

Avni completed the thought for her: “And you would have liked something in between, but no one would have let you, and so this New York magistrate thing…”

Trisha’s usually cool brown eyes were moist, and she said softly, almost shy, “And we’re expecting a baby.” Then she added hastily: “I’m just a few weeks pregnant, so I will fit into your bridesmaid outfit.”

Avni’s squeal brought both her parents out of their bedroom and they went back only when they got both girls to get into bed and turn off the light. Life was revealing itself in the most compelling and unpredictable of ways. Trisha fell asleep and Avni fell into that half-awake half-hallucinating state from which emerges the most inspired of ideas.

The one rearrangement that Avni insisted on, the next day, was the reinstating of the priest Joshiji and never mind that the designer duo of priests would not return the hefty advance.

The venue was truly straight out of an Indian miniature painting. A raised platform with a golden railing around it, dense foliage as the backdrop and those promised peacocks strutting beautiful, nonchalant. Trisha took her spot behind Avni as bridesmaid. Her Raghav was amongst the people behind Bipin.

Only those who listened carefully may have noticed, the mantras had two unusual words in them. Besides the names of the bride and groom, were the names Raghav and Trishala, woven and blended carefully in. As Avni and Bipin took their saat phere around the fire and the guests surged around them, Trisha and Raghav slipped away to step along an outer circle, one that Joshiji had earlier marked with auspicious symbols.

As the mahurat, the moment, arrived, they returned to their places. Joshiji joyously chanted the last phrase – Shubha Mangala Savadhan! Rice grains and blessings rained down from the guests, plenty to go around.

“From bridezilla to wondergirl,” the groom murmured, as they stepped off the dais, man and wife.

“It’s called atonement…and am I glad I got a chance to do it this way,” Avni said into his shoulder.

“Ek shaadi please, one-by-two!” Avni’s father whispered, as he hugged all four newlyweds.

Related posts from Verve:

Verve Trending

Sorry. No data so far.

us on Facebook to stay updated with the latest trends