Matters Of Style

The word for it was ‘stylish’. Stylish girls had Lady Diana haircuts, wore low-wedge heels and chocolate corduroy bell-bottoms. Some wore midis and some wore maxis and some wore minis. Ribbed skivvies in single colours were in. Flared, high-waisted jeans and Keds. Or tight churidars with lots of churis around the calf, matching kurtas in pink satin that reached just above the knees, and chunnis wound around the throat but not covering the breasts. Dark leather moccasins with coloured beadwork on the front. Chunky sweaters. Chiffon saris patterned with gardens.

The stylish were a tribe of their own — they either had cascades of hair, sometimes plaited, such as Nazia Hassan’s, or that layered, feathery bob copied from the Princess of Wales.

She had just got married and everyone seemed quite certain they knew her. She was stylish for sure. Ish, so stylish, girls said to each other. It meant you looked fine, or it meant you were attempting to look fine, and could thus be mocked.

We sisters were less than 10 years old and not yet stylish. Perhaps we’d never be. We could not aspire to stylishness, being skinny, awkward, myopic and un-wealthy. We didn’t have what it took. The right clothes were crucial to being stylish, but not just the right clothes either. A worrying mystery was part of it too — something ineffable about the way a sleeve caressed your wrist or a collar enclosed your throat, about how you walked, tossed your head, put your hands in your pockets. Leaning on the brick garden railing we looked out for the stylish every evening. Meanwhile I knitted panties for my dolls and let my hair grow till my waist while my sister’s was too long to be short, but too short to be long.

She could have entrusted herself to our left-hand neighbour, who’d trained with Shahnaz Husain and even looked a little like her — smooth and plump and confident. The lady had recently set up a beauty parlour in her front room where a poster of her big-haired, big-eyed heroine hung and on the shelves were jars of pink and black and green beauty products. We’d been in there to shyly confer with her. She could give Lady Diana haircuts for 50 rupees. Her husband was out in the compound of their bungalow where his long, big-snouted, copper-coloured antique car was parked, calling out for their Pomeranian. Pom-Pom! We heard him yelling this name so often that it was what we called him. Pom-Pom! But we didn’t have 50 rupees to spare for Shahnaz.

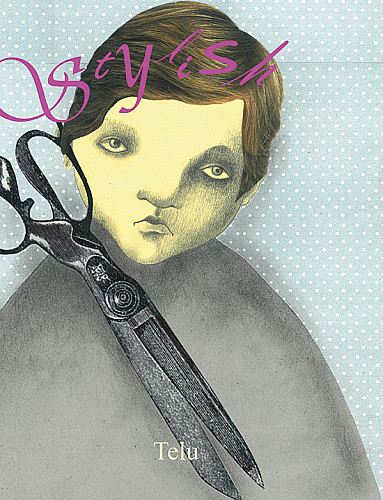

So one Sunday when I was nine and my sister was seven, I took our grandfather’s scissors, the heavy iron ones he used for his tailoring, and said to her, “Let me give you a haircut.” At this point in my life, I was forever running towards or away from something, every game involved flight or hiding under dusty beds, flinging the basketball far and away, climbing a ladder to the roof for the badminton shuttle. I would trip and fall, twist ankle or wrist, then be swathed for weeks in Relaxyl and stretch bandages. But I’d also pick myself up and carry on. I could not sustain the hoopla-hoop or turn perfect cartwheels like our right-hand neighbour but I taught her to skip. She and my sister were the same age and friends. I taught them skipping, single and double, how to twist the rope in mid-air. I was the head skipper. I could outrun everyone and deftly bring down oranges from our trees with the clefted bamboo stick, but I was accident-prone. I had a history of crashing into glass doors when I was younger. At two, I had managed to knock into a pot of bubbling porridge and burn the skin right off the back of one hand. At five, I dropped deep into a forest stream and almost drowned.

That winter morning, I snipped a little of my sister’s hair and it came away so easily between my fingers. I was restless, eager to bring some novelty into our lives. Even though we had Liril soap to bathe with and Cuticura talcum powder, a couple of nice dresses each, made by our grandfather, and new, very shiny sandals, none of this was stylish. In fact, the sandals were downright telu, which in the lexicon was the very opposite of stylish. They were too glitzy and so they were ‘telu’, which was a word we had made up to brand unstylishness, describe those who were pariahs in the house of style, who cared nothing for the oil dripping from their braids and the missing garters in their school socks. They were telu, others stylish, and we hung on desperately somewhere in between. We put on our shiny sandals reluctantly and perused old copies of Seventeen at the right-hand-side neighbour’s, brought in by her foreign relatives, agape at the denim dungarees and leather jackets, feeling ourselves aglow with the possibilities of stylishness.

We were sitting on the outside steps, my sister with a towel around her shoulders, compliant, trusting, me with those big scissors I could barely handle. I cut off her rat-tails and cleared her neck. I took up tufts and let them fall away. The hair on the back of her head started to thin out.

I combed and snipped, urging her to sit still. Then I aimed the scissors at her fringe.

Grandfather was not yet missing his scissors. He wasn’t tailoring this morning but he was often at it. For birthdays and festivals, he stitched clothes for us out of small squares of ordinary cloth and thin air. He would consider an expensive frock worn by the right-hand neighbour and turn out a perfect imitation in a couple of days, right down to the ruffled sleeves, smocked front and lacy frills. He stitched all the clothes he wore — the warm, buttoned, woollen vests and the sharp-edged trousers. He stitched quilt covers and shopping bags and kurta-pyjamas. It was him and his old, black, hand-cranked Pfaff, well-oiled and singing; the gold-edged pockmarked silver thimble that went onto his forefinger when he took up hemming and putting in the buttons; the faded British-era biscuit tin in which he kept his threads and bobbins.

Grandfather was an artist, but he was not stylish. He saw to it that we were clothed and to supplement what he made us, he’d go to the footbridge in the town’s market square where the sellers of second-hand clothes had their stalls and buy us trackpants and winter jackets. They had labels from abroad and looked crumpled. Rumour had it that they were meant for the poor in Bangladesh, not for the sellers on the footbridge and certainly not for us. I’d listen to George Harrison’s song for Bangladesh and feel guilty about those clothes.

Meanwhile, the thrill of taking matters into my own hands and the scissors I was now aiming at my sister’s fringe. The first attempt was hesitant and led to uneven results. I gave it another go and the lopsided look improved. Strands poked down from one side which I took away. I combed her hair sideways. “Show me,” I said and it looked alright. I had given her a haircut in the sense that I had cut her hair. But there was nothing stylish about it. Where were the perfectly-set waves that crowned the princess’s head? Where was the glamour of that golden crop? I pulled down the hair over her forehead and started snipping again.

Careful, said my mother, from somewhere inside the house, but she was distant. I imagined she trusted me because she let me make tea and handle knives, clean out the rice and broom the rooms. In any case, I couldn’t confide in her about our lack of stylishness because she was stylish herself, impossibly so. She wore silk saris in thick colours with matching lipstick, and had her hair done at Jennys, which was the oldest stylish place in town. She owned fascinating shoes — brown suede and blue leather and a pair of burgundy, crocodile skin, handcrafted high heels made to order by a Chinese shoemaker. She used only Yardley and Max Factor, and wore pure wool cardigans. So when she said — careful — both my sister and I knew it was to be taken only half-seriously. If I fell off the roof and broke my neck, if the open wound on my knee from falling on the tar and chip compound of the right-hand neighbour’s turned septic, if a Diwali cracker burst in my hand or if Pom-Pom escaped from the left-hand neighbour’s and bit me, she would rouse herself. For the rest of the time, she merely scolded absent-mindedly.

The hunt for ‘stylish’ continued despite my mother. My sister and I cut out pictures of luxurious clothes and lip-glossed women from the magazines and pasted them at odd angles into old notebooks. Grandfather made me a dress from a bedcover, patterned with blue clocks. For my sister he refitted an old dress I had grown out of. We got a TV and watched Shabana Azmi and Zeenat Aman who were stylish and the Doordarshan newscasters who were not.

My sister’s fringe was now shorter but uneven. I cut some more. Now it was straighter. I cut a tiny bit more. Now it was uneven again. And so on till more and more of her forehead was revealed and then the top of her scalp began to show. And still that line of hair wouldn’t fall straight. Suddenly she demanded to see a mirror. “What have you done?” she screamed. She looked like the victim of an illness that had selectively eaten up her hair. My mother came out and my sister finally began to cry.

Some moments of mixed emotions followed: my mother’s great exasperation at my stupidity even though she had originally acceded to my helpfulness towards my sister, my do-it-yourself zeal. My own conviction that I had missed stylishness by a whisper, that a few snips more or less would have done it. My sister’s sense of adventure dissolving into a feeling of betrayal. “Cover her head and take her to the barber,” said my mother. So the two of us went, ignominiously, down the street — me shamed and she with a knitted woollen cap concealing her disfigurement. There was the grocery shop where we bought our atta and soap, the typing school, the pakoriwallah who doubled as an electrician, the mithai shop, the paanwallah, the gentleman in a dark suit who sold toffees and hard-boiled sweets out of huge glass jars along with pencils and exercise books, and then the barber in his dirty white pyjamas. He was the one who usually dealt with our hair and he had no truck with style and Lady Diana. I had to explain the problem to him, while my sister sat on a wooden plank reserved for children that was balanced on the arms of the barber’s chair and scowled.

Was it then, on that strange morning at the barber’s, when this unattainable word started to fall away from us? He did what he could with the mess and in a few weeks her hair grew out and the accident was forgotten. But the dream of stylish loosened its hold on us. There would be moments in the years to come when we’d be touched by it again — the time my mother took me to a shop in town and bought me shoes with the elegant word ‘Henry’ printed on the soles, for instance, or when my sister went by herself to the right-hand neighbour’s and finally got herself that Lady Di haircut.

But on the whole we seemed to have given up the fight. I gradually stopped falling ill and falling down, lost interest in hide-and-seek, no longer took the cord of the electric kettle and sang into it like Nazia Hassan. We remained children for a little longer, still yearning for the sophistications of an adult world, till that too passed and we became, for better or worse, the people we were meant to be, no more those we hoped to become.

Related posts from Verve:

Verve Trending

Sorry. No data so far.

us on Facebook to stay updated with the latest trends