Sophie and the Black Box

I can hear the sound of the doorbell clang through the apartment inside. It seems to bounce against the walls, only to be thrown back at my face. I give it a few minutes, and when there is no response, I ring the chimes again, this time impatiently. A few more minutes pass. Then, just as I am about to knock on the door, it is flung open.

I look into a pair of blue-brown eyes, positioned a foot above me, and set in a face, which is nut-brown and filled with a rough, light brown beard at the edges.

“What?” The man barks.

“K… Krish… Krishna?” My voice emerges all shaky and I clear my throat trying again. “I am here to see Krishna.”

***

Whenever I asked my grandmother why she was dark-skinned, she would say it was because of the hours spent running wild through the moors when she was growing up. It wasn’t until I inherited her little black box — upon her death — that I discovered there was a little more to it than that. Here, I have to confess that I was more than a little surprised to find she had left me something in her will.

Perhaps it was because I was the darkest skinned in my family…and resembled her the most.

Or because I had been named after her.

Either way I should have felt some affinity with Sophie. But I didn’t. She and I did not have much to say to each other during the time she lived.

She didn’t say much to anyone, actually, least of all to us, her grandkids.

She existed in a parallel world, a reality far removed from my everyday life. She refused to be admitted to a care-home, instead spending her last decade on her own, in her little cottage on Dartmouth moors. The same house where she had been born almost 80 years ago.

I marvelled that it was possible for someone so old to live this long. Was it even possible for her skin to hold the sea of wrinkles, which marred the placid surface of her forehead?

Looking at her was like peering into a long black tunnel, one that had no beginning. In comparison, I felt like a little spark of light — my life as short as the length of a matchstick.

Yet looking at the black box, which she had bequeathed to me, distant echoes from my childhood trickled down my spine. Scenes from a long time ago; when she had smiled at me, told me bed-time stories of what it had been to grow up in the city of her birth…a place too far away for me to comprehend. A city I had never been to. A country, which felt too alien, too exotic for me to be a part of any way. Those memories had been wiped away in the haze of the electronica of my youth. Clubbing, boys and the allure of social media had long ago deleted the leftovers of any recollections.

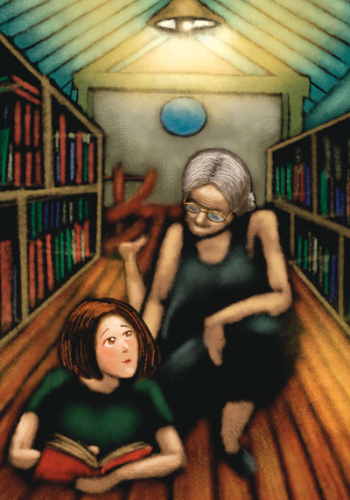

My last memory was our family at the obligatory Christmas lunch, at her place. In my introverted teenage years I much preferred having Christmas lunch with Nana Sophie. I remember one particular Christmas — when I had just turned 13 — I sneaked away to the cold draughty attic, and had picked up a book to read. A murder mystery written by Agatha Christie as it had turned out to be. Soon I was engrossed in the adventures of Miss Marple. Somehow it seemed apt that I should be reading about an energetic granny traipsing around the countryside, trying to solve murder cases, in my Nana’s home. Nana had been agile enough then to walk up the stairs, and come in search of me. “Have you read all these books, Nana?” I remember asking her.

To which, she had smiled, and, walking to the bookcase, had run her fingers lovingly over the spines of the, dust-covered jackets of some of them.

“Yes, of course.” She said to me over her shoulder. Picking out a book she flipped it open to a page and walked over to me. “This…this one is my favourite Sophie.” She handed it over to me, and ruffling my hair gently, walked away. It was a compilation of comic books. The chronicles of the Legion of Superheroes — a fictional team of superhero characters set in the 30th and 31st centuries.

No, I didn’t know Nana too well. Which I why, I cannot explain why I burst into tears at her wake.

Perhaps, it was the sight of seeing someone dead in an open casket. Well, to be fair it was the first time I was seeing anyone dead. Or perhaps it was just that she was wrapped in her blood red, bridal sari. Rather incongruous on a freezing Tuesday afternoon with the rays of the setting sun pouring in through the stained glass window of the primarily middle-class, white neighbourhood area of Tavistock on the edge of Dartmoor National Park. Seeing her in those bright colours — a contrast to the greys and brown standard dresses, which is what she had normally worn — was like a piece of puzzle falling into place. She had never belonged here, had she? Somehow in death she had managed to do what she couldn’t in all those years she had been alive. Send out the message clearly, that she had fought against her identity, fought to not belong to where she came from.

Now, here I am sitting in her little cottage; the one she has left to me along with this black box. Somehow I am sure she has something to hide. Perhaps I have known it all along. She had never so much as hinted so; as content as she had been to live within the bubble she had created for herself. And yet, she had been so transparent. Trapped below the surface, the rainbow colours had meshed into a tempest. One, which I am about to unlock.

Having coerced the parents into letting me stay a night on my own in her cottage, while I can still feel her presence in the room, I reach for the box cradled on my lap. My toes dig into the carpet, as if holding onto the earth for support, and I turn the tiny key in the lock, flipping open the lid of the box.

And I am almost disappointed by the anti-climax. Nothing shatters. A pile of letters gaze back at me, paper frayed with age, the handwriting is a firm slash across it. Even without reading who they are from, I know they are love letters.

***

It’s 38 degrees. I know because the temperature on my iPhone screen says so. It seems I am going to be spending my gap year in India. In Bombay, to be precise.

All I have to go on is that the person sending the letter is a Krishna. I had known Nana Sophie grew up in Bombay, but she had left the city when she was 13, moving with her parents to Dartmoor. She had met and married my grandfather at 18 and had proceeded to have a series of miscarriages before finally giving birth to my father at 26. Grandpa had died shortly afterwards leaving a young widowed Sophie to bring up her son. It seems on the only trip she made back to Bombay in her later 40s — around which time my father would have just already been married — she met her childhood friend, with whom she re-established a friendship. She had proceeded to come every year over the next ten years and then had abruptly broken it off. Refusing to write to him. And yet the letters were there. They kept coming, pleading with her to write back, worried about her, the helplessness from the letters pouring out of the pages, the barely contained passion leaping out at me, surrounding me, forcing me to open the window of that overheated little living room of the cottage and taking deep breaths to clear my head.

I didn’t sleep that night.

The next morning my mind was made up. I was going to Bombay. To find my roots, so to speak. Or at the very least to track down the only living embodiment of what had been a very important part of Nana’s life. Enough for her to keep it a secret from all of us. The very fact that she did not mention the letters to any of us before she died intrigued me. And yet, in death, had left me with enough clues to follow the trail. It was reason enough to find out what had been eating away at her in her final years.

Besides I did need a destination for my gap year. She had left me a small cash inheritance too; enough for me to book my tickets to Bombay would blinking an eyelid.

Now, seated in what passed for air-conditioning within the confines of the cab I had hired at the airport, I look out of the window…. At the four-lane-wide traffic of cars and beyond that, to the blue-green of the Arabian Sea. The wall, separating the traffic from the waves, seems fragile. Like it’s too weak to hold back the whites of the choppy sea, which even as I watch splash over the side onto the pavement. It drenches the couples that sit with their back to the world. They seem lost in each other, oblivious to the sun, the heat and the water anointing them with sweat and tears.

All I have to go on is an address, and I can’t wait. I take the cab straight to Krishna’s flat. The phone number scrawled below the address has not responded despite my having called it a few times. But, then, I haven’t come to India, only to meet Krishna after all. I can do what any respectable person on a gap year would. Go clubbing, meet the locals, have a one-night stand. As my mind wanders over the possibilities, the car turns off onto a side road, and suddenly we have left the traffic behind to enter a different dimension.

Here, it’s quieter, the trees overhead providing an umbrella from the elements. The car drives smoothly now, and it is almost as if a carpet of leaves has covered the vehicle, muffling the street sounds. We draw up outside a tall building. Coming to a stop the driver turns around indicating I should pay him the amount showing on the meter reading. It’s a big number, with many zeroes. Certainly more than what I have paid for any taxi ride in London. Yet, my hasty calculations indicate it’s just short of £20. All too soon, I am standing in front of the door on the 11th floor of the building, pressing the door bell, which rings through the interiors.

***

“Krishna?” The man looks at me, brow furrowed.

I nod, and fishing around in my bag, remove one of the letters I have bought with me to give to the guy. As he reads it I try to see past him into the darkened interiors of the house. A sudden tiredness overwhelms me and I sway slightly, dropping the bottle of water clutched in my hand. I bend down to pick it up and straighten to see, that his face has gone carefully blank. He steps aside and indicates I should follow him.

I walk behind him, dragging my suitcase.

“Leave it here,” he points to a space next to the overstuffed sofa in the living room. Thankful to be rid of my load I deposit both, my wheelie and my backpack, before following him through a corridor. I peer into the kitchen and the three bedrooms we pass, before reaching a room at the end of the passage. He knocks, and listens at the door before opening it and indicating I should go in. I walk in to see someone standing at the window. I blink at the silhouette, which turns to me.

“Krishna?”

She nods, looking at me. Her face is expressionless, grey and pockmarked. Just like Nana’s beloved moors.

London-based Laxmi Hariharan is a global marketer and content branding expert with over 20 years of experience in the global media industry. Her debut work, The Destiny of Shaitan, won gold at the global eLit awards. She has subsequently penned her second work, The Many Lives of Ruby Iyer.

Related posts from Verve:

Verve Trending

Sorry. No data so far.

us on Facebook to stay updated with the latest trends