Geeta Rao on The Ministry of Fashion

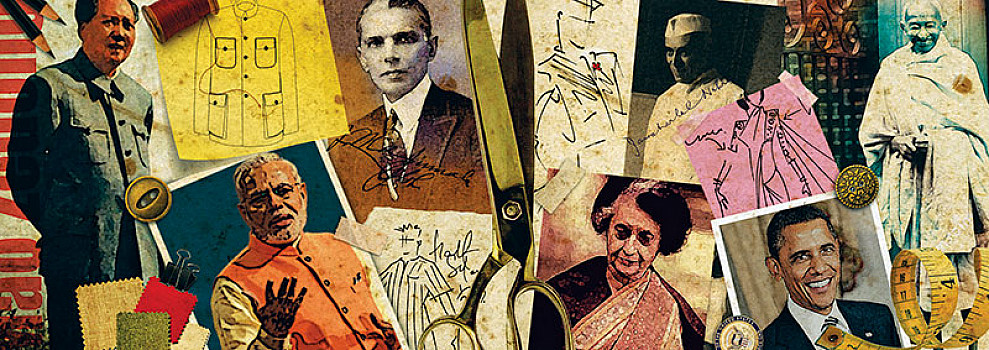

Being elected to office is simply not enough — the choice between mull and Malkha, Bandhej or Bhagalpur and being able to have an outfit named after you, may decide your political future from now on. Blame it on the Mahatma. He invoked the khadi clause and cast in stone an unspoken sartorial code for politicians.

The swadeshi movement was a political one, but khadi became its symbol, a powerful fashion tool and a revolutionary statement as hordes of people dreaming of freedom switched to homespun cotton. In a counterpoint, continents away, France was celebrating the creation of artificial silk or rayon, while New York was celebrating the Jazz Age and the flapper dress.

The sustainability and the ethical fashion movements came much later to the West, but the Mahatma had thought about handlooms and khadi in such meticulous detail that few could challenge him. Such was Gandhi’s dress manifesto that it never disappeared from our sartorial consciousness, especially if you chose politics as your profession.

Politics and fashion have been strange bedfellows, willy-nilly making great leaders into fashion icons. Nehru took the Indian achkan global and with a few stylistic variations left his name on it for all time as the Nehru Jacket. It works at black-tie events, and the Beatles made it cool. And the Nehru Jacket is enjoying a great revival at the moment among a younger generation of natty dressers and not only netas.

Likewise, Chairman Mao left his indelible stamp on the Mao Suit as the Communist party uniform.

Jinnah was rumoured to have owned 200 bespoke suits and known for his suave Westernised style. (He has an unexpected modern-day counterpart in Argentina’s Cristina Kirchner who is rumoured to own over 200 black dresses.) An interesting article on Jinnah in Pakistan’s The Express Tribune tells us that Jinnah also gave Pakistan its national dress: the salwar, the sherwani and the Kashmiri fur cap, karakul. Also known as the Jinnah Cap, it was co-opted because the fez was seen as old-fashioned. The Quaid-e-Azam did not set out to be a fashion guru but the quest for national identity made him one.

Indira Gandhi could have virtually run a ‘States of India’ campaign with her flawlessly selected saris which featured the best of Indian handlooms — silks (for international trips and conferences), and the most beautiful of cottons and natural weaves for her India rallies.

Sonia Gandhi wears her stunning collection inherited from mom-in-law with crisp confidence. It is her collection of handlooms with provenance that have made her feature on ‘Best-Dressed Political Leaders’ lists that global magazines love to come out with.

Both the Gandhis showed great political finesse in their choice of looms. There are enough images available to see an enviable collection — Narayanpet, Pochampally, Sambhalpur and Bengal handloom, and khadi, each chosen for an appearance not only in the state, but in the district of the weave.

There are some leaders who could have made the cut but ended up making the wrong sartorial choices. Jayalalithaa has a formidable collection of Kanjeevarams and South Indian silks but chose to cover them with matching capes. It could have triggered a fashion frenzy. After all, when was the last time someone innovated with the sari but it fell on its face and never caught on?

Then, as we were chugging along in this fashion landscape, along came Mr Modi to shake things up, sartorially speaking. Turning the narrative towards his crisp, starched and dapper appearance, coloured safas, colour-coordinated jackets and even a monogrammed suit quite unheard of on the Indian landscape. The only one ironically to appear as starched and crisp as him is his political rival Sonia Gandhi whose pleats are never out of place (In all fairness, Mr Chidambaram’s dhotis and angavastrams are also ‘Surf ki dhulai mein samajhdari’ white and crisp.) Mr Modi is rumoured to change his clothes three to five times a day to retain his starched level of crispness.

Mr M has global partners in his well-dressed quest. From Internet gossip we know that Helle Thorning Schmidt, the Danish Prime Minister, changes her clothes four times a day and has been called a ‘Gucci Diva’ for her love of designer clothes.

Joyce Banda of Malawi is fabulously turned out, wearing her national dress with pride and dazzling colourful combinations, and has a vast collection of hats. Mr M can match her hat for hat with his Rajasthani safas and pagris. If Obama has the Obama Suit (two button, single-breasted) tailored by Hartmarx of Chicago, Mr Modi has the Modi Kurta and JadeBlue in Ahmedabad.

The Modi Kurta, now famous, has a court case and settlement story behind its patent already. JadeBlue has emerged the winner, the appointed purveyor of the said Modi Kurta. While you could buy a version of this shorter kurta with short sleeves at the Khadi Gram Udyog outlets, the anatomy of the Modi Kurta is crisp khadi in linen colours with a hint of pragmatism — short sleeves and fitted. If the sleeves are long the kurta has cuffs and buttons like on shirt sleeves making it look more formal. The Modi Kurta, priced at approximately 1,500 rupees, is available in rose pink, self-textured or blue-and-black chequered, next to the Dulha and Bespoke suit categories on the JadeBlue website. Like Madhuri Dixit’s sari from Hum Aapke Hain Koun…!, it is a bestseller.

On a recent visit to India, Michelle Obama’s carefully selected Bhibu Mahapatra outfits paled into insignificance in the face of the great leader’s sartorial splendour. The Washington Post headline said, ‘Move over Michelle Obama. The new fashion icon is here.’

The monogrammed suit was a fashion faux pas but for the rest of it, Mr Modi has released the inner sartorial-ist in parliamentarians and we are going to see an increasing number of fashion statements from younger politicians. Expect fusion clothes, newer textiles, revivalist weaves and more vibrant colours in Parliament.

But he has also unleashed more scrutiny. Now a neta can expect the electorate to ask whether his or her clothes are made on a power loom or handloom, is pure or poly khadi, with Chinese or ahimsa silk, which state and district the cloth was woven. The public isn’t ready to see Italian linen in Parliament just yet.

In Indian political history, textiles have sent out an important social message — khadi for service to the poor, Indian handlooms and textiles for supporting the arts and crafts, and ahimsa silk for supporting non-violent cultivation of silkworms. The more obscure the weave, the more displaced the tribe who wove it, the more your dress code speaks of how much you care.

Never mind that the poor weaver, unable to afford the cloth he or she was weaving, has switched to polyester and nylon. Or is queuing up for NREGA, as weaving is simply not going to make him or her a living. Or that we may be shutting down handlooms forever.

Related posts from Verve:

Verve Trending

Sorry. No data so far.

us on Facebook to stay updated with the latest trends