Ode to Mortality

I have always felt far removed from the English Romantic poets. It isn’t that I question the genius of a Keats or a Coleridge but merely that what they had to say doesn’t echo within me as perhaps the verse of a more contemporary poet does. Even my admiration for Lord Byron is founded on his persona rather than his poetry. And thus this essay would have remained unwritten but for serendipity.

Easter Monday, Rome was filled with what seemed to be all of Italy. It was as if towns and villages all over the country had emptied out; fires stamped out, doors locked, fish fed, dogs put on their leashes and everyone – man, woman, child, dog; grey old plodders, gay young friskers; mothers, fathers, uncles, brothers; had all trundled and truckled into Rome. Add to it the Japanese, the Americans, the devout pilgrims and nuns/frocked fathers of various orders and us. And everyone seemed to be everywhere.

‘Rome is yet the capital of the world. It is a city of palaces and temples, more glorious than those which any other city contains, and of ruins more glorious than they’ Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote to Thomas Love Peacock. An awe that the crowds thronging Rome seemed to share for they flocked to every point that was marked with a red circle on the tourist map. From the Dunkin Donuts outlet to McDonald’s to the Trevi Fountain, the Vatican City, the Forum, the Colosseum, museums and galleries, on the roads, in the cafes, rather like Hamlyn’s rats, the tourist spared nothing. At the best of times I hate crowds and Easter time in Rome was beginning to seem like a mistake and an expensive one at that.

In sheer desperation, we sought places everyone else dis–dained. And so it was as we stood near the Spanish Steps, where it seemed the whole world had also gathered, wondering if we should brave the steps – climbing up the steps was easy compared to wedging our way through the crowds – that we spotted a little sign alongside the steps that said Keats-Shelley Memorial House.

The guidebook made a mention of the house but I wasn’t sure if it was open to the public and besides it seemed rather morbid to want to visit a house where a man had died. But then without looking for it, there we were. Besides, everyone seemed to ignore the house and preferred to sit on the steps, licking at their ice cream cones (which is perhaps Italy’s best kept secret: the cornucopia of ice creams and outlets), kissing or putting new film into their cameras, yelping into their mobiles and sometimes trying to do all four things together.

Despite no one wanting to climb the many flights of stairs to Keats’ apartment, the house is part of Roman folklore. For generations, the Piazza di Spagna has been visited by architects, painters, musicians and poets who all lodged here. Tobias Smollett, George Eliot, Goethe, Coleridge, Shelley, Byron, the Brownings, Henry James, Edith Wharton, Oscar Wilde and Joyce were just a few of the many who were attracted and inspired by the celebrated centro storico.

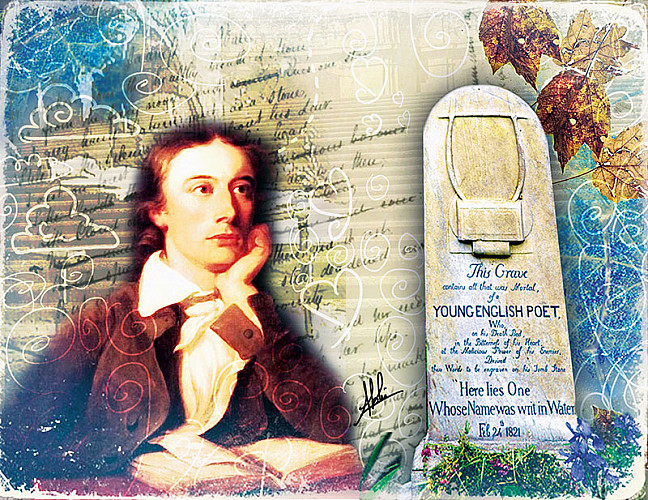

But it was Keats who became part of the tourist folklore by dying there. And dying young. John Keats was born October 31, 1795. He attended school at Enfield, where he made friends with the schoolmaster’s son, Charles Cowden Clarke. It was Clarke who first introduced Keats to literature and encouraged him to write poetry. It was he who, one night, showed him Chapman’s translation of Homer’s The Iliad and Odyssey and it was on his breakfast plate that Keats, the next day, left the famous sonnet On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer. Keats studied to be an apothecary and spent six months at Guy’s Hospital in London training as a surgeon. However, in 1816, encouraged by his friends, he decided to give up medicine to devote himself entirely to poetry. His first volume of poetry was published in March 1817. At the same time he began to suffer from persistent sore throats. As he became increasingly ill, his doctors and friends told him he would not survive the rigours of an English winter. It was believed that the Italian climate could save him and that the change would do his spirits good too. In the end it was the thought of Fanny, the girl he was in love with, that made him decide. It would be better for her if he went; she must be spared the experience of his death.

His friends decided that he should go to Rome where there was a well-known Scottish doctor, James Clark, to look after him and where the climate was considered suitable for the treatment of the disease. Keats did not write a single line of poetry during his time in Rome. Only once did he succeed in putting pen to paper; it was on November 30 when he wrote to his friend Charles Brown where he concludes ‘I can scarcely bid you goodbye even in a letter. I always made an awkward bow’. Keats expressed the wish that on his gravestone no name or date should be written, only the inscription ‘Here lies one whose name was writ in water’. Above it was to be carved a Greek lyre with four of its eight strings broken ‘to show his Classical Genius cut off by death before its maturity’ as Severn later interpreted it.

He was 25 years old when he died. The exterior of the house is exactly as it was when John Keats travelled to Rome and as I walked through the rooms of the apartment pausing to feel the atmosphere of sadness that mounts every wall and flake there, I could for the first time understand the poignancy of Keats wanting to capture timelessness as hewn on the sides of a Grecian urn. Of wanting to cherish eternity when he perhaps knew that even the average span of mortality was going to be denied to him.

Related posts from Verve:

Verve Trending

Sorry. No data so far.

us on Facebook to stay updated with the latest trends